“My phone number began circulating as the situation escalated in and around Beirut,” says Shafik, a Bangladeshi community leader who has lived in Lebanon for nearly 30 years. “It was not free, but we needed anything at that point. There were hundreds of us on the streets.”

As Lebanon reels from the impacts of a fragile ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah, the humanitarian crisis for the over one million people the armed conflict displaced is far from over. Among these groups are migrant domestic workers (MDWs), who have been forced into displacement alongside Lebanese citizens and refugees.

Approximately 22,000 migrant workers were displaced and in need of shelter and support at the peak of Israel’s military escalation, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), though the full breakdown by nationality remains difficult to ascertain. These workers face a precarious reality, often finding themselves caught between the structural violence they encounter and the challenging conditions within overcrowded, under-resourced shelters.

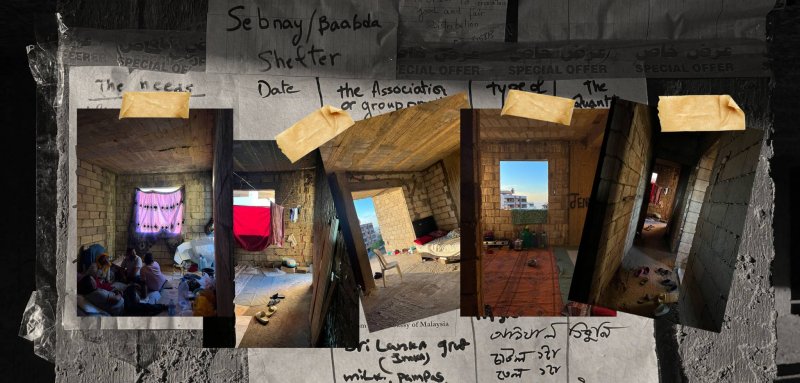

The landscape of shelters accommodating MDWs during Lebanon’s displacement crisis reflects a stark combination of systemic neglect and grassroots organizing. Informal migrant-friendly shelters emerged as critical yet under-resourced spaces amidst the chaos, with 52 such shelters identified as hosting migrants during the conflict, according to a needs assessment and mapping exercise conducted by the Institute for Migration Studies at the Lebanese American University. Since the ceasefire, 15 of these shelters have already closed, underscoring both the precariousness and fragility of these spaces and the urgent need for migrants to escape the detrimental living conditions they endured during their time there.

The Mkalles shelter currently pays approximately $500 in rent monthly, with running costs covered by community donations. There is no consistent food supply; residents pool resources to purchase food, resorting to wood-based cooking due to a lack of gas. “Our shelter provides a roof over people’s heads, yes. But the conditions here are dire,” Shafik clarifies. “Many people sheltering here could not wait to leave.”

Bangladeshis represent one of the largest migrant communities in Lebanon, ranking as the second most populous nationality among the country’s migrant population, according to the IOM and Migrant Presence Monitoring (MPM). In 2023, the MPM identified 36,145 Bangladeshi nationals residing across all 26 districts of Lebanon, although estimates place the total number of Bangladeshis in Lebanon at over 100,000. Close to half of this population are women, including girls under 18, underscoring the gendered dimensions of their migration experience.

By September 2024, an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 Bangladeshis from South Lebanon had fled to Beirut amid escalating conflict, with 3,000 displaced within Beirut as well. Many initially lived without shelter before finding temporary refuge in informal shelters or within their community networks. Detrimentally, many were reported missing, hurt, or killed.

While the Embassy of Bangladesh in Lebanon, in coordination with the IOM, has facilitated the voluntary repatriation of 151 Bangladeshi migrants of the 1,800 who expressed they wished to return, none from the Mkalles shelter have been repatriated. Residents cite a lack of adequate support from both their embassy and the IOM as the primary reason. Others cite the lengthy process of their embassy’s need to relocate as another reason for their slow response to the crisis.

Approximately 22,000 migrant workers were displaced and in need of shelter and support at the peak of Israel’s military escalation, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), though the full breakdown by nationality remains difficult to ascertain. These workers face a precarious reality, often finding themselves caught between the structural violence they encounter and the challenging conditions within overcrowded, under-resourced shelters

“We heard of many Bangladeshis receiving support to return to Bangladesh. But this was only a very small number. I am not sure how they arranged this, as no one came to our shelter to offer this,” shares a Bangladeshi woman currently residing at the shelter who requested anonymity. “In any case, many of us do not have our documents in order. We are a very big community in Lebanon. [The] small number of people that left does not make a huge difference. Our embassy could do much more.”

Despite reportedly receiving limited support—such as portable toilets and hygiene kits from ACTED and the Bangladeshi Embassy, and health checks from Médecins Sans Frontières—the shelter struggles to meet basic needs. Water access is limited to a single hose, and repairs rely on volunteers and community networks. The shelter’s leader, Shafik, is not part of IOM’s migrant working group but has connections with AMEL, which he reports provides occasional referrals.

Many migrants who attempted to return to their previous homes in Lebanon have since returned to the shelter again, discovering that their residences were either completely destroyed or remain uninhabitable. “The situation in the shelter was too challenging. Once we arrived, we found the building was severely damaged,” says Mokhtar, a Bangladeshi man who returned to the shelter from Dahieh. “The livable spaces in Dahieh are limited at the moment. Also, residents are prioritizing Lebanese displaced persons, not us. This is why we returned. Thankfully, [the shelter] is still operational, but we do not know for how long.”

The migrant-led Mkalles shelter exemplifies the resilience of displaced communities while also shedding light on the systemic failures that have left MDWs without adequate support. This vulnerability is not solely a product of the recent conflict. For years, Lebanon’s Kafala system—a labor sponsorship scheme that ties migrant workers’ legal status to their employers—has subjected domestic workers to exploitative conditions. Many endure long working hours, verbal and physical abuse, and denial of basic rights such as freedom of movement or the ability to change employers. Reporting abuse often leads to imprisonment, deportation, or further exploitation, trapping MDWs in a cycle of systemic neglect and abuse.

I am not sure how much longer we can sustain our operations. We are working on alternatives at the moment for people who are still here—perhaps disperse them to multiple smaller shelters and close this one down

Now, with the conflict subsiding, even if momentarily, many MDWs are left with few options. Initially escaping abusive employers or being rejected by shelters prioritizing Lebanese citizens, they sought refuge in informal migrant-led shelters that are neither equipped nor designed to support them adequately. As the ceasefire holds, the future of the shelter remains uncertain. Declining numbers and high running costs make its continued operation increasingly challenging, although the building owner and local authorities have not pressured residents to leave. For now, the shelter remains open, offering temporary refuge to those with no other options, particularly for individuals whose homes have been destroyed and are uninhabitable.

"There are still over 200 of us. Running a shelter as large as this one with a significant drop in people is challenging,” says Shafik, who continues to manage the mounting costs and the delegation of daily tasks. “I am not sure how much longer we can sustain our operations. We are working on alternatives at the moment for people who are still here—perhaps disperse them to multiple smaller shelters and close this one down.”

If Lebanon’s humanitarian response is to equitably address the needs of all displaced groups, it must dismantle the structures that perpetuate exclusion and exploitation. For MDWs, this means not only addressing immediate needs like shelter and safety but also enacting long-overdue reforms to systemic inequalities that have denied them dignity and rights. Until such changes occur, MDWs will remain trapped—not just by the conflicts that displace them but by the very systems that claim to protect them

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!