“Any news about your brother?”

This is what Amer Matar’s mother asked him on a daily basis after his brother was detained by ISIS for opposing their crimes and practices. Amer never imagined that his relentless search for his missing brother would inspire a project titled the ISIS Prisons Museum (IPM)—an exhibition documenting the group’s crimes in neighboring Syria and Iraq, using virtual reality and modern technologies to preserve and document its atrocities.

Amer Matar, a Syrian journalist and the founder of the ISIS Prisons Museum (IPM), stands in the middle of the exhibit hall as he speaks to visitors.

Amer Matar, a Syrian journalist and the founder of the ISIS Prisons Museum (IPM), stands in the middle of the exhibit hall as he speaks to visitors.

Amer Matar, a Syrian journalist and the founder of the ISIS Prisons Museum (IPM), stands in the middle of the exhibit hall as he speaks to visitors.

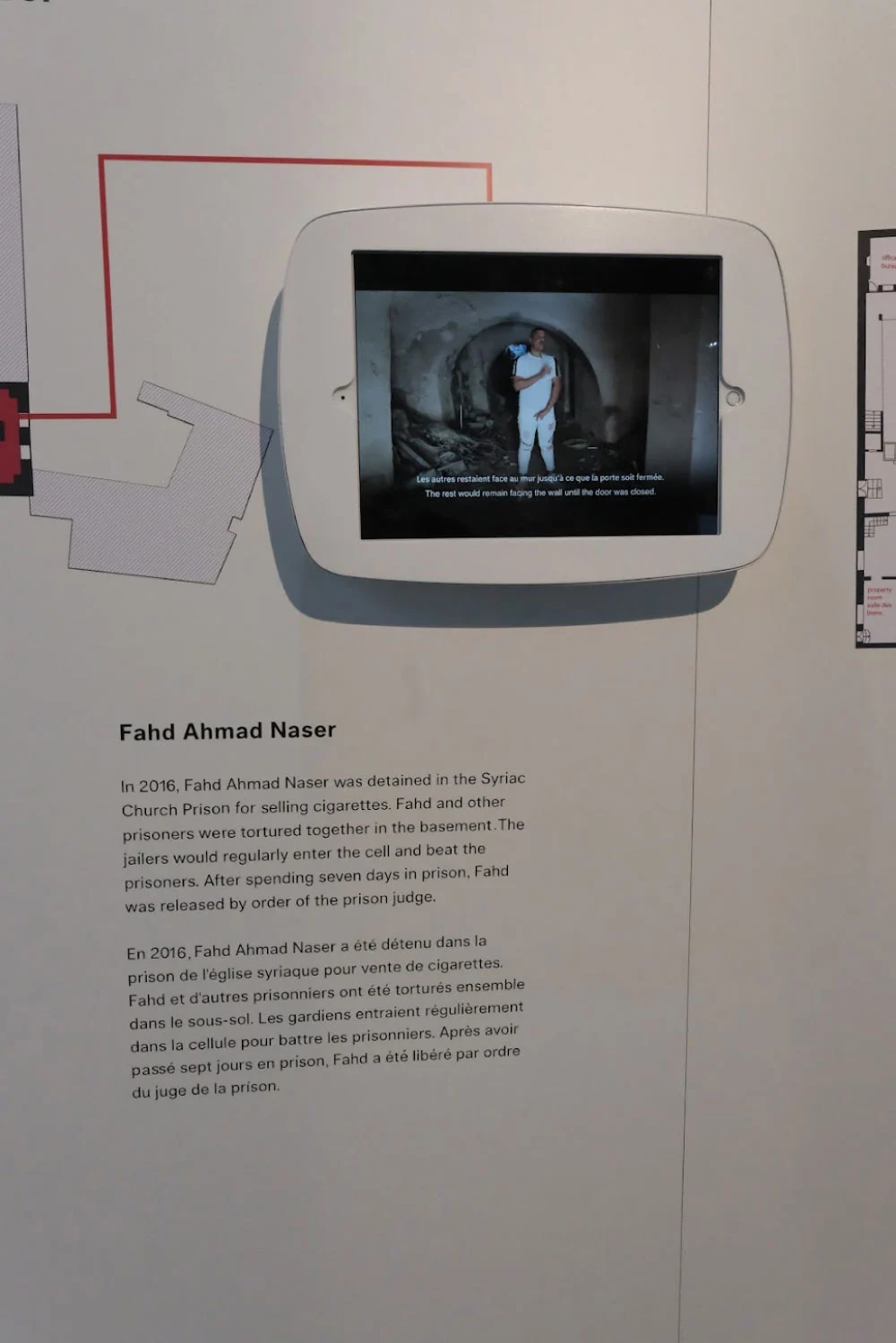

As part of the project, the digital exhibition “Three Walls: Spatial Narratives of Old Mosul” was held at the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris. Within the first few days, the exhibition attracted thousands of visitors, driven by their curiosity to understand the extent of the atrocities committed by ISIS. Using virtual reality technology, 3D tours, and VR headsets, visitors were able to witness the devastation of Mosul during its occupation by ISIS in June 2014. The exhibition also featured special screens showing recorded testimonies from former prisoners, who recounted their stories through audio and video from the very locations that once served as their prisons.

From the personal journey of searching for his brother to a monumental project documenting its crimes and victims, Matar shared his story with Raseef22 during a visit to the exhibit in Paris.

“My brother was a photojournalist,” said Matar. “ISIS arrested him while he was documenting a protest by women demanding the release of their sons and husbands from the group’s central prison in Raqqa, Syria. The second time he was arrested, he never came back. That was in 2013.

“He had been filming military movements between Free Syrian Army forces and ISIS. We immediately began searching for him in various prisons once the area was liberated from ISIS control. This gave me access to ISIS detention centers, prisons, and areas they controlled, hoping to find any clues about my brother’s whereabouts or fate.”

From the personal journey of searching for his brother, who disappeared under the extremist group’s reign, to a monumental project documenting its crimes and victims—what do we know about the ISIS Prisons Museum, which launched its first exhibition in Paris this month? And how does it offer visitors a unique, up-close, and immersive experience of ISIS’s practices and atrocities against its detainees?

Matar, his family, or friends entered, regularly encountered names written on walls and scraps of information. He also found vast quantities of abandoned documents in ISIS’s security headquarters and prisons. Some of these documents contained thousands of names of detainees, according to Matar. This discovery compelled him to take responsibility—not just to continue searching for his brother but to help other families uncover the fates of their missing loved ones.

From the exhibition at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris, Amer Matar explains to visitors the advanced technologies used in the project. Here, a smart screen allows attendees to virtually explore buildings once used by ISIS as their headquarters.

From the exhibition at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris, Amer Matar explains to visitors the advanced technologies used in the project. Here, a smart screen allows attendees to virtually explore buildings once used by ISIS as their headquarters.

From the exhibition at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris, Amer Matar explains to visitors the advanced technologies used in the project. Here, a smart screen allows attendees to virtually explore buildings once used by ISIS as their headquarters.

Matar and his team are now working on launching a platform called Jawab (Answer), integrated into the IPM website. This platform will allow anyone to search for abducted individuals, aiding families in finding information about their loved ones based on names collected during years of documentation from ISIS prisons and detention sites.

“I realized I had to handle the documents and evidence I was finding daily with extreme care and responsibility. While none of the documents mentioned my brother, they revealed the stories and clues to thousands of other missing people,” shared Matar. “This is where the story began—to compile this data into a database that could help families trace their missing loved ones.”

The team has compiled data from more than 100 ISIS prisons across Syria and Iraq. This effort was made possible with the help of over 100 professionals, including investigative journalists, photographers, legal experts, architects, artists, filmmakers, 3D design specialists, translators, and field researchers. The team also relies on testimonies from local communities to uncover the fates of the disappeared and support efforts toward justice and accountability.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

Among the evidence uncovered by the team during their documentation journey were written documents, audio and video recordings, personal belongings of former detainees and ISIS members, and computers and memory drives. The team behind the exhibition carefully digitized and cataloged these materials, organizing the information into databases, and conducting in-depth analyses.

“We entered a building in Raqqa, Syria, inspecting the prison’s features. We found writings of women's names written on the walls and drawings made by children who had been imprisoned there. The names on the walls indicated that the prison held Yazidi women, while the drawings—after days of analysis and study by the team—depicted the children’s journey from Iraq to Syria. They drew multiple cars, children, and naked men. These were the scenes the children witnessed and etched onto the walls.”

A visitor at the Paris exhibition, held at UNESCO headquarters, explores 3D-rendered buildings documented by the ISIS Prisons Museum team.

A visitor at the Paris exhibition, held at UNESCO headquarters, explores 3D-rendered buildings documented by the ISIS Prisons Museum team.

A visitor at the Paris exhibition, held at UNESCO headquarters, explores 3D-rendered buildings documented by the ISIS Prisons Museum team.

The team did not stop at documenting prisons. They also mapped mass graves, many of which were connected to the prisons or provided clues to their locations. Additionally, they documented villages and buildings that ISIS repurposed to carry out its crimes, turning them into sites of violence against civilians.

Using virtual reality technology, 3D tours, and VR headsets, visitors were able to witness the devastation of Mosul during its occupation by ISIS in June 2014. The exhibition also featured special screens showing recorded testimonies from former prisoners, who recounted their stories through audio and video from the very locations that once served as their prisons.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

A glimpse inside the ISIS Prisons Museum exhibit.

“All prisons under ISIS were repurposed buildings—family homes, hospitals, schools, or government facilities. This is why we began documenting these prisons through the use of different techniques. When we started the field documentation phase, we noticed that many of these prisons were disappearing, their features fading. Each building was a piece of evidence, with walls that held names and stories. That’s when we decided to employ full architectural scanning and 3D imaging to preserve them. That was the first phase of the project,” Matar explains.

“The second phase involved analyzing the buildings architecturally to determine how each prison and its rooms were utilized. From there, we moved to the stage of virtually rebuilding the structures as they were before the destruction. We started to understand the interior design of the homes, the layout of the houses, and how they were furnished. Mosul family homes are distinct from Syrian homes. Survivors—witnesses or former detainees of ISIS—helped us identify spaces within these buildings: where prisoners slept, the location of the interrogation room, the torture rooms, and whether there was a cabinet and even its color. We tried to gather every minor detail, as even the smallest piece of information greatly helped us in virtually reconstructing these homes."

The museum's first exhibit, which ran until Thursday, November 14, in Paris, highlighted testimonies and evidence gathered since the project's launch in 2017, focusing on three locations in Mosul: the Syriac-Catholic Church, the Great Al-Nuri Mosque, and a family home in the Meydan district of Mosul’s western side, which ISIS transformed into a detention and torture facility.

3D techniques were used to create an immersive, realistic experience for exhibition visitors.

3D techniques were used to create an immersive, realistic experience for exhibition visitors.

3D techniques were used to create an immersive, realistic experience for exhibition visitors.

3D techniques were used to create an immersive, realistic experience for exhibition visitors.

3D techniques were used to create an immersive, realistic experience for exhibition visitors.

From hundreds of stories, evidence, and eyewitness accounts, along with the findings of Matar and his team during their documentation journey, one incident left a lasting impact.

“We entered a building in Raqqa, Syria, inspecting the prison’s features—the doors, windows, and items inside. We found writings of women's names written on the walls, which was not unusual in many buildings we visited. But in this particular place, the most shocking discovery was drawings made by children who had been imprisoned there,” Matar recounted to Raseef22, standing inside the exhibition hall. “The names on the walls indicated that the prison held Yazidi women, while the drawings—after days of analysis and study by the team—depicted the children’s journey from Iraq to Syria. They drew multiple cars, children, and naked men. These were the scenes the children witnessed and etched onto the walls.”

Amro Khaito, a co-collaborator of the IPM project, told Raseef22 that “the differences between the cities of Raqqa in Syria and Mosul in Iraq, both under ISIS control, led our team to expand our documentation efforts from Mosul into Syria. Each city has unique characteristics, and ISIS’s management of prisons in Mosul differed in certain ways from how it operated in Raqqa.

“Our main drive and motivation in this project is to document a dark period that passed in the lives of people in Iraq and Syria. I believe this is incredibly important for UNESCO in preserving the archive of human memory and the black chapters of history that form part of that memory."

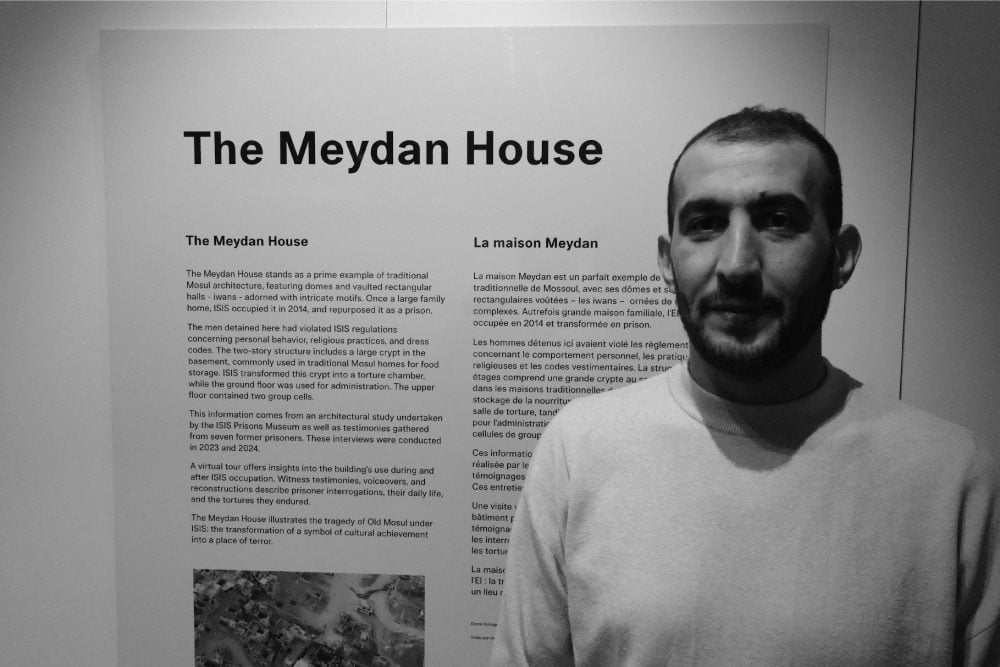

The events documented by the museum’s team depict ISIS’s actions in areas under its control. Khaito emphasizes that “ISIS was not some monster that descended from the sky and swallowed the region and its people. It was a structure with numerous intricacies and layers that allowed it to dominate these areas. By highlighting a prison in the Meydan neighborhood—originally a home of a Mosul family—the symbolism becomes evident. ISIS intentionally turned 'homes' into instruments of threat, where any house could be transformed into a prison, whether by ISIS or other groups. This became a chilling possibility. When prisons overflowed, ISIS would construct ceilings for the prison or balconies in the homes they had converted into prisons, demonstrating how easily such prisons were created, reflecting their overarching oppression and control over our lives.”

The IPM team is preparing to showcase the exhibition in multiple cities as part of a tour aimed at raising awareness about what happened in Mosul and Raqqa under ISIS’s control. Upcoming exhibitions have already been announced for Berlin and London, with additional cities to be revealed later.

“One of the biggest challenges we faced was the fear associated with mentioning ISIS. Just saying the name made people want to avoid the subject entirely,” added Khaito. “It was a major challenge to present this exhibition in a venue that embodies culture, science, and human memory. But we felt that UNESCO headquarters perfectly suited the project’s purpose.”

Amro Khaito, co-founder of the IPM project, stands in front of a wall displaying information about a house that ISIS converted into a prison.

Amro Khaito, co-founder of the IPM project, stands in front of a wall displaying information about a house that ISIS converted into a prison.

Amro Khaito, co-founder of the IPM project, stands in front of a wall displaying information about a house that ISIS converted into a prison.

* All photos in this report were taken by Azhar Al-Rubaie

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!