In 2014, the extremist jihadist group ISIS shocked much of the world after taking over large swathes of land in Iraq and Syria and declaring a caliphate. With roots stretching back to the US occupation of Iraq, ISIS went from relative obscurity in the public eye to a group appearing to command the West's attention—and policy platforms. After all, ISIS at that time seemed unexpectedly capable of accomplishing serious harm to the West and its interests. The group, which quickly became infamous for its brand of extreme brutality and willingness to commit cultural atrocities, at one point controlled around 8 million people; dominated a combined landmass nearly the size of Cuba; and generated billions of dollars in revenue from oil, taxes, and extortion.

Before its eventual downfall, the group seemed fairly well organized, too. The group presented itself as a political-religious state, had meticulous record-keeping and tax schemes, used moderately advanced weapons it stole from Russian and US defense transfers, and inspired thousands of foreign fighters to join its cause. Moreover, ISIS was claiming high-casualty attacks in the West in France and Germany.

With the rapid rise of ISIS came an equally powerful wave of articles, speeches, debates, and op-eds dissecting the group with a certain flair of naïve intrigue that would make Edward Said roll over in his grave. Attention-seeking writers pondered why “they” hate “us” (as if the prior twenty years of American foreign policy existed in a vacuum), prominent writers wondered what the group really wanted, and US presidential hopefuls had official campaign policies on ISIS and publicly debated it in the leadup to the 2016 general election. Even Bernie Sanders, the anti-war US Senator known for being one of the few American politicians who voted against invading Iraq, had a section on his 2016 presidential campaign website about containing ISIS. The American public began to grow concerned, too.

I distinctly remember a classmate of mine pulling me aside in my school’s library in the Fall of 2015 and, after telling me about the urgency of defeating ISIS, pointedly asking me: “Well, what do you think about the threat of ISIS”?

A 2017 Pew Research poll found that nearly two-thirds of Americans found ISIS to be the top threat facing national security, beating out climate change, China, and Russia. Another 2017 Pew Research poll surveyed 10 EU countries and uncovered that a median of 79 percent of surveyed Europeans were concerned about Islamic extremism. Thousands of miles away in my public high school in Montana, my classmates were also worried. In a small American city of less than 100,000 people, my peers were asking each other what the United States should do about the fear-mongering group. I distinctly remember a classmate of mine pulling me aside in my school’s library in the Fall of 2015 and, after telling me about the urgency of defeating ISIS, pointedly asking me: “Well, what do you think about the threat of ISIS”?

It seemed like ISIS, regardless of its true capabilities, had dominated our political imagination.

From top of mind to apparent defeat

However, the group’s centralized power and pseudo-state form failed to last long. Nearly as quickly as the militant Salafist group declared statehood, the United States and its various allies in Europe and the Middle East unveiled the 83-member Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. ISIS began facing multiple fronts of warfare between US-backed Kurdish forces, Russia-backed pro-Assad forces, and Iraqi forces. By 2017, the United States launched nearly 25,000 air strikes (around 23 a day) and spent at least $14.3 billion on the fight against ISIS.

Increasing gains by local fighters and the coalition’s increasingly active bombing campaign—one that reportedly led to the deaths of thousands of Syrian civilians—led ISIS to rapidly lose ground. Coalition-backed forces liberated all major ISIS-controlled territories by early 2019, and on October 26, 2019, ISIS’s infamous leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi blew himself up with an explosive vest as American forces surrounded him in northwestern Syria.

By 2020, the number of victims ISIS killed in terrorist attacks in Iraq and Syria had dropped dramatically.

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

Estimates surrounding the yearly number of ISIS-claimed deaths in Iraq and Syria compared with the growing and falling amount of territory the group controlled from 2013 to 2018. (Source: Statista)

The number of deaths from terrorism in Iraq and Syria. Despite a large spike during the US invasion of Iraq and the rise of ISIS, deaths from terrorism in both countries have steeply declined. (Source: Global Terrorism Database)

It is important to note that ISIS has continued to claim terrorist attacks in the West or in areas affecting Western interests (the most devastating terrorist attack in 2021, for example, was an ISIS attack on Hamid Karzai International Airport during the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, which killed 11 Americans). However, terrorist attacks affecting Europe and the US have in general steeply declined.

Confirmed yearly deaths by terrorism across the regions associated with the “West.” Despite a spike during the height of ISIS activity in the mid-2010s, deaths from terrorism have definitively trended downward in these regions. (Source: Global Terrorism Database)

The Fall of ISIS…and Western interest in it

Concurrently, as ISIS lost virtually all the territory it controlled in the Levant, it was also losing its grip on the public’s interest in the West. In 2019, Pew Research found that Americans were worried about ISIS 12 percent less than in 2017, and a median of 68 percent of surveyed Europeans were worried about the group/Islamic extremism—11 percent less than in 2017.

In stark contrast to opinion polls five years earlier, a 2022 Gallup study found that jihadist terrorism/ISIS failed to even make the cut into the top fourteen issues Americans found to be affecting the country. A general trend of gradual Western disinterest in the group can also be found in Google search data.

The relative interest of US-based Google users in “ISIS” since 2004. Google-based interest in the group peaked in November 2015. This trend largely remains replicable for users in other major Western countries, such as Australia, France, Germany, and Spain. (Source: Google Trends)

According to trend statistics from Google, American interest in ISIS peaked in and around 2015; soon thereafter, Americans’ interest in the group exponentially declined and has stayed flat.

The availability heuristic (also known as availability bias)—a psychological phenomenon that highlights how when things are shown more often in the media, they seem more common—may help explain this decline in interest. Terrorism—and terrorism committed by Muslims—appears to get a far greater share of Western news coverage than other topics.

According to an aggregate study of The New York Times and The Guardian coverage of what Americans die from, terrorism was overrepresented in Western news outlets by nearly 4,000 times in 2016. Moreover, a 2019 study found that major media outlets such as CNN covered terrorism 758 percent more often when the perpetrator was a Muslim. The more attacks Western policymakers and voters saw in places that felt familiar, the more the threat of ISIS felt like a real and present danger.

Over the past thirty years, after major terrorist attacks in Europe and the US occurred, American fears about terrorism spiked (even though an average of 0.006% of American deaths from 1996 to 2017 were attributed to terrorism). As the theory goes, as ISIS lost territory and power and the West saw fewer depictions of terrorism, Westerners cared less about the group. Whatever the cause, the data suggests that audiences in the West are decreasingly interested in ISIS.

Experts have raised questions about whether Western governments understand—or care about—ISIS as it expands outside of the Middle East. It's critical to acknowledge the harm ISIS is causing—and the group’s expansionist desires. So, what does ISIS really want?

Indeed, a casual observer might assume that with the downfall of ISIS, the general decline in high-casualty terrorist attacks affecting the West, the West’s decreasing public interest in the group, and the United States’ gradual troop withdrawal from the region, the West has largely adjusted its priorities. But has ISIS moved on? Not exactly.

ISIS in 2023: A Trend toward Africa, Central Asia, and Decentralization

I spoke with counterterrorism expert and Baghdad native Farah A., who requested that her full name not be revealed for security reasons, to better understand ISIS’s recent history and how the group, and its image, changed over time.

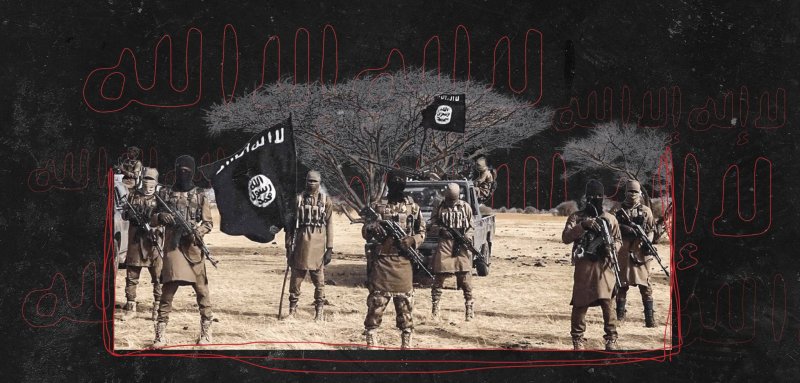

ISIS initially “gave the illusion that it was very strong and powerful,” declaring that it was “a complete state with leadership and [government] branches, and [capable] of conducting business … and [running] health and educational systems.” The careful image ISIS cultivated with its highly refined propaganda machine helped depict an organization that “motivated many foreign actors, or lone wolves, to act in ISIS’s name… It was a shock to the world.” ISIS, Farah noted, presented itself as a centralized state commanded by organized leadership in Iraq and Syria.

However, as the group faced collapse in 2019, it transitioned into a more decentralized organization, with much of its leadership now in hiding and chapters spread across Sub-Suharan Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, ultimately united by the group’s signature propaganda machine.

ISIS presented itself as a centralized state commanded by organized leadership in Iraq and Syria. However, as the group faced collapse in 2019, it transitioned into a more decentralized organization, united by the group’s signature propaganda machine

As Farah highlights, from a propaganda perspective, ISIS has remained highly prolific. Official ISIS accounts and groups supporting ISIS online still share claims of responsibility for attacks on targets in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Syria. Despite the group’s diminished activity in the West, ISIS propaganda attempts to give the illusion that the group’s statehood is still present, that the group acts as one, and that actions on the ground are successful.

Furthermore, while the group’s structure was changed by force in a dramatic way, it is not necessarily weaker; it is functioning differently. After all, although ISIS-claimed casualties and attacks were down in both Iraq in Syria in 2022 compared to 2021 and the group has faced a series of major challenges (the US-led coalition against ISIS killed two new self-proclaimed caliphs of ISIS and at least six additional senior officials in 2022 alone), the group is still relatively active.

ISIS is proving notoriously tough to contain in Syria and Afghanistan and has vowed to liberate some 10,000 imprisoned ISIS militants in northeast Syria. Despite the overall trend downward in the frequency of terrorist attacks, ISIS still launched multiple attacks per month in Iraq, Syria, and the Sinai in 2022. Moreover, the group’s provinces in Africa and parts of Asia are increasingly active. According to the group’s claims, the group also appears to have shifted to launching more attacks in Africa than elsewhere.

The deaths from terrorism across the world. Although deaths from terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa have declined, they have increased in parts of Asia and Africa. (Source: Global Terrorism Database)

Facing an increasingly difficult status quo, ISIS’s smaller chapters—whether that’s in the group’s Central Africa Province or Khorasan Province in Afghanistan and Pakistan—are launching attacks in their own regions, with or without guidance from central ISIS leadership. Farah expects the group’s more decentralized structure to largely stay the same for the foreseeable future.

Looking forward, one thing to take note of, Farah urged, is that although ISIS looks much different now than it did in 2015, it is very capable of wreaking havoc on the communities it still exerts its influence on. “The group’s presence still practically presents a danger in the areas it is active in, [presenting] a poignant fear for those in the region.” Moreover, “we shouldn’t assume that they are diminished entirely… [just] because the West doesn’t fear, doesn’t mean other areas don’t.”

While she assesses that the US and its regional allies will make it hard for central ISIS to identify future leaders for the group, she also noted the importance of keeping up the fight against one of the group’s most potent recruitment tools: ideology. Even though the group offers fighters varying degrees of economic security and social benefits, ideology represents a major recruitment tool, as represented by the group’s ability to recruit thousands of members largely over social media. “Unless governments use active measures to educate people on what true Islam is and how to practice faith from a holistic perspective, the threat of ISIS can not be tackled effectively.”

From a propaganda perspective, ISIS has remained highly prolific. Despite its diminished activity, ISIS propaganda attempts to give the illusion that ISIS’s statehood is still present, that the group acts as one, and that actions on the ground are successful

ISIS is effectively expanding in areas where Western powers have less influence (and interests), such as Sub-Suharan Africa and the now Taliban-run Afghanistan. This raises questions about whether Western governments understand—or care about—the group as it expands outside of the Middle East. Even though the West may not like it, it is critical to acknowledge the serious harm ISIS is causing in other regions—and the group’s expansionist desires.

So, what does ISIS really want? For us to ask better questions. To not ask why “they” hate “us” or whether another bombing run on ISIS will do the trick, but about the people ISIS still violently controls, or about why the West seemed to stop caring as ISIS targeted it less and less.

While the West may have moved on from ISIS, it is important to remember that millions of people in Iraq, Syria, and various countries in Africa are not so easily able to forget the group. For them, attacks, kidnappings, burnings, and other atrocities are a poignant symbol not only of ongoing existential threats to their existence, but that the West has better things to worry about.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!