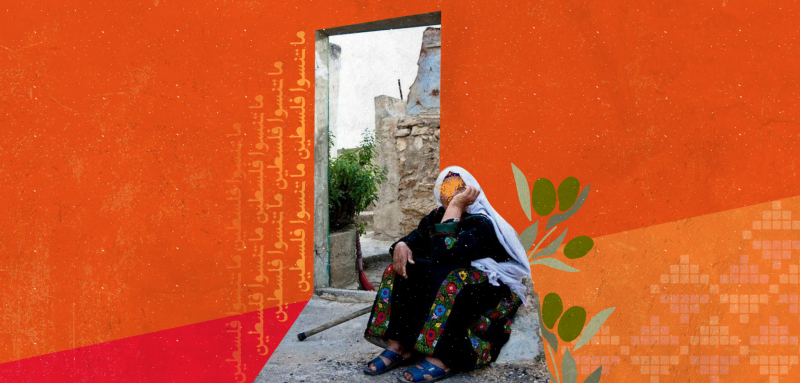

My grandmother recounts the long story of her childhood in Palestine as if she is living it right now. When she talks, my grandmother (Umm Marwan - 87 years old - born in Palestine in the village of al-Ghabisiyya, north of Acre), seems as if she’s holding every small detail in her two hands, from playing in the vicinity of her village mosque until Nakba day in 1948. I sit with her in the evenings, and we do not talk much about the present because she does not remember much of it the way she remembers her distant past and her childhood in Palestine.

She begins with, “You see, my dear boy, we had many large groves and orchards, and my father and mother used to work in them. I would play around them and they would yell at me: ‘Siham, aren’t you tired of playing yet?’” I look into her eyes as she reminisces, and I imagine myself with her there. I imagine every detail of our village that has been occupied since 1948, and when I’m done visiting her and I get up to leave, she tells me, “My son, where are you going so late at night? Is it not dark outside?” I say to her, “Grandma, it is still six in the evening”. She says, “I swear I can’t remember anything anymore”.

While she would tell me about her childhood nearly seven decades ago, she is always saying that her memory has completely faded aside from the time she lived in Palestine, which she remembers in all its small details. I walk out of her makeshift home in the Nahr el-Bared refugee camp, as I grow more aware and think about the scenes of her moving story about that country that we lost.

If only my grandmother could write down this story of hers, because her account is the holy testimony that proves that the ownership of the land belongs to the original people living on the land. If only she could write it down before the sacred aspect of the Palestinian memory vanishes. And she is the one who always says, “Today, I can tell (my story), but tomorrow, I don’t know what might happen to me.”

When journalists would visit to film interviews with her, they would be surprised by her never-ending words and tales about her village in Palestine. She recounts as if she is living inside her own story — and she always asserts that she is living there within that story and within its scenes that can never be erased from memory. She always says she hates the present and hates everything she went through after taking refuge in the Nahr el-Bared refugee camp in northern Lebanon, even before she reached the age of 87.

She does not care, or rather does not remember much about the things and details that have to do with the camp. She sees it as a part of her story, but not the part that she considers to be so tragic that she needs to hold on to its every detail. My grandmother respects the guests and relatives who visit and call on her and loves them very much. She respects those who have mastered the art of listening to her stories while she talks about Palestine, her guests usually sit with her for hours on end. When I would visit her, she used to say to me, “Your aunt just left, and she had been with me since the morning, may God bless her.” I would ask her, “What did you two talk about?” And she would reply, “We were talking about Palestine,” and I would say to myself, ‘Oh so that’s why the visit went on for so long.’ It is as if my grandmother, the oral narrator and novelist who forcibly distributes the words of her story to her readers, is aware of the importance of what has been etched and engraved in her memory.

When journalists visit my grandma for interviews, they’d be surprised by her tales of her village in Palestine. She narrates as if she’s living inside her own story and within its scenes that can never be erased, always saying she hates the present

I wonder if, God forbid, my grandmother died after having lived a long life, who would keep this historical account alive after she’s gone? Or what if one day I was unable to retell it? My grandmother’s story is the holiest tale on earth, because it is the story of a people who were forcibly uprooted from their land, and I often imagined her telling me her account. My grandmother is an epic heroine in her novel, ever since she was driven out from her village of al-Ghabisiyya into southern Lebanon, and then to the Nahr el-Bared refugee camp in Lebanon with her father, mother, and a few members of her family.

None of Homer, Dostoevsky, or Márquez are any better than my grandmother in her chronicles and narrative account, and the way she captures the details from the memory of the 1948 Nakba. She is very careful not to forget or lose a single detail. Not a single mistake is allowed in any sentence or part of the account, and she must keep recounting the events that happened in a very accurate manner. When I once took her in my car from her house in the camp to our home for a family visit because she can no longer walk, she said to me. “My son, I can no longer walk now, but during our days in Palestine we rode on donkeys and there were people who walked, but now we need cars to transport us, my dear boy.” I noticed that she no longer cares about the way the camp looks, and she does not care anymore whether the street is wide or narrow, or if the houses have or haven’t changed. Details such as these do not mean anything to her now that she is over 87 years old, but she feels that the memory of Palestine for her is the reason for her interest in constantly thinking back on those days — she is holding on to her memories more than she is holding on to her present reality.

On the contrary, she criticizes this current reality and praises the past, leaving behind the pleasures of life. She is always expressing her wishes and desires, saying, “My dear son, after I die, do not forget Palestine. Palestine cannot be forgotten.” These wishes are part of her oral narrative. She would talk about Palestine every time I try to make her listen to me when I talk to her about the camp and its people. She cuts through my words with her endless wisdoms, and I get another feeling that I am talking with two different accounts. My grandmother is living two stories, not one; the first is the story of Palestine before and after the Nakba, and the second is the story of her plight seeking refuge and the tragedy of the Nahr el-Bared refugee camp — the anniversary of which happens to fall on May 20. But my grandmother leans more towards her first story, and may not even remember anything about the second one. She always says, “Wherever the camp may be, it all doesn’t matter in the end, my son, and there’s nothing left of this life.”

She no longer cares about the way the refugee camp looks, or if the street changed. They mean nothing now that she is over 87. The memory of Palestine is why she's constantly thinking back on those days - she's holding on to memories more than the present

If I reminded her of Palestine, her “first story”, she would have fully narrated it to me tirelessly without ceasing or stopping, chronicling it in accurate detail and with such a passion in her words, as if she was a child again and was playing in the mosque square and in the field near her home in the village of al-Ghabisiyya, near the villages of Kuwaykat, Shaykh Dawud. and Al-Kabri, Sometimes she talks to me about the girls who used to play with her, even going so far as to recount the full names of each and every girl. And her story always ends with, “I wish we would return to Palestine.”

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!