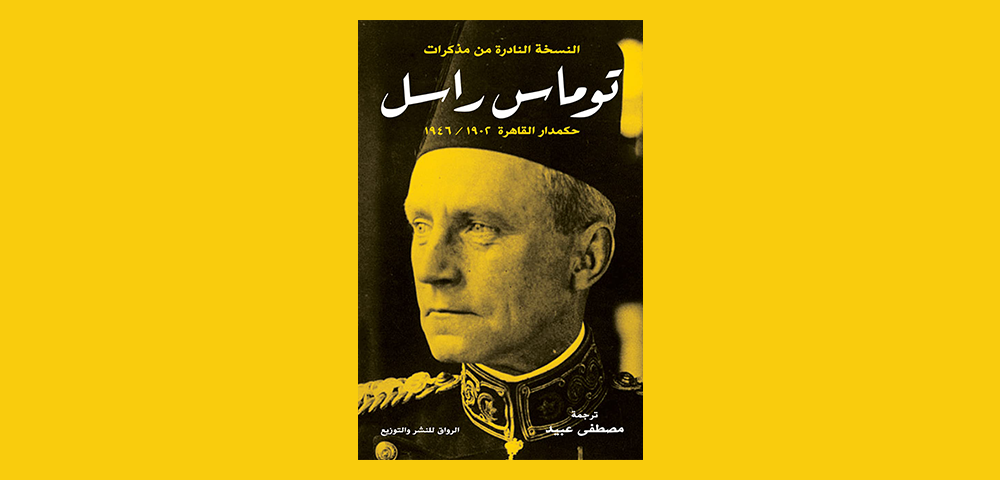

The memoirs of Thomas Russell, one of the most famous officers in the Egyptian police, came out during the British occupation of Egypt, as a social and security document on the conditions of society in the first half of the twentieth century.

Nearly 70 years after Russell’s memoirs were published in London, the Arabic version was issued by Dar al-Rewaq publishing house in Cairo.

At the time, Britain was overseeing the functioning and performance of Egypt’s ministries and agencies, through a system of English inspectors who had a supervisory role to install British governance systems, to act as colonial seeds planted in the heart of Egypt’s key sectors. Percy Machell — Russell’s cousin — was an inspector at the Egyptian Interior Ministry, spurred by his cousin, Thomas Russell came to work as a Police officer in 1902.

Russell began his journey in Egypt as a trainee with the “coast guard” in Al Max, west of Alexandria. The main task of the coast guard was to prevent the smuggling of drugs into Egyptian villages and cities.

In January 1903, when Russell was 24 years old, he took on the position of deputy inspector in the Beheira Governorate. From there, he then moved on to several governorates in the Delta region, until he became inspector in Upper Egypt in 1908. In 1911, he became assistant commandant of the Alexandria police, then assistant commandant of police in Cairo, until he reached the position of commandant of the Cairo police in 1918, and remained in the post until his service ended in 1946.

Even though Russell’s arrogant colonialist tendencies dominate parts of the memoirs, it is an impartial and objective testimony for the most part, revealing the hidden mysteries of the world of crime, drugs, prostitution, gambling, and banditry

The importance of Thomas Russell’s memoirs, which were issued in London after 1946, lies in the fact that it is a rare document that reveals the dark and unknown aspects of the social life of Egyptians, during a period that witnessed many fluctuations and changes within the conditions and characteristics of society. Even though Russell’s arrogant colonialist tendencies predominate in some parts of the memoirs, it is still an impartial and objective testimony for the most part, revealing the hidden mysteries of the world of crime, drugs, prostitution, gambling, and banditry.

On the other hand, it is an enchanting journey in the deserts of Egypt, where Russell roamed as a tourist and a skilled hunter in search of birds and wild animals. His travels saw him establish strong friendships with known Bedouin and Arab figures who work as experienced guides and trackers in the desert.

The crimes of privileged foreigners

The police institution in Egypt at the time was run according to the same system that had been followed since the era of Napoleon, which states that determining the charges for the accused is done via the prosecution within the Ministry of Justice. This system, according to Russell, had many negative drawbacks, but the real obstacle standing in the way of the Egyptian police work, was the system of foreign privileges, under which controlling the crimes of Europeans living in Egypt was difficult, as they could not be tried under Egyptian law and would always take refuge in their consular courts.

Russell says, “Any home belonging to a foreigner could not be entered without an official permit from his consul. So it was not surprising that the crimes of foreigners thrived under the blanket of these privileges, and the police felt vexed and frustrated whenever foreign criminals were released.”

A murder every 3 hours

Russell opens his documentation of the world of crime in Egypt with official statistics. The numbers reveal that murder was the most prevalent crime in the countryside, and that 80% of murder crimes were for revenge, while 18% were for theft. Killings had become so common that there was a murder taking place every three hours in the countryside, and they no longer drew the attention of the farmers, who — according to Russell — would turn into murderers in the blink of an eye, despite their calm and peaceful nature and great sense of humor.

Aside from murder, “robbery” was a common phenomenon that was taking place in various parts of the country, especially in Upper Egypt. The robberies were being carried out by gangs that were usually headed by “half-Sudanese” individuals. These gangs continued to intimidate citizens, until they were eliminated by the ‘Camel Corps’, which was founded by Russell in 1906 and consisted of Sudanese men known for their strength and brutality.

Russell points out — through several chapters where he had documented aspects of the social life of peasants and Upper Egyptians — that the law regulating the relationship between individuals and the state was marginal in contrast to the other informal (social) law that was formulated by farmers and Arabs, in accordance with the prevailing customs, traditions, and norms.

Russell confirms that this social law was the prevailing and governing law among the people, unlike cities which were subject to official government laws. He also tracks the manifestations of extreme poverty that the peasants were living in, “and how an entire family can survive on a daily income that does not exceed a few piastres (coins), that barely provide them with bread made of corn,” He also mentions the collapse of healthcare of farmers, which took place mainly due to the spread of two dangerous diseases: schistosomiasis and ancylostoma. Schistosomiasis had only been confined to the delta region, but then moved to Upper Egypt after the irrigation system changed from “basin irrigation” to “continuous irrigation”.

Russell saw that the farmers’ drug use at the time was a direct result of the spread of these serious and debilitating illnesses, and hence resulted in their urgent need for “stimulants” to strengthen their abilities and willpower.

Trackers and police dogs

In his memoirs, Russell lists the various methods used to trace criminals, the most famous of which was “tracking”, a skill that the Bedouins and desert dwellers were known for. Through this mode of “tracking”, it was possible to follow the trail of criminals, and even determine their age, weight, and type, even if the surface of the ground was solid.

As for police dogs, Russell devotes an entire chapter to them, telling amazing stories about the abilities of “Hol” the dog, who helped the police detect and uncover more than 170 crimes.

Dubbed “Captain Hol”, the canine was an extraordinary discovery made by a young Egyptian officer named Alfie, who had spent many years studying and specializing in canine training.

Hol was distinguished by his extreme intelligence, and had remarkable abilities to track scents for several days. One of the most important crimes that Hol uncovered — which was also personally related to Russell — included successfully detecting three Arabs who had killed “Judah”, the hunting aide who used to work with Russell on a number of hunting trips.

The commandant of the Cairo police says, “The mere appearance of Hol in many of the cases and on the scene of the crime, was a direct reason for the guilty person to immediately confess to the crime before the dog exposed him. Hol was the most famous employee in the country’s police, and had a large audience that included hundreds who would gather to watch him identify and expose fearsome criminals.”

The strange influence of Ibrahim al-Gharbi

Here, Russell reveals the details of the world of prostitution, gambling, and human trafficking. Prostitution was mainly concentrated in two places. The first was “Wagh El Birke” on Clot Bey Street, and in the past it was known as the European neighborhood with its hotels and consulates, before it became a neighborhood inhabited by European women who obtained a license to practice prostitution. The second was “Al-Wasaa”, the officially licensed neighborhood that was inhabited by Egyptian, Nubian, and Sudanese women.

Russell spoke of a person named Ibrahim al-Gharbi. Dubbed by some as ‘the king of Cairo’s red-light district’, al-Gharbi was in control of the “al-Wasaa” area with all its women and pimps. Through close surveillance and investigations on him, Thomas Russell inferred the amazing influence that Ibrahim al-Gharbi, the self-proclaimed ‘King of the Underworld’, had in Egypt, “This man had a strange influence in this country, and this influence was not limited to the world of prostitution, but extended to politics and the elite society. The buying and selling of women as commodities in Cairo and the rest of the provinces did not take place without the permission of this Western man.”

By decision of “Harvey Pasha”, commandant of the Cairo police at the time, and with the help of his deputy assistant Thomas Russell, the police launched an extensive campaign “to clean up these areas littered with prostitutes and transvestites”. Subsequently, about a hundred girls were detained over the course of two nights in a shelter camp in al-Helmiya, with Ibrahim al-Gharbi with them. He spent a year in Helmiya camp, then returned to his hometown, “Wadi al-Arab” in Aswan. There, he returned to prison once again as a result of his criminal actions after being sentenced to five years imprisonment, and later died in prison.

Foreign privileges were a major obstacle to Russell when dealing with the unlicensed brothels that were owned by foreigners, as the police could not enter a foreigner’s home without permission as well as the presence of his consul. Russell faced great difficulties regarding this issue until he was finally able to break into these brothels and conduct his investigations. He also faced the same difficulties trying to break into a large casino on Emad el-Din Street, where the owner was in direct contact with his country’s consul.

At the same time, Mortz Spiegel, a Jewish white-slave trader who had committed murder and escaped to Mexico City, was tracked down and arrested. His capture and subsequent sentencing to life imprisonment was — according to Russell — “a painful blow to the slave trade market in Egypt, after they realized that a killer could be arrested even after seven months and brought back from places as far away as Mexico City.”

Drugs, malaria, and the year of doom

In his memoirs, Russell singles out three chapters where he tells of the route of drugs in Egypt, the ways they were smuggled, and the adventures he undertook to arrest merchants and smugglers. Russell went on to achieve great success in these cases by establishing a central drug enforcement office, now known as the “Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau (CNIB)”.

Russell recounts the first appearance of cocaine and heroin in Cairo in 1916, via a Cairene chemist, and the punishment for smugglers and dealers at the time did not exceed a fine of one Egyptian pound or a week of imprisonment. The year 1929 was known as the year of doom in Egypt, when an official statistic revealed that half of the Egyptian population were heroin users.

Russell recounts that the first appearance of cocaine and heroin in Cairo was in 1916, via a Cairene chemist. The punishment for smugglers and traders at the time did not exceed a fine of one Egyptian pound or a week of imprisonment, until the white drug spread frighteningly fast to every part of the country. As a result, its punishment was increased to one year in prison and a fine of 100 pounds.

In 1928, the poor neighborhoods and slums of Cairo, specifically “Bulaq”, became endemic areas, after the “intravenous injection of heroin” became a common method used among drug users. As a result, deadly malaria spread in the Bulaq slums and the area became littered with corpses.

Russell recounts, “The investigations proved that malaria began and spread as a result of the injection needles and syringes that were previously used to treat malaria. The malaria infection would directly enter the bloodstream when the needles were inserted into the bodies of addicts.”

The year 1929 was known as the year of doom in Egypt, when an official statistic revealed that half of the Egyptian population (14 million at the time) were heroin users.

As a result of what happened in these areas, the penalty was raised to five years in prison along with a fine of 1,000 Egyptian pounds. The year 1929 was known as the year of doom in Egypt, when an official statistic revealed that half of the Egyptian population were heroin users. Russell writes, “When I conducted statistics on the number of users, I concluded that of the 14 million people — the total population of the country at the time — at least half were slaves to this drug. I saw that this was worthy of immediate action, and that it required the support of the Prime Minister. After meaningful talks with the prime minister, my request to form a central drug intelligence office was approved.”

Thomas Russell assumed the position of commandant of the Cairo police during a key period (1918), right on the cusp of the 1919 revolution. Although he was a witness and an active figure in these events, demonstrations, and uprisings as chief of the police at the time, his testimony to the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 came with great reluctance. He also dealt with it from a colonial point of view, where he spoke, with great grief, of the foreign employees and soldiers who died, and did not mention the Egyptian martyrs of the revolution.

Russell took pleasure in testing the Egyptian casualties to make sure that they were really dead. He used to drag his lit cigarette on their arms in order to reveal the truth. Despite this English arrogance, Russell’s memoirs are an important and rare documentation of half a century of Egyptian history.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!