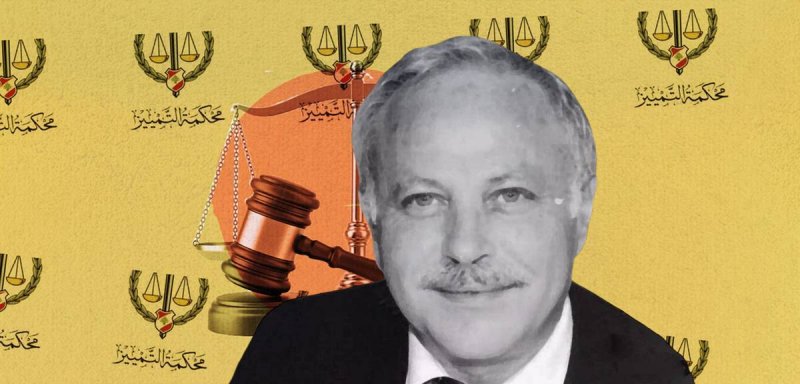

The Public Prosecutor of Lebanon’s Court of Cassation, Ghassan Oueidat, walks the corridors of Beirut’s Justice Palace securely chaperoned by heavily armed guards. Inside the palace, opposition deputies meet with Justice Minister Henry Khoury to demand his dismissal, while outside, a demonstration and an attempt to storm the Justice Palace by the families of the victims of the August 4, 2020 explosion, and opposition activists are met with a fierce clampdown. Here, too, their demand is the dismissal of the public prosecutor for what they see as his “unconstitutional coup”.

What did the honorable Judge do? Almost a year after the investigation into the port explosion was halted, due to a rebuttal lawsuit filed by some of the wanted and accused persons against the judicial investigator in the case, Judge Tarek al-Bitar, and because the Plenary Assembly of the Court of Cassation — which is authorized to make the decision on these rebuttal lawsuits in order to relaunch the investigation — was suspended through rebuttal lawsuits also filed by some of the wanted and accused persons against the Assembly's judges, Judge Bitar decided to return to the investigation based on a legal review that his dismissal was unconstitutional.

Al-Bitar's first decision was to prosecute Ghassan Oueidat due to his role in the port explosion case. In response, Oueidat charged al-Bitar with the crime of "usurping power", issued a travel ban against him, and released all those arrested in the case.

“Oueidat’s coup”

Lawyer Nizar Saghieh, Executive Director of Legal Agenda and one of the founders of the “Independence of the Judiciary Coalition in Lebanon”, tells Raseef22 that what happened was a “complete coup”. He says, “Oueidat played the role of someone who has been personally wounded, but the real outcome was using it to implement certain political goals, as was required of the substitute judge whom the political authority tried to appoint to implement its goals instead of al-Bitar. He was able to implement it by releasing the detainees in the case, and issuing his decisions despite the claim against him in the port case, bypassing his recusal (withdrawal from the case due to a conflict of interest) from the file.”

Public Prosecutor Oueidat charged Judge al-Bitar for “usurping power”, issued a travel ban against him, and released all those arrested in the Beirut Port Explosion case

Saghieh explains, "Oueidat decided to retract his mandatory resignation based on the Code of Civil Procedure, given his ties to the case and his familial ties with defendant and former minister Ghazi Zaiter. Thus, his situation differs from that of Judge al-Bitar, as the court did not take any decision against him in the matter of his dismissal from the case, while the Court of Cassation did make a decision to accept Oueidat's recusal, and therefore there is a judicial decision that prevents him from returning to the case, and yet he still returned and breached the judicial decision."

He adds, “He used competences and jurisdictions he does not have, and released the detainees, or rather smuggled them out, relying on political power over the security services, and this is a crime in the penal code, then he sued the judge who is looking into his case.”

Based on the fact that interfering in the judiciary is a crime punishable by up to three years, Saghieh asks, “What if the wanted person had filed against the judge investigating his case?” He then replies, “This is one of the biggest crimes against the judiciary, and it's one of the biggest acts of coercion against a judge. From here we see that Oueidat is enacting a coup against the law and the judiciary.”

Saghieh’s position on Oueidat’s behavior intersects with other positions that have resonated in the Lebanese street. About forty deputies came together, counting what had taken place as "a destructive coup, which began, when justice was castrated with the ensuing surreal sequence of events that lack legitimacy" calling for immediate accountability for the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation.

For its part, the Lebanese Judges Association, which is composed of a number of independent judges, said that Oueidat's reaction "went beyond all limits and principles in a flagrant manner that destroys the foundations of justice and law.” It called on "all those who are content with not acting as judges, and have sold themselves in service of political authorities and injustice, to resign in preparation of being accountable because they no longer resemble us and have contributed to undermining the stature of the judiciary, the rule of law, and institutions."

Similarly, the Beirut Bar Association considered that it is “not permissible for the Cassation Public Prosecutor, who is already recused, and whose recusal has been duly accepted, to take any decision or action in the case, which constitutes an abuse of power and a violation of the law, and requires him to respect due process and legal principles. He must retract his decisions which carry grave errors, and let the investigation take its course through the duly appointed judicial investigator.”

The Independence of the Judiciary Coalition, which includes human rights organizations, associations, and groups, announced that it "will spare no effort to hold the persons involved in this coup accountable, sooner or later, as part of the battle for comprehensive accountability."

“Guarding” the nitrate

The two defendants, Judge Oueidat and the Court of Cassation Public Attorney Ghassan Khoury, had previously investigated the ammonium nitrate file before the explosion occurred. Major Joseph Naddaf, the head of the State Security office at the port, presented them with a report he prepared about the presence of a large amount of ammonium nitrate in hangar No. 12. The report had clearly indicated “there are 2,750 tons of nitrate, which is a substance used to manufacture explosives, as it is highly flammable and highly explosive, and that after consulting a source specialized in chemical science, he confirmed that if ignited, it would cause a huge explosion, the results of which would be almost completely devastating to the port of Beirut.”

At that time, Oueidat in response contented himself with requesting to secure a guard for the hangar, close the hole in the wall of hangar No. 12, and seal its entrances, while the latter decided to close the investigation without removing or properly storing the dangerous substance.

“Oueidat didn't empty the hangar, but rather closed it, thus keeping the dangerous substance in the port. Did he make the decision out of ignorance, lack of understanding, negligence, or because someone asked him to do so? This opens up room for investigation”

In Saghieh’s opinion, “The role of the public prosecutor in the matter was worrying, because he already had a prior opinion about the ammonium nitrate, as he did not make the decision to empty the hangar, but rather to close it, thus keeping the substance in the port. So did he make the decision out of ignorance, lack of understanding, negligence, or because someone asked him to do so? This opens up room for investigation. From here, he should have stepped down, and the government should have appointed another public prosecutor in this case.”

He bases this opinion of his on “the Civil Procedure Code, so that the judicial investigator can carry out the investigation with him like any other person. However, this did not happen, and he stepped down and appointed another prosecutor in his place, Ghassan Khoury, who also had a role and ties in the case. And he did not step down immediately, but waited until his relative, Minister Zaiter, was summoned, about a year after the explosion.”

Regarding his role in the investigation, Saghieh explains that, “Throughout the investigation period, the Public Prosecution refrained from attending the interrogation sessions in the port case, citing Oueidat's withdrawal, as if its other judges were not involved in the investigation, making it easier for the defendants to evade, by stalling in expressing opinion on the formal defenses they submitted for not appearing before al-Bitar, and allowing them to file counter claims to obstruct the investigation. In addition, his opinion has always been that ministers and MPs cannot be prosecuted.”

He continues recounting what Oweidat did, "When al-Bitar issued an arrest warrant against former minister Ali Hassan Khalil, the Public Prosecution obstructed the implementation of the warrant by restricting its implementation outside the regular session of the parliament, where it was aware that the parliament was mainly convening due to the parliamentary elections. In addition, he had adopted a more lenient policy and made no effort to compose or develop the file. The judicial investigator has always been the one who is doing all the effort and the public prosecution is the one who is obstructing."

“The judiciary’s superman"

Oueidat's performance in the matter of accountability in the port file is not separate from his performance as a public prosecutor with broad authority that made him an absolute master in the judiciary, and consequently in investigating crimes and in pushing or dismissing public cases, as Saghieh explains.

Since Oueidat took office, he has expanded his already broad authority according to the law, so much so that we can now even call him the 'Superman of the country’s judiciary’.

“Since he took office, he has expanded his already-broad powers according to the law, so much so that we can now even call him the 'Superman of the country’s judiciary’,” he says. He has expanded his powers to pre-censor the work of prosecutors who are administratively subordinate to his authority. He issued a decision in September 2019, obliging prosecutors to inform him of public interest cases and corruption cases related to the public administrations they are investigating, citing that they are serious crimes in which everyone must act according to his orders and directives, pursuant to Article 16 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.”

Saghieh adds, "The second aspect of the expansion of the hierarchical organization within the Public Prosecution was the transformation of the Discriminatory Public Prosecution Office from a directive and supervisory authority to a direct intervention authority. In some cases, it went to confiscate the powers of its public prosecutions, by imposing the order that all the correspondences of the Public Prosecution must be conducted via and through it."

There are many instances in which the Cassation Public Prosecutor had relied on a "frightening hierarchy to control all the work of the Public Prosecution", refuted by the Executive Director of Legal Agenda Saghieh, who says, "When Judge Jean Tannous decided to raid six banks to obtain data on the transfers of Raja Salameh, the brother of Banque du Liban Governor Riad Salameh, Ghassan Oueidat intervened to stop the raid in January 2022. At the beginning of the banking crisis in March 2020, Oueidat, in a judicial precedent, froze a judicial decision to freeze the assets of 21 banks and the assets of their owners, and instead of investigating the bank owners, he met with the bureau of the Association of Banks and published the minutes of the meeting, which gave a kind of cover for their procedures.”

He adds, "Oueidat also charged Judge Ghada Aoun, after she demanded that the law to lift banking secrecy be applied to track the accounts of a group of Lebanese officials abroad, and he prevented her from communicating with any of the Internal Security Forces, bypassing the limits of the authority entrusted to him under Article 16 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. He even went on to impose an immediate punishment on Judge Aoun."

In his view, "The Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation was using his broad powers, which he allowed himself to expand further, in order to perpetuate the system of impunity and thus implement the political power’s agenda."

"The Absolute Sultan of the Judiciary"

To delve deeper into the broad powers of the Cassation Public Prosecutor, we spoke with the President of the Lebanese Center for Human Rights (CLDH), Wadih al-Asmar, who is familiar with the role of the Cassation Public Prosecutor in Lebanon. "The Code of Criminal Procedure gives the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation all the powers that enable him to be an absolute authority in the judiciary," says al-Asmar.

The powers of the Cassation Public Prosecutor were extended to its maximum during the time of Syrian influence in Lebanon. What’s even more dangerous is that the Council of Ministers appoints this position, which means it's the instrument through which the political authority controls the judiciary

These powers include: "Issuing written or verbal instructions in the conduct of public law proceedings and criminal prosecutions that require a license or permission to prosecute from a non-judicial authority; imposing a disciplinary penalty on any public prosecutor who he may find negligent in his work, by alerting him or referring him to the disciplinary council; monitoring the work of judicial officers and verifying their performance; reviewing the investigation files undertaken by an investigative judge and requesting the Public Prosecutor to provide a report that is consistent with his orders and directives; requesting the reversal of judgments or penal decisions; requesting to appoint a reference; and requesting to transfer the case from one court to another."

In addition to these jurisdictions, according to al-Asmar, the position allows for “prosecution in crimes referred to the Judicial Council; prosecution in crimes committed by judges, whether arising from or outside the position; representing the Public Prosecution before the Criminal Court of Cassation and the Judicial Council; preparing files for the recovery of criminals and referring them to the Minister of Justice, along with its reports; and drawing up a detailed report to be attached to the file of any person on death row when he is referred to the Special Amnesty Commission.”

These jurisdictions and powers, as al-Asmar recounts, “were consecrated during the time of Syrian influence in Lebanon. In 2001, after the parliament drafted a new code of criminal procedure, which to some extent corresponded to the international standards adopted at the time in terms of the independence of the judiciary and respect for the roles of prosecutors and the rights of detainees, the then President of the Republic, Emile Lahoud, in coordination with the then Prosecutor General of the Court of Cassation Adnan Addoum, the Director General of General Security Jamil al-Sayyed, along with the Syrian intelligence, restored the law and asked the parliament to re-examine it.”

This coincided with the events of the 7th and 9th of August, which witnessed the arrest and suppression of dozens of activists against the "Syrian occupation".

These events, according to jurist and human rights activist al-Asmar, "were carried out to put pressure on the deputies, and soon after, the parliament retracted what it had approved, and introduced amendments that expanded the powers of the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation to it maximum limits, and what’s even more dangerous is that this position is appointed by the government, which means that it is the instrument through which the political authority controls the judiciary.”

The authority’s “big stick” policy

Regarding the political role played by the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation, MP George Okais, who has also been a judge since 1994, before deciding to resign in 2010, says that "after the Taif Agreement that ended the Lebanese war in 1990, it’s not possible to separate the person appointed to this position from his hidden quest to reach political positions. Because the Court of Cassation Public Prosecutor — after the end of the time of war and our entry into the era of Syrian influence — became a tool in the hands of the political authority, which was controlled by the ‘Syrian guardianship’ authority, the judicial and security messages that the ‘guardianship authority’ wanted to send were done through the Cassation Public Prosecutor.”

Following the Taif Agreement that ended the Lebanese war in 1990, it’s not possible to separate the person appointed to this position from his hidden quest to reach political positions

He explains that, “Just like any officer from the Maronite community aspires to be commander of the army, and then president of the republic, likewise, every Sunni judge aspires to be a prosecutor of the Court of Cassation and hopefully become head of government. This is the highest judicial position and the law gives him broad authority and the ability to influence society in a major way, and these jurisdictions were strengthened by the Code of Criminal Procedure, which was amended in 2001, at the height of the Syrian grip on Lebanon."

"Before the time of Taif and Syrian influence, we would rarely mention the names of the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation, because their practices had still been conducted under the roof of the law and were consistent with a general conservative judicial behavior that does not interfere in politics and does not accept political interference. However today, we find that the first position that is highlighted in the country’s judiciary is that of the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation, more than the Head of the Supreme Judicial Council, the Chief of Judicial Inspection, and any other senior judicial position, as he is appointed by the political authority and holds sensitive public files, and if he starts to misuse or abuse power, he’ll be able to go far in exploiting his influence and authority," says Okais.

He adds, “The Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation was the big stick in the hands of the authority, in a way that contradicts the concept of the Public Prosecution, which should represent the interests of society and not the interests of the state, and this began with Mounif Oueidat, then Adnan Addoum, then Saeed Mirza, and finally Ghassan Oueidat."

The president of the Lebanese Center for Human Rights points out that "the demand to amend the powers of the Public Prosecutor of the Court of Cassation in the current law is not new, even if this was done in a separate step from adopting the law on the independence of the judiciary, because its powers are very dangerous and affect human rights and the accountability process, and we cannot wait to reduce them.”

On this, Saghieh adds, "We must reduce the powers of the Cassation Public Prosecutor in the Criminal Procedure Code, because these powers enable him to impose a frightening influence on the judiciary in general, which contradicts the powers of public prosecutors in comparative law."

Saghieh concludes, “It is enough to recall the experience of Adnan Addoum during the time of Syrian influence, as that era was described as the ‘Addoumi’ judiciary – just to get a grasp on this frightening hierarchy that dominated the justice system during that juncture. Therefore, pending the issuance of the promised law of independence of the judiciary, and while this hierarchy was expected to be mitigated by legislation to give greater independence to public prosecutions, the current Court of Cassation Public Prosecutor, Ghassan Oueidat, went in a completely opposite direction in order to strengthen his hierarchical authority over the judiciary. He went so far as to overturn the logic of the Rule of Law”.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!