Everyone knows that two of Syria’s post-Ottoman rulers were non-Syrians; King Faisal I (1918-1920) and President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1958-1961). But what of the four Lebanese figures who ruled Syria in its modern history; two from inside the Grand Serail (Government main office) of Damascus in Marjeh Square during the days of the French Mandate, and two from the General Staff Building during the Jalaa era, after the last French soldiers left.

Ahmad Nami Bey

A descendant of a prominent Circassian family that fled the Caucasus region and settled in Egypt at the turn of the 19th century, Ahmad Nami Bey was born in Beirut in 1878. His grandfather worked with Muhammad Ali Pasha in Cairo, and his father Fakhri Nami Bey came to Syria, where he was appointed governor of the Sanjak of Tripoli and then mayor of Beirut.

His son Ahmed studied at the Military College in Istanbul and worked as an officer in the Ottoman army before joining the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA).

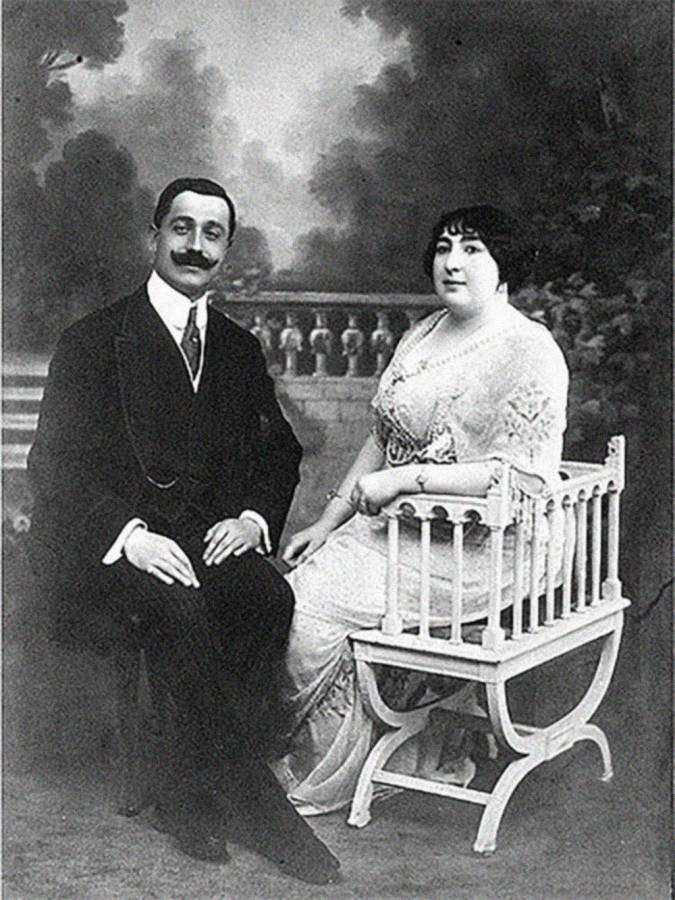

Ahmad Nami Bey with his wife

A young Ahmad met Princess Ayşe, the daughter of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and married her in June 1910, only 14 months after her father was dethroned. However the marriage did not last long, and after the divorce, he traveled to Switzerland to spend the years of World War I there, but kept the title “al-Damad”, which translates to “the son-in-law of the Sultan”.

He returned to Beirut after the French Mandate was imposed and the State of Greater Lebanon was established in 1920, and on April 20, 1926, he was named Prime Minister and President of Syria. This was at the height of the Great Syrian Revolt, following six months of the French bombing of Damascus, the burning of the Hamidiya market, and the destruction of a large part of the Midan neighborhood.

Everyone knows that two of Syria’s post-Ottoman rulers were non-Syrian; King Faisal I and President Abdel Nasser. But what of the four Lebanese-born men who ruled Syria in modern history?

He ruled Syria on his own, without a constitution or parliament, with no authority above his other than that of the French High Commissioner in Beirut. In his first government, al-Damad worked with key figures affiliated with the National Bloc, bringing Fares al-Khoury as Minister of Education, Lutfi al-Haffar as Minister of Trade, and Hama’s distinguished Husni al-Barazi as Interior Minister. This national formation covered Damad’s weak record when it came to public affairs, as he didn’t have any notable appearances and hadn’t made much of an impression before coming to power in Syria. He did not even hold a Syrian passport. He also set an ambitious agenda for his government, at the forefront of which was issuing a general amnesty for all political prisoners, along with enacting a new constitution for the country and having Syria join the League of Nations. He demanded that the French Mandate be turned into a treaty with France, where Syria would be treated as an ally country, and not an inferior nation or a colony of the French Republic.

But his rule suffered from a number of back-to-back blows, the first of which was the arrest of nationalist ministers on charges of collaborating with the Ghouta rebels of Damascus, and the French refusal to stop military operations in the Jabal al-Druze region. President Nami was unable to stand up to the French and couldn’t win back the favor of the nationalists either following the arrest of the three ministers, and was ultimately forced to resign on February 8, 1928.

He then returned to Beirut, and never went back to Syria. He was offered to return to power in Damascus in 1941, but the National Bloc stood in his way. He traveled to France and worked as a professor and lecturer at the Sorbonne until his death at the age of 88 in 1966.

The Lebanese Ahmad Nami Bey ruled Syria alone in 1926, without a constitution or parliament, with no authority above his other than that of the French High Commissioner in Beirut

Bahij Bey Al-Khatib

In the Lebanese village of Chehime in the Chouf district, Bahij al-Khatib was born in the year 1885. He studied at the Souk el-Gharb schools and later at the American University of Beirut AUB. He went to Damascus at the age of 33 in 1918 to work with Emir Faisal bin Al-Hussein, the new ruler of Syria after the fall of the Ottoman rule. He was appointed clerk in the office of Emir Faisal and then in the Syrian Interior Ministry during the reign of Minister Rida Solh, a Lebanese figure like him and the father of President Riad Al Solh.

After the demise of the Faisal rule and with the imposed French mandate, al-Khatib remained in Syria and obtained Syrian citizenship during the reign of Ahmad Nami, who appointed his brother, poet Fouad al-Khatib, director of his office in Damascus. Al-Khatib worked in silence and refused to join any political party, and in February 1928, he was named director of the Syrian Police.

Bahij al-Khatib improved the police force and introduced new branches into it for night watches (guards) and traffic management. He also established a system for archiving and keeping records of criminals and those with prior offenses. The National Bloc accused him of tampering with the parliamentary elections, and staged a large demonstration against him on April 12, 1928, which al-Khatib himself dispersed. It was said that he fired shots at the demonstrators that day and killed six of them.

Journalist Najib al-Rayyes wrote an article in the al-Qabas newspaper, addressing Bahij al-Khatib with the words: “I wore tiger skin during the election week, and I have lived in this city for ten years wearing that of a fox. You are only proficient in flattery, and only know cunning yellow (fake) smiles.” He then concluded by saying: “To Chehime, Bahij al-Khatib,” (in reference to his Lebanese origins, replacing the word ‘hell’ with ‘Chehime’). Al-Khatib responded by closing the al-Qabas newspaper down and arresting its owner.

The final blow for him was the arrest of a number of Damascene women when they went out in a demonstration against the French, which greatly inconvenienced the French Mandate authority, putting it in a tight spot and forcing it to abandon him in November of 1934.

Bahij al-Khatib returned to the limelight at the end of 1937, when he was appointed as governor of Jabal al-Druze for a period of three months. In July 1939, following the resignation of President Hashim al-Atassi, he was appointed head of a government of non-partisan specialists, called the Cabinet or Council of Directors. His government was supposed to be a transitional government with only one goal, which is to supervise the upcoming parliamentary elections, but the outbreak of World War II extended its life and kept it in power until 1941.

Al-Khatib ruled Syria with iron and fire, and struck the National Bloc at its very core, which led to a failed assassination attempt in the summer of 1939. A number of Hama revolutionaries stood behind the attempt, led by young lawyer Akram al-Hourani. During his reign, the World War II began, and al-Khatib took charge of prosecuting all those convicted of Nazi funding. Meanwhile, nationalist leader Abd al-Rahman al-Shahbandar was assassinated and fingers began pointing towards the National Bloc itself. Investigation records stated that al-Khatib met with the perpetrators at the police headquarters, and ordered that they’d be tortured so they would say that the assassination order came from former Prime Minister Jamil Mardam Bey. After Mardam Bey and his companions were found innocent, France dismissed al-Khatib from his post in April 1941.

He returned to the forefront once again as the Minister of Interior in September of 1941 in the government of Prime Minister Hassan al-Hakim. In April 1942, he was named Secretary-General of the Interior Ministry until October 13, 1943, the date that marked his appointment as governor of the city of Damascus. This was during the era of President Shukri al-Quwatli, but the decision to appoint him drew a wave of criticism, so the president dismissed him less than a week later. Al-Khatib realized after that that his chances of returning to power had become almost non-existent, so he decided to retire from political work and return to his hometown of Chehime, on the eve of the French evacuation from Syria in 1946.

After having witnessed all the military coups that swept through Syria and the civil war that erupted in Lebanon in 1975, Bahij al-Khatib died in Lebanon in 1981 at the age of 96.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!