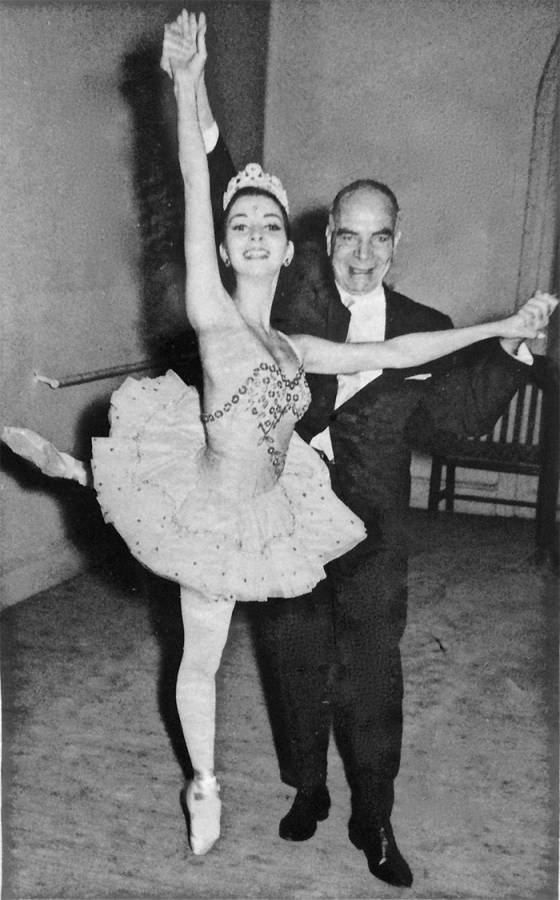

In 1966, the Cairo Opera House hosted the first Egyptian ballet performance titled "The Fountain of Bakhchisarai", featuring five Egyptian young ladies who had trained in the Soviet Union.

Despite the presence of four other girls in the show, Magda Saleh became known as the first Egyptian ballerina, narrating the story of this dance and holding onto the foundations of this classical art, whose seeds began to take root in the late 1950s with the establishment of the Egyptian Minister of Culture at the time, Tharwat Okasha, and the Ballet Institute.

Magda Saleh's name became synonymous with Egyptian ballet, as she gained remarkable fame and was chosen by the Russian Bolshoi Ballet troupe to participate in one of its performances.

For the past few years, between March 13 and 18, she is honored by the dance and theater company "From the Horse's Mouth" in New York. During the event, two documentaries on the history of dance in Egypt were presented: "A Footnote in Ballet History?" directed by Hisham Abdel Khalek, and "Egypt Dances" (1977), in which Saleh starred and provided commentary.

Here, we get to know Magda Saleh, from the moment she took flight as the "butterfly of ballet," as she is known, on the stage of the Opera House, saying, "Look at me, I have a story to tell you."

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina, dancing on stage

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina, dancing on stage

"I knew this is what I wanted to do for my entire life"

Saleh's story as a dancer, dance instructor, and director of the opera house later, then her subsequent move to live in the United States, reflects what Egypt has experienced over the past decades, from enthusiasm for political, ideological, and cultural experiments to periods of cultural shocks.

Her life journey stands in contrast to the situation of many women in Egypt as she sought to "reinvent herself" and achieve her lifelong passion to become what she has dreamed to be since she was a young child: a ballet dancer.

"I knew this is what I wanted to do my entire life".. Magda Saleh began learning ballet at a young age, and her passion for it only kept growing, even though her father reluctantly accepted it since talking about dance at the time was seen as a scandal

"I wouldn't have become the person I am now if I hadn't gone through all that. If I had stayed in Egypt, I would have been like any ordinary Egyptian girl. I would have grown up and gotten married like most women in the Middle East," she said in an interview with Shelter Island Reporter.

In one of her interviews, Saleh recalls, "I was taking ballet lessons and thinking that my teacher was dancing in the Bolshoi, and as I watched her, I felt a sensation I couldn't describe. That's when I knew this is what I wanted to do for my entire life."

She grew up in Cairo with three siblings to an Egyptian father and a Scottish mother. Her father was one of the first graduates of the Faculty of Agriculture at Cairo University and received a scholarship to study in Glasgow, where he met her mother, who returned with him to Egypt, and they got married in 1937.

Saleh began learning ballet at a young age, and her passion for it grew during her teenage years, even though her father reluctantly accepted it because talking about dance at that time was considered a disgrace.

Saleh narrates, "He was a prominent academic, and from his perspective, he saw that my pursuit of dance would plunge me into a social war. He wasn't happy with my career choice at first, especially given the stereotypical idea about dancers and artists in Egyptian society," she recalls.

Nevertheless, Saleh joined the Alexandria Conservatoire School, which had a ballet department supervised by teachers from the Royal Academy of Dance in Britain, before they left Egypt due to changing political circumstances.

In 1958, the Russian "Moiseyev" dance company came to Egypt for a tour that included Alexandria. "At that time, the director was invited to watch the young local ballet children, and he summoned me... I remember he told me that I was talented, and there was a teacher from the Bolshoi School coming to start a similar one in Cairo, and that I should apply," according to Saleh herself.

By the time she turned 14, she was studying with a Russian faculty at an academy supported by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture. It was like a university for arts, comprising seven institutions, with ballet being one of them. Every year, more Soviet professionals would come on a nine-year academic training program.

"They couldn't believe that we were Egyptians"

After five years, Magda and the other four, Diana Hakak, Nadia Habib, Alia Abdel Razek, and Wadoud Fayez, were selected for a scholarship in Moscow.

Saleh recounts that experience, saying, "We graduated after two years from the Bolshoi Academy there... Moscow was definitely a challenging experience for us. We were like those spoiled little girls when we arrived there, but we learned how to take care of ourselves by the time we returned at the age of 21. We were prepared to face the world."

She recalls in the documentary film "A Footnote in Ballet History" by director Hisham Abdel Khalek what one of the teachers said when she asked them not to show up in front of their Russian peers with new dresses every time, because most of them only had one dress for the entire year, despite being from "the developing country aided by the Soviet Union."

"My father was a prominent academic, and he believed that my pursuit of dance would plunge me into a social war. He wasn't happy with my career choice at first, especially given the stereotypical idea about dancers and artists in Egyptian society"

The five young women formed the core of a professional troupe in Egypt, after training for a whole year for the awaited moment, which was the first Egyptian performance in 1966.

The Minister of Culture at that time, former army officer Tharwat Okasha, was keen to attend the rehearsals of "his children," as he called them. And when the moment came, the Egyptian audience was astonished by their level of performance, as "they couldn't imagine that we were Egyptians," according to Saleh's testimony.

Later, President Gamal Abdel Nasser attended the performance, and they were awarded the Order of Merit by the state.

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina

"Our only goal was to deliver a good performance. We trained for more than a year. All our previous ballet performances involved training, and I focused on my own performance. But to have a purely Egyptian performance presented at the Egyptian Opera House... It was a completely different feeling."

After the success of the performance in Cairo, the Ministry of Culture decided to move it to Aswan, which surprised people. Whom would the ballet perform for "in the land of the High Dam"?

After the performance there, the audience was amazed. "I was surprised by a humble-looking man wearing a galabeya (traditional robe) who entered the backstage area and looked at me. When I asked him why he was there, he replied, 'Wow, young lady, this is a truly beautiful thing.' That's when I realized that the feeling of the performance had reached this simple man," according to Saleh's account.

In an interview, Saleh explained that during that period, "there were many taboos, prohibitions and objections to dance and dancers. However, Egyptians love dance, joy, and life. Look at Egyptian celebrations, and you will find that dance is an essential part of our lives as human beings."

"A humble-looking man wearing a galabeya traditional robe wandered into the backstage area. When asked why he was there, he said: 'Wow, miss, this is a truly beautiful thing!' That's when I realized that our performance had even reached this simple man"

"I cried when the Opera House burned down"

Magda was at home when the Cairo Opera House caught fire in 1971. She recounts, "A fellow dancer came to me on his motorcycle and told me about the Opera House fire. I jumped behind him, and we headed to the city center, where the Opera Square was located. There were hundreds, maybe thousands of people, all standing in silence."

She adds, "Nearby, there was a main fire station, but it only had the water pressure for two hoses. It was a pitiful effort. We all stood there and cried. It was a terrible moment. It was the end of an era and a devastating blow to all cultural and theatrical activities in Cairo."

Regarding another incident that occurred during that period, which started after the setback of 1967, she says that she was supposed to travel outside Egypt for a performance. She had to go to the Ministry of Information to obtain permission since, at that time, "everyone in Egypt had to get permission to travel."

There, according to Saleh, she met an employee who, upon seeing her occupation written on the passport as "ballet dancer", told her, "There needs to be approval from the morality police." The "ballet dancer" did not travel because her father was furious about this situation.

"There were hundreds, maybe thousands of people, standing in silence. We all stood there and cried. It was a terrible moment, the end of an era and a devastating blow to all cultural and theatrical activities in Cairo," Saleh recalls the Opera House fire

After the Opera House fire and the changing circumstances surrounding it, her mother advised her to face the reality of what had happened. "She told me that if I wanted to continue dancing, I should find another path."

With the help of her family connections, as her father was the Vice President of the American University in Cairo at the time, she applied for a scholarship to study arts and traditional dance at the University of California, where she obtained a master's degree, and then a doctorate at New York University.

During that time, she also participated in the production of a documentary film about traditional dances of the Nile Valley called "Egypt Dances". She traveled all over Egypt, documenting 20 different types of dance.

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina, dancing on stage

Magda Saleh, Egypt's first prima ballerina, dancing on stage

She returned to the Cairo Opera House, then was expelled from it

In 1983, she returned to Cairo to work as a professor and later dean of the Higher Institute of Ballet. 17 years after the fire that changed her life, she was appointed as the director of the new Opera House.

"I am afraid that the art of ballet will be confined within the walls of the expensive Opera House," Magda said in an interview with the "Shabab Baladi" publication in 1989, as documented in the archives of the Library of Alexandria.

She believed that "culture is not a luxury but rather an essential part of society." However, the saga of bureaucracy, wasteful spending, and political disputes eventually led to Magda's removal from her position, stifling hopes for a "new era", as described by Abdel Khalek, the director of her documentary film.

News reports document the details of her dismissal, a troublemaker who did not have a fair chance, to the point where her office was sealed with red wax and she was expelled from the Opera House. The reason for the decision made by the former Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosni, was not mentioned at the time. However, the circulating rumor was that the reason for the minister's annoyance with her actions was because she completely bypassed him and directly invited former President Hosni Mubarak to attend the opening of one of the performances.

After that, she returned to the United States in 1992 to devote herself to education at New York University. She officially retired from dancing in 1993 due to a back problem and married the Egyptologist Jack Josephson at the New York Institute of Fine Arts.

In 2012, she was asked about her stance on the January 25th revolution and Tahrir Square, and she said, "Some people feel that everything is collapsing, and some are very optimistic... I am very proud of what they have achieved, I'm very proud to be Egyptian."

She still felt regret for not being able to serve her country, but she said, "Egypt is with me", indicating her efforts to support Egyptian artists in the United States.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!