We live in a state of constant anticipation, anxiety and fear. How can we not be on edge, helpless in front of our television screens, as we watch body parts and our homeland being torn apart?

My friends describe feeling bound and powerless. For weeks, they have been glued to their phone screens, unable to engage in daily activities. Some of them are monitoring their friends in Gaza, making sure they’re still alive, while others are sharing the grim reality of the atrocities.

How can we not experience such emotion, when most of us have lived through a number of wars in close succession, in our neighboring and interconnected countries?

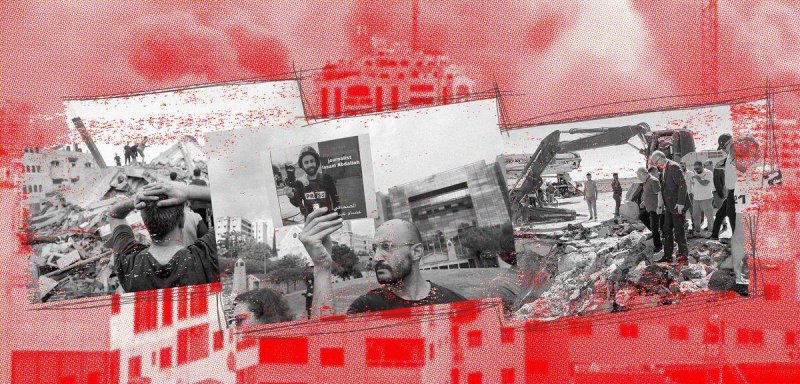

In Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, we share the same fears. Since the war began in Gaza, my memory transports me to all the wars and violence I witnessed from 2000-2006 living in South Lebanon. I recall disjointed scenes of war, some images appear in black and white, whereas in others, I can almost smell the gunpowder and hear the sounds of shelling.

In Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, we share the same fears. My memory transports me to the wars I witnessed living in South Lebanon from 2000-2006. Some memories are in black and white, whereas in others, I smell the gunpowder and hear the sounds of shelling.

The buzzing of the drone, ‘Em Kamel’, as we refer to it here, brings back memories of fear, shelling, the sounds of men outside lighting their cigarettes while the women, glued to their television screens, embrace the children. And the tea cups that didn't survive the war, after I broke them while running to my mother to escape the sound of shelling.

These are the memories stored in our minds. We have been sentenced to grow up in anticipation of shells and missiles.

An attachment to toys

I remember meeting a girl from Syria who burst into tears at the mention of the war in her country. She explained that she tried hard not to remember what she went through. But what struck me the most, was when she spoke of the toy she had to leave behind, despite being unable to sleep without it. Perhaps I didn't press further because I too had been terrified of leaving my toys behind during the July 2006 war in Lebanon. I was not only scared of leaving my toys behind, I feared losing my childhood.

Dr. Mohammed Al-Salehi, a psychiatrist and writer, sheds light on children's attachment to objects, referencing Donald Winnicott’s transitional object theory. He explains, “According to this theory, children naturally form attachments to their caregivers, typically their parents, as part of their psychological development. But when the caregiver is absent, like when he leaves the house, travels, or if he passes away, some children, in an effort to alleviate fear and reduce anxiety, create an attachment to a specific object, often a blanket, a soft pillow, or a toy.”

For Ahmad Abdulla Yahya, what remains from the 2006 war in Lebanon is the trauma of displacement, “We had to leave our home and land to escape the shelling. This caused great humiliation. Many of us who were displaced began to wish for death.”

Psychoanalyst and psychologist Naamat Bejjani stresses the importance of toys as essential tools for children that provide joy, fun, and a sense of security. Toys can also symbolize a connection to the parental figure. Bejjani explains, “During times of war, considered to be some of the most challenging experiences involving division, disarray, and existential anxiety due to separation, a child's fear and apprehension increases, which amplifies his or her attachment to a source of safety and affection. This can manifests strongly in the child becoming attached to their toys, first, to safeguard the 'doll's health and life' from any harm or adversity, second, to derive a sense of security from it in the face of the unknown, and third, to align with their parents’ feelings and growing concerns for their safety.”

Emotionally numb

Ahmad Abdullah Yahya, a resident of the southern Lebanese town Kfarchouba, which has witnessed numerous wars and Israeli attacks, questions why scenes of death and destruction no longer faze him. In a social media post, Yahya asked, “Where did the numbness come from? I remember living through 2011, witnessing the war in Syria, growing up watching children dying, being shelled or suffocated. I grew up witnessing torture, murder, and displacement. I lived among people who died frozen cold... or starving.”

Yahya emphasized that a person is human, regardless of his name, or of who killed him, and that humanity is indivisible. “As for the sound of shelling, I don't know. I was raised on the sounds of missiles and war, and even though I now live abroad, I feel like I should be in the place where I grew up – in my village and on my land.” Yaahya points out that what lingers most from the 2006 war is the trauma of displacement, “which was more difficult than surviving the bombardment and death. The idea of displacement, where we had to leave our home, land, and everything in our lives to escape the shelling and war, is akin to the sensation of death, and causes great humiliation. Many of us who were displaced began to wish for death.”

Why are we numb to this war, despite our solidarity and shared pain with Gaza? “Events accompanied by strong emotions, whether joy or sorrow, linger in our memories. And in our countries, it is the tragic memories and negative emotions that stand out.”

He adds that “events accompanied by strong emotions, whether joy or sorrow, tend to linger in our memories. Unfortunately, in our country, it is the tragic memories and negative emotions that stand out.”

What causes this numbness, despite sharing in pain and feeling solidarity with Gaza?

Dr. Al-Salehi explains, “Some individuals may be affected by what is commonly known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), especially those not accustomed to such scenes, or more sensitive individuals. Symptoms of PTSD include heightened alertness or being ‘on edge’ much of the time, disturbing nightmares relating to the traumatic event, sudden flashbacks or vividly seeing it in their mind. These things can greatly affect daily life.”

According to him, repetition leads to desensitization, “which is the same tactic we use in treating phobias. The principle of desensitization is that repeated exposure to an event or an external stimulus reduces our response to it. Over time, the response diminishes, and this is what I call emotional numbness.”

Abdul Hakeem has decided to remain in his partially bombed house, with no water or electricity. Despite the indiscriminate Israeli bombardment, he has chosen death over displacement. We spoke about what it’s like to live with death as a daily reality, and the engulfing smell of gunpowder and blood.

Naamat Bejjani points out that in cases of deep trauma, psychoanalysis can lead to complexities and difficult psychological conditions, “depending on the personality of the recipient of the primary trauma.” A person might experience increased tension, horror, fear, and even, the risk of death. “The surplus of negative emotions leads the body to operate outside the pleasure principle, drowning in automatic existential anxiety. Symptoms can range from hysteria and paranoia to conflicts resulting from trauma. Defense mechanisms intensify, while behavioral, psychological, and relational disorders multiply. These reactions or disturbances could appear immediately after a trauma, or much further down the line.”

Internal destruction

“Those who escape death will not escape internal destruction,” my Palestinian friend tells me while checking on our friend in Gaza, “They might be physically okay, but mentally, very bad. They will hardly be able to say that they're okay.”

Abdul Hakeem is a friend from Gaza. He has decided to hold out in his partially bombed house, with neither water nor electricity, and uncertainty as to when connection to the world will be completely cut off. Despite the indiscriminate Israeli bombardment, Abdul Hakeem and his family have chosen death over displacement policy. We spoke about what it’s like to live with death as a daily reality, and the engulfing smell of gunpowder and blood.

In this region, the trauma and horror of war and genocide, whether at the hands of the Israeli occupation or another regime, has left us drowning in our blood and destruction-filled memories. How can we live with these traumas, when our memories are loaded with images of coffins and the fresh smell of gunpowder?

He tells me, “People were safe in their homes, before they suddenly began dropping explosive barrels, destroying entire residential blocks and killing the residents inside. When we asked for civil defense and ambulances, they bombed the ambulance, killing a paramedic. And they didn't let anyone come near.” As Abdul Hakeem describes the fragmented scenes of death, the emotion is palpable. “Just imagine,” he continued, “You see your neighbor's corpse and body parts just lying in the streets. It is genocide. And then someone pleads with you to help rescue those trapped under the rubble. I try, but how? I mean, how can I lift a collapsed ceiling? I need tools, but there are no tools... That's when I broke down in tears, saying, ‘Forgive me, I can't, I swear I just can't!’ all the while, unrelenting airstrikes overhead, and the shrapnel is everywhere…” Abdul Hakeem’s greatest fear remains losing his family and becoming displaced from their Palestinian land.

In our region, the horrors of massacre, genocide and corruption -regardless of the perpetrator- haunts us. We drown in our negative feelings and memories, filled with blood, dismembered bodies, and destruction. How can we live with these traumas, and our memories, loaded with coffins and the fresh smell of gunpowder? How can we protect our sanity from the symptoms of death all around us?

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!