I happen to have a fantastic husband. I met him in 2018 on a summer day, after having my heart torn apart.

As I wrote a post in a Facebook group dedicated to Middle East and North African music, his name popped up. He offered to meet and play some music together. We met in a small café in a small linden-lined street in Berlin. According to him, I was quite late. Since then, every day, I look at him and feel extremely lucky.

First, I have a husband who grew up in streets paved with thousand-year-old stones covered in jasmine. When he used to go home after partying on the weekend, he loved leaning against the great Umayyad mosque to rest for a couple of minutes at night. I picture a young him walking under the stars of Syria, his lean silhouette moving in the narrow streets of Bilad aa-Sham, just like his Palestinian parents and grandparents before him.

In his veins run thousands of years of history and culture. When he was not hiking in the backcountry of Latakia, he used to drive on the roads of Syria to visit its cities and villages. One of his biggest regrets is that he didn’t have the time to see Aleppo, as he had to flee the violent repression imposed by the Assad regime on a youth dreaming of social justice, freedom, and dignity. My husband already had a flamenco band in those days. As a musician, he also played the Don Juan. He had a soft spot for cats, just like me, and he continues until today to speak of the first one he owned in his house in al-Yarmouk, a white fluffy and cuddly cat named “Rommana,” pomegranate, in Arabic.

In his veins run thousands of years of history and culture. When he was not hiking in the backcountry of Latakia, he used to drive on the roads of Syria to visit its cities and villages. One of his biggest regrets is that he didn’t have the time to see Aleppo, as he had to flee the violent repression imposed by the Assad regime on a youth dreaming of social justice, freedom, and dignity.

I have a husband who supposedly comes from different shores. As a French European who happens to be a Mediterranean as well, I don’t see them as so distant or foreign. He grew up on the other side of our magnificent sea, where I also used to swim with my parents when I was little. The only difference is that I had the chance to go there more often than he did, son of Bilad aa-Sham. The eternal romantic that I am often wonders if he also bathed there the same day as I was watching the ferries leave the port of Bastia in Corsica every summer. However, since I know him very well, I rather picture him running around screaming at the seagulls than calmly watching the horizon of a sea that would become a mass grave one day.

I now share my days with a kind human being, with a great sense of humor and a fine dose of self-derision, which allows me to talk to him about absolutely everything. Someone gentle and sensitive, with a strong sense of duty, who deeply cares about our families. He doesn't hesitate to learn crochet to help me knit a jacket or dry flowers with me in the parks. I admire his patience as I see him waiting for me while I am once again filming birds on our way to pretty much anywhere. We live in Berlin, and in the evening, he comes to pick me up from the library, just to spend time with me and chat on our way home. Sometimes, we stop for sushi, and we laugh, while he desperately tries to get a hold of the chopsticks. He is my partner and companion, the one who is the closest to my heart, and who sees all of me as I stand by him.

The author's husband on a hike in France.

The author's husband on a hike in France.

My husband hikes in France. (Image by Elise Daniaud Oudeh)

As my husband had to leave his country against his will, I have tried to create a welcoming home he could reclaim—something his family was unjustly deprived of twice. I have been thrifting vintage objects coming from Syria and Palestine in Europe, such as two boxes and a picture frame in traditional marquetry and stamped table linen. For our wedding, I asked a friend to bring us dry jasmine from Damascus, which we framed on a poster with pictures of the ancient city. In a fair world, we would have gotten married twice, once in France and once in Syria, and taken our wedding pictures in front of the fountain of a Damascene patio. The Syrian regime decided otherwise. My husband often jokingly asks me if our house is an annex of the Louvre. I personally wouldn’t mind. My husband also loves my family as much as my family loves him. My father, bless his soul, used to call him his second son. He also managed to come closer to my mother and her strong independent character. My eighty-four-year-old uncle and eighty-eight-year-old aunt directly adopted him as a member of our family, followed by my cousins. Reciprocally, I also love his mother and siblings with all my heart and always felt welcomed and accepted by them. I wish all married couples to be granted such harmony.

Why do I suddenly feel the urge to draw a very intimate picture of him, a discreet and humble man who does not like too much attention? And why do all these small details I’m writing about now come to my mind? The reason is that this very happy little French-Syrian-Palestinian cocoon rooted at the crossroads of Mediterranean histories has not escaped the crushing pressure of German society since October 7.

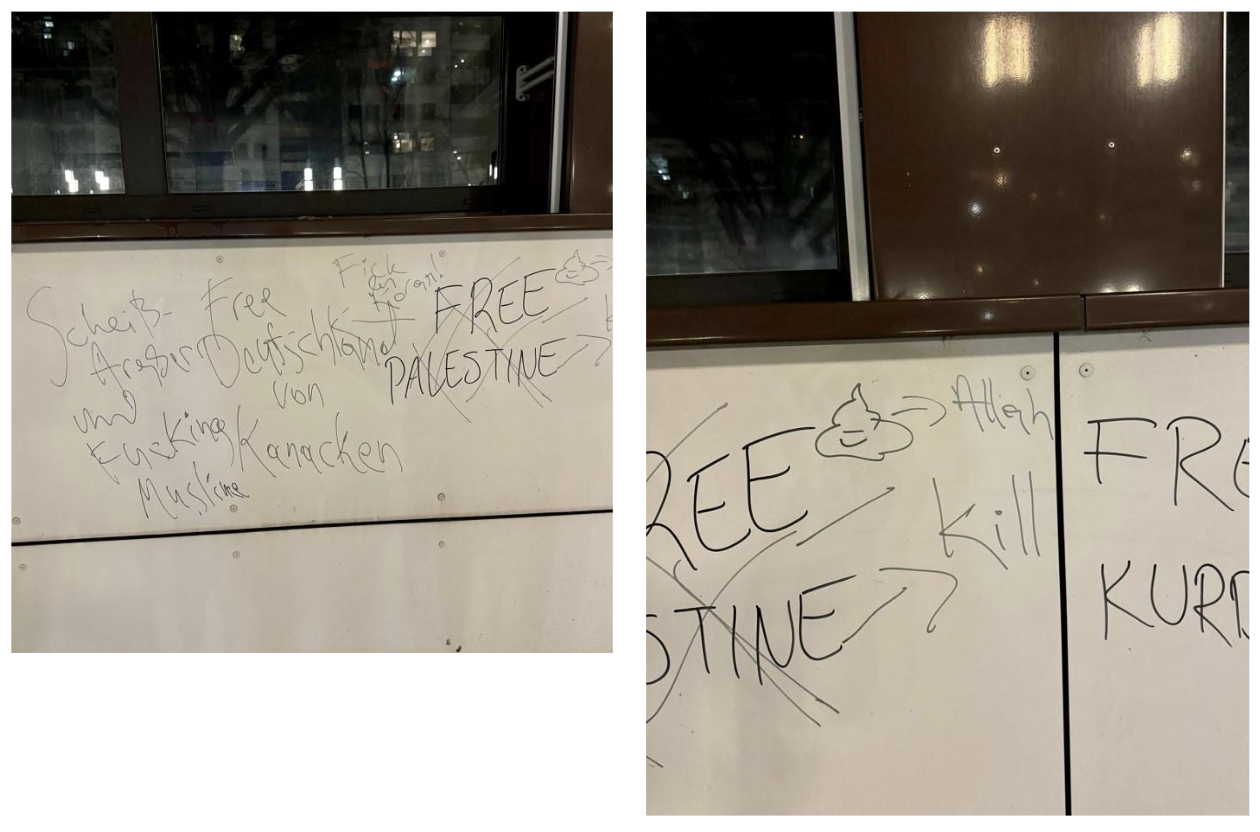

Day by day, as we try to cope with the horrendous news and heart-breaking images coming from Gaza, I am also overwhelmed by a tangible sensation of systematic hostility that crushes everything in its path. No, our bubble did not escape the looks when we spoke Arabic, the microaggressions in the public spaces, the racist graffiti in our street of Charlottenburg, and all sorts of unsolicited questions and comments—so many symptoms of the latent animosity that later fully exploded in the German society. My husband does not escape the fear and anxiety either, and I cannot make his days sweeter.

No, our bubble did not escape the looks when we spoke Arabic, the microaggressions in the public spaces, the racist graffiti in our street of Charlottenburg, and all sorts of unsolicited questions and comments—so many symptoms of the latent animosity that later fully exploded in the German society. My husband does not escape the fear and anxiety either, and I cannot make his days sweeter.

The author photographed racist graffiti in Berlin.

The author photographed racist graffiti in Berlin.

Racist and Islamophobic graffiti in our street in Berlin, autumn 2023. (Images by Elise Daniaud Oudeh)

All these tiny events are just the tip of a big and ugly iceberg. It is a desperate attempt to hold the Arab world unconditionally and exclusively responsible for the centuries-old antisemitic history of violence rooted in Europe. It is a convenient position in hopes of avoiding some highly needed soul-searching, with Germany turning its back on the immense threat that a growing extreme right is posing to the country.

It is a desperate attempt to hold the Arab world unconditionally and exclusively responsible for the centuries-old antisemitic history of violence rooted in Europe. It is a convenient position in hopes of avoiding some highly needed soul-searching, with Germany turning its back on the immense threat that a growing extreme right is posing to the country.

Indeed, the audacity characterizing the local public discourse since October also resonates with me differently. I am an academic who chose to dedicate her career to Syria and who believes in human dignity, freedom of speech, and social justice. I am also a wife, a daughter, and a granddaughter. Like all of us French, I grew up immersed in stories about the second world war. My family suffered from German imperialism and Nazism. As my great-uncle died in his twenties in a German concentration camp after risking his life to join the resistance, my family spent considerable amounts of money trying to save a son who already died alone, far from his family, for standing up against barbarism. As my mother’s side left everything to move to the South, terrorized by the Nazis, my father’s cousins were deported to Germany as part of a forced working force, which led one to die at barely thirty.

The generation before was not spared either: after being whipped on her face at the age of thirteen by a German soldier parading with his regiment in the streets of Belgium during World War I, my great-grandmother moved to France as soon as she could. She never returned. I know about the ration coupons that this same great-grandmother later received. I know about the trauma, the fear, and the impossible mourning of a young son who never reappeared.

As a French citizen, my knowledge of Germany was also mediated by my schooling, where I was taught that our Eastern neighbor was now working on its past to get rid of its toxic supremacy and to never be an oppressor again. In high school, I watched films and documentaries that left me horrified for a lifetime, including “From Nuremberg to Nuremberg,” “Night and Fog,” “Life is Beautiful,” “Schindler’s List,” and “Sophie’s Choice.” At home, my father slept all his life with a copy of the book “If This is a Man” on his bedside table and would get into a rage if he heard any antisemitic comment from the French extreme right. Like many French families, the atrocities of the past were always very present in our daily lives.

As a teenager and a young woman, I learned about the bilateral initiatives aiming to bring our two countries together so that a third world war and genocide would never shatter our lives again, and I believed in it. And yet, here I stand today, feeling betrayed, as I sit and watch the horrendous instrumentalization of the 7 of October and its aftermath, through a broad set of unapologetically racist and anti-migrant discourses in the country deploying themselves month after month. During these painful days, the CDU leader Friedrich Merz barely waited two weeks to get the ball of shame rolling. According to him, “Germany cannot accept even more refugees. We have enough antisemitic young men in the country. We can’t kill millions of Jews and bring millions of their worst enemies in the country.” Words that left us all in shock and anger.

I feel betrayed by the conscious erasing of centuries of peaceful cohabitation and diversity in the Middle East to draw a racist caricature of the Arab world. I feel betrayed by the occultation of the socio-cultural and economic contribution of refugees to Germany, a country that made us, humanists, proud over the last decade. I feel betrayed by German politicians stirring oil on the fire to boast about themselves and actively supporting ethnic cleansing when we were promised that we would never see such days again. And I feel deeply offended by the attitude of a country that does not hesitate to lecture the world about antisemitism, pluralism, democracy, and human rights, despite its active participation in the destruction of Europe twice, in the genocide of the Jews, but also in the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia. I am also furious when I look at the German press, where I find the same discourse cheerfully taken up in unison by journalists becoming the guardians of the “reason of state” while betraying professional ethics.

In parallel, I watch my husband trying to navigate a storm that has battered European political representatives since October by awakening old demons and resuscitating the ghosts of a shameful past that they would rather forget. I watch him read the news, go to work, and try to keep steady on his feet and to keep a balance. I watch him hide his identity out of fear, shrink himself as much as possible, and anxiously read about the growing power of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) organizing a second Wannsee conference in all impunity.

Indeed, the simple existence of my other half, his status as a “Palestinian,” he who asked for nothing except for basic rights and safety, earns him endless mistreatment, especially if we add his identity as a “Muslim,” “refugee,” and “Arab.”

Indeed, the simple existence of my other half, his status as a “Palestinian,” he who asked for nothing except for basic rights and safety, earns him endless mistreatment, especially if we add his identity as a “Muslim,” “refugee,” and “Arab.” Bad treatment that many around us in Germany, I dare to hope, consider to be “regrettable” or “unfortunate,” but which does not revolt them either. Their supposable commitment to human rights and humanism does not bring them to pick up their phone and send us a message, ask us how we are doing, and invite us for a cup of tea. A state of passivity that scares me: which level of systemic violence will it take for them to stand up?

As we stand alone, I listen to my husband’s many questions addressed to the European that I am. Where is the Western pluralism and democracy? Why is he being blamed for crimes he did not commit? What did he do to be hated here? Can his existence be safe in this world? Do I believe that we will have to move again for him to have the simple right to live a dignified life? To where? Where will he finally be accepted? Will his simple existence always be considered the proof of a crime which has already lasted for seventy years, and which must be erased from memories in the East and the West?

The author's husband wears a shirt embroidered with Palestinian Bethlehem moons shaped like a watermelon, embroidered by her.

The author's husband wears a shirt embroidered with Palestinian Bethlehem moons shaped like a watermelon, embroidered by her.

My husband wears a shirt embroidered with Palestinian Bethlehem moons shaped like a watermelon, embroidered by me. (Image by Elise Daniaud Oudeh)

I do not find the right words to answer, doubled by my disillusion regarding a Europe I believed in, as I watch the city hall of Berlin not only describing the 1948 Nakba as a “myth,” but also violently silencing Israelis and Jews who do not comply with the only acceptable narrative in Germany, that is standing unapologetically with Benjamin Netanyahu’s government. I didn’t know what to tell him either when I learned that after attending the 2024 Berlinale, Germany’s minister of culture only clapped for the Israeli filmmaker of the Israeli Palestinian duo who together won the festival’s best documentary prize. Their joint film, No Other Land, treats the destruction of Palestinian villages in the West Bank. Nine months and a minimum of 40,000 deaths later, political representatives have not blinked once, or shown an ounce of remorse. On the contrary, weapons shipments continue.

In such a context, Palestinians, Syrians, and Palestinians from Syria had no time to develop post-traumatic stress disorder. To do so, they would need to be able to escape trauma, even for five minutes. Meanwhile, since October 2023, they have been facing wave after wave of trauma. Scores of police trucks patrolling Arab neighborhoods. Berlin police place water cannons in front of family restaurants. Sirens. Leaflets are distributed in schools of mixed areas. Calumnies target the Arab Muslim community in the press. Berlin bans wearing the traditional keffiyeh. German police ban demonstrations and silent vigils. The police erase solidarity graffiti. The black boots of the police crush candles in memory of slain Palestinians. Police regularly arrest Jewish, Israeli, and Palestinian activists. Police commit acute acts of violence. Literary prizes, university conferences, employment contracts, cultural residencies, artistic performances, and scholarships are canceled when activists show solidarity. Berlin cut funding to a culture center for its Palestinian solidarity stances, leading it to close. Concerts are being canceled. A music venue interrupts a set by a DJ wearing an Arabic-written t-shirt. A German state bank froze the account of Jewish Voice for Just Peace in the Middle East while demanding the personal addresses of its members. Academic centers dismiss professors. German police suppress a Palestinian solidarity congress. Germany bans a Palestinian doctor from entering the Schengen zone. Berlin criminalizes the slogan “from the river to the sea.” Berlin bans Irish-language pro-Palestine singing at protests. German police violently evacuate an activist camp in front of the Bundestag. German politicians make openly racist and Islamophobic political statements. The German government instrumentalizes politics. The press features incitement to violence and calumnies. Constant discrimination and hostility increase in the public space. New discriminatory laws take hold.

And yet, despite this, I believe that my husband deserves the best and I stand determined to offer him as much. My moral compass also makes me stand up for his rights while he can rest and lay on me. Just like I stand for Syrians, I will keep standing for Palestinians.

The author and her mother-in-law face the Atlantic Ocean.

The author and her mother-in-law face the Atlantic Ocean.

My mother and my mother-in-law face the Atlantic Ocean. This was my mother-in-law’s first holiday trip. (Image by Elise Daniaud Oudeh)

And yet, despite this, I believe that my husband deserves the best and I stand determined to offer him as much. My moral compass also makes me stand up for his rights while he can rest and lay on me. Just like I stand for Syrians, I will keep standing for Palestinians. What do people aspire to? A quiet life, a cozy apartment with a balcony full of plants, a purring black and white cat, faithful friends, a safe family, children who can fully embrace who they are, holidays at the beach, chocolate cakes, and lots of music to heal the heart. And a small but vigorous potted jasmine, in a corner, next to an olive tree, to never forget.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!