According to the United Nations, violence against women and girls is one of the most widespread violations of human rights in the world, estimated one in three women experience sexual or physical violence in her lifetime. For female journalists, the situation is even worse, with one in two female journalists experiencing gender-based violence, such as sexual harassment, mental abuse and online trolling, according to a study, Conducted in 2017 by the International Federation of Journalists.

Hence, gender-based violence against women journalists is a global epidemic, which women journalists experience as a daily routine to varying degrees in different countries of the world, especially after the Corona pandemic. “Women no longer feel safe, either online or offline, given the widespread impunity for perpetrators of gender-based violence”, said the UN special rapporteur, Dubravka Simonovic, who prepared a detailed report on violence against women journalists, published May 2020.

In Morocco, women journalists suffer from various forms of violence and discrimination, leaving them with physical and moral injuries, making it difficult for them to carry out their work. In this context, my investigative report aimed to shed light on gender-based violence against women in the country, including physical violence, sexual and economic violence, and online violence, providing quantitative results and analyzes on the topic, in addition to the stories of some cases who they reveal their experience of gender violence for the first time.

General quantitative results on gender-based violence against women journalists in Morocco

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to harmful acts that target an individual based on their gender. It is rooted in gender inequality. “It is an umbrella term for any harmful action against a person's will, having reference to the socially constructed differences between males and females. It includes acts that inflict physical, psychological or sexual harm, or threats of such acts, or coercion against a person's liberty” the United Nations Fund defines.

It is also called gender-based violence, and it may also affect men, but since most of the recorded cases fall in the category of women, it has become widely seen as an issue related to women.

Although Morocco has made great progress in the area of women's rights since the beginning of the millennium, it still ranks 137 out of 149 countries according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2018, due to social disparity between the sexes, which in turn generates the phenomena of sexism.

It’s obvious when it comes to female journalists in the country, who experience different forms of gender-based violence, as the results of this investigative report, where the journalist borrowed social research methods, such as survey forms and qualitative interviews. The journalist does not claim that this report represents scientific research, but it provides a journalistic insight into the gender-based violence issue in Morocco. Here are its most prominent results.

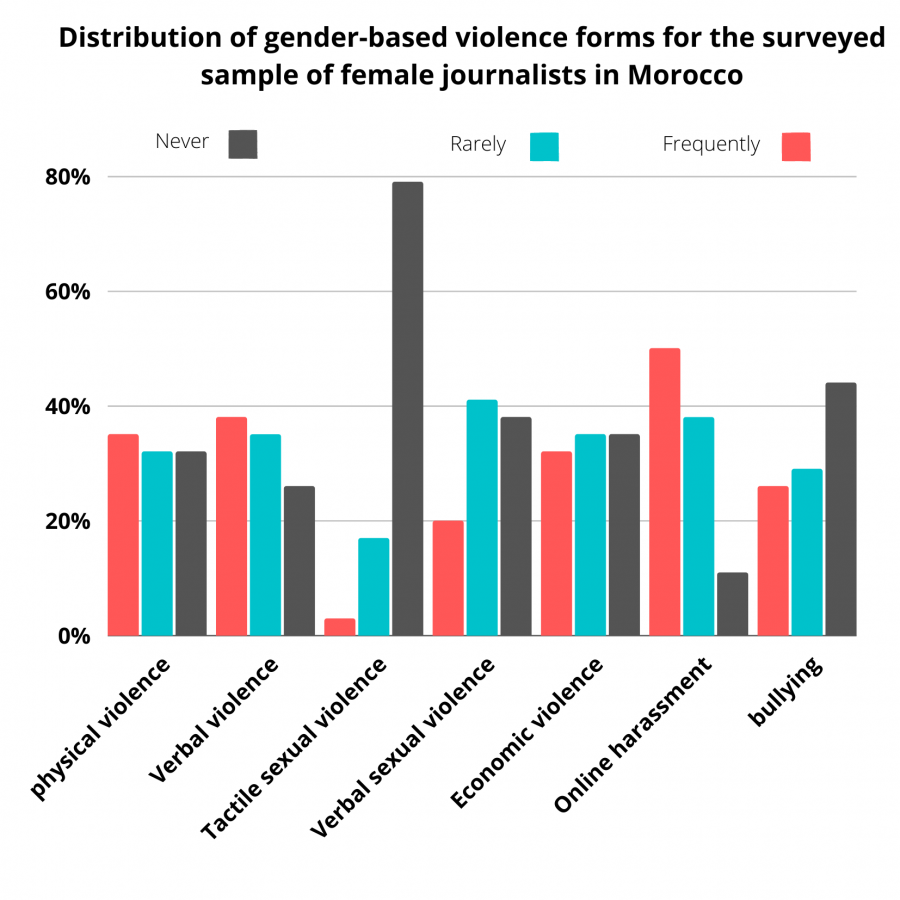

The results showed that 74% of the surveyed sample was subjected to one or more forms of gender-based violence during the past two years, a result almost similar to the result of violence against women journalists reports around the world.

Online harassment has emerged strongly, as 50% of female journalists reported that they were frequently harassed online, and 38% sometimes. Then verbal violence, as 38% of the surveyed sample experienced this type of violence repeatedly, and 35% sometimes.

While tactile sexual violence and physical violence - which requires contact in reality- are uncommon compared to other forms of violence, which indicates that social media platforms have provided a fertile environment for gender-based violence against women journalists in Morocco.

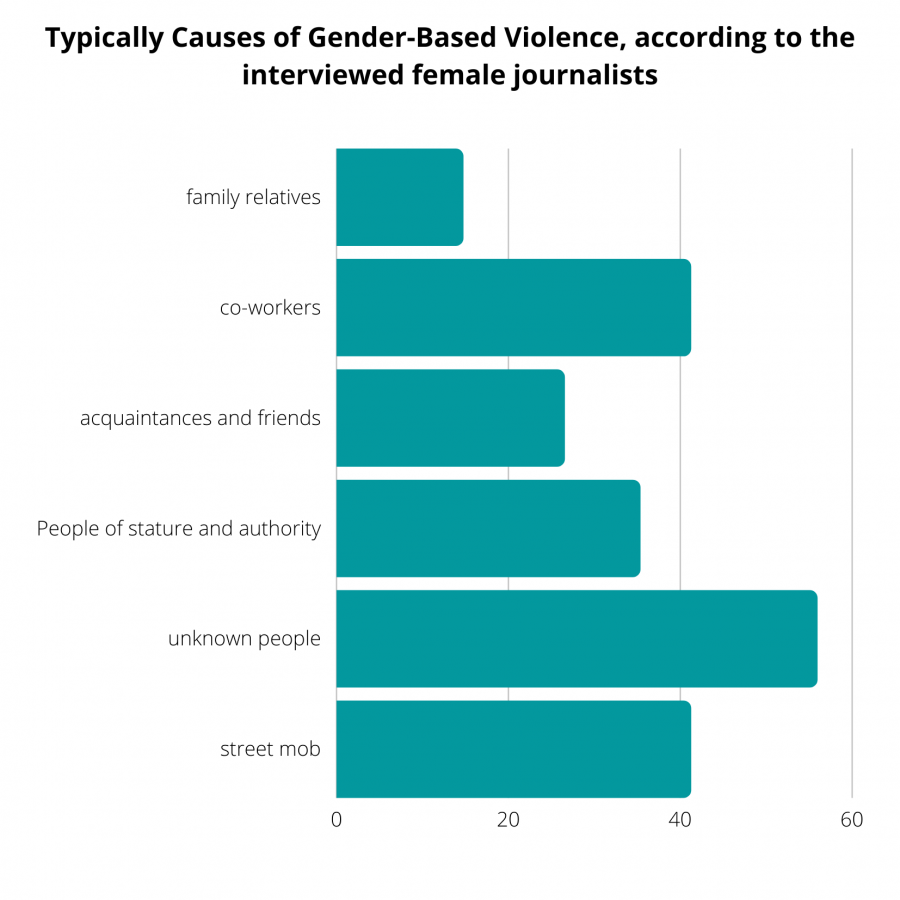

On the other hand, the results of the survey indicate that the majority of those responsible for gender-based violence experienced by female journalists surveyed are unknown persons at 56%, followed by the street mobs at 41%, the same percentage of colleagues at work, and then 35% of violence against female journalists come from those with power and influence.

Acquaintances and friends, as well as family relatives, are not excluded, albeit to a lesser degree, which indicates that gender violence against women journalists is somewhat rooted in the society’s culture.

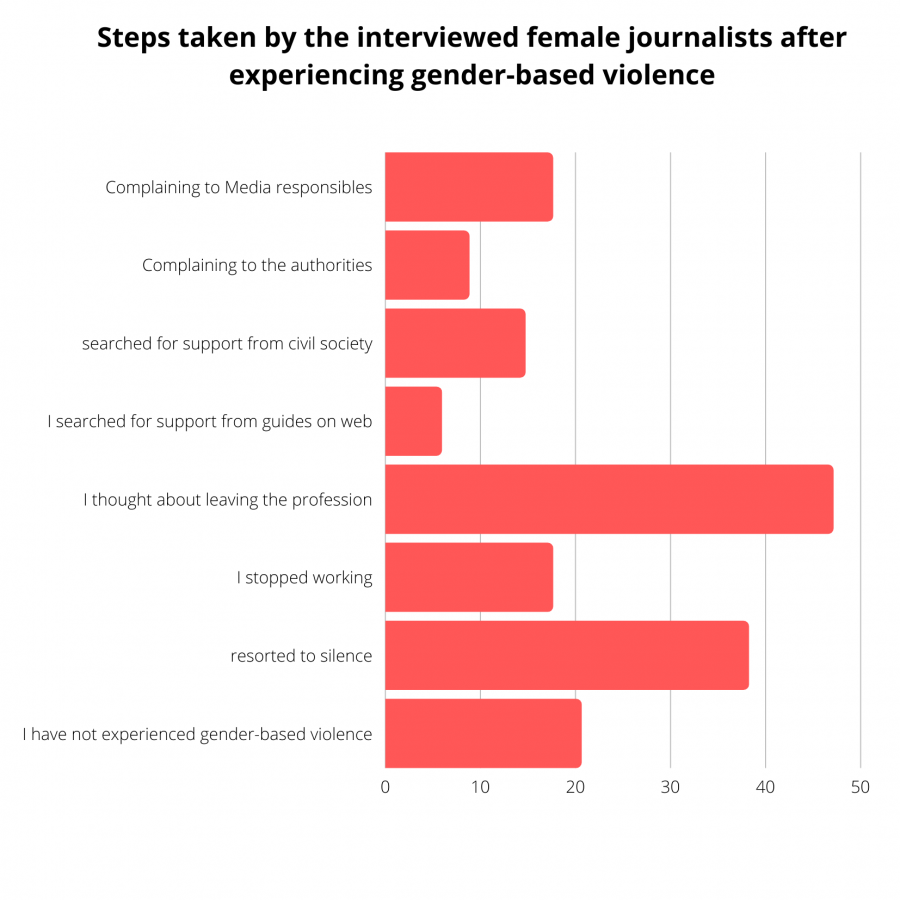

When we asked female journalists about the steps they took after experiencing gender-based violence, the majority responded that they considered leaving the profession, or resorted to silence. While only 9% filed a complaint with the official authorities.

Stories of female journalists with gender violence

To understand more about gender violence against female journalists, we conducted qualitative interviews with some cases, related to different forms of gender-based violence: economic violence, sexual violence, online violence, and physical violence.

The general result was that most of them showed a strong willingness to continue the path of journalism despite gender obstacles, and they were proud to be journalists. They also learned from their harsh experiences in the field how to deal subjectively with the problems of gender-based violence.

1. Sexual violence

Sexual violence refers to sexual assault, including rape and sexual harassment, it’s when a sexual act is performed or attempted by coercion or force, without the consent of the other party. Sexual violence may also take a verbal form that appears in sexual comments and remarks, which are not welcome by the other party, usually related to the body and dress.

Like all women, female journalists, , may be exposed to different forms of sexual violence, whether on the street or in the workplace. According to the poll conducted by the journalist, female journalists in Morocco didn’t confront sexual violence on the ground.

This may be a good sign that the situation of female journalists in Morocco is improving, or it may be the issue is still “taboo” due to fear from stigma on the victim and her family, especially it was difficult to persuade some of those who are subjected to sexual violence to talk, unlike other forms of violence based on Gender, as it was easy for female journalists to narrate their experience.

Maryam (a pseudonym) is one of the young female journalists who have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. “I was repeatedly sexually harassed by a person in charge of the media organization in which I work,” she said. “It all started when I had a job interview, and got accepted. After a short time, he began to throw at me some hints about my clothes and hairstyle, during and outside work hours, and sometimes he tried to single me out, get close to me and touch me, but I always ignored his suggestive messages, and avoided being alone with him.”

Maryam added, “He knew that I was in dire need of work, and he was taking advantage of that to get close to me, but I refused to get out with him, which put me in a permanent conflict with him. It affected me a lot at the time; I was constantly crying and deciding every day to stop working, but I remembered my urgent need for the job, I was relieved only when that person left the media. After a while, he contacted and apologized to me after realizing his mistake and stopping the harassment”.

“Women journalists can confront situations where they have to choose between continuing work or accepting harassment, especially from those who have authority over them. In face of lack of job opportunities, some of them are forced to continue either by being patient and not giving up, or by responding to the person to continue work. But I recommend not to surrender, and if necessary, to report the harassed person judicially”, Maryam says.

2. Economic violence

It means gender-based economic violence and financial inequities that affect women, such as deprivation of work, and lower wages compared to men. An International Monetary Fund study indicates that Morocco is currently losing a large share of income due to gender gaps in the market. Gender segregation currently costs Morocco about 46% of per capita income, compared to countries where women are more present in markets. “If women were working as many as men in Morocco today, the per capita income could be close to 50% higher than it is now”, The International Monetary Fund stated.

Female journalists in Morocco may be subjected to economic discrimination, some being paid less than their male peers, while others are deprived of their financial rights. 32% of female journalists surveyed had repeatedly experienced economic violence.

Salma (a pseudonym) is one of those who have been subjected to financial mistreatment. “During my first experience working in the press, I have worked for a very poor wage, as I was convinced that the institution was in its infancy and the salary would gradually improve in future, but the year passed without any change. More than that, additional tasks were added to my duty, which I considered only cooperation in the beginning, before becoming obligated to do. Every time I asked the manager to increase my salary, I was met with justifications and promises, until I decided to change the workplace.”

Salma continues: “Since then, I decided to be decisive from the beginning about the wage issue, which made it difficult for me to find a new job. It took months of research to find one. However, the same experience was repeated again. So, I had to finish the work again in less than three months, and start over the journey of searching for a job. Without my family encouragement to realize my dream of working as a journalist, despite their need for money, I would have quit this field and chose another job.”

Salma concludes, “But I learned from that experience not to trust any manager who narrates his sweet speeches to me, as I learned to do my work only according to what was agreed upon at the beginning, and not doing other work that does not fall within the agreement, even if I was asked to do so. Which was annoying to the managers, so they tracked my lapses, reprimand, and warn to be expelled.”

3. Online violence

While the digital age has opened up new opportunities for women to express and publish, especially for female journalists, it has also provided a platform for new forms of online violence, including online bullying, cyberstalking, sexual blackmail, phishing, revenge porn, espionage, and hacking.

Journalists are exposed to cyber violence because of their publications on corruption, politics and human rights violations, to silencing them. Women journalists remain more likely to receive assault comments and sexual attacks focused on appearance.

That form of gender-based violence was the most present according to the survey.

Wafaa (a pseudonym) told her story about online bullying: “After I shared a reportage about a gender issue on my Facebook page, I was shocked by a wave of abusive comments by unknown interactors of both sexes. They started making fun of me, and intrusive my personal things into the subject, away from the content, after they broke into my account and my pictures.”

“I regretted a little bit about sharing the link, despite the encouragement I received from many, but these negative, offensive comments remained stuck in my mind, as they brutally attacked my person, my body and my face, which prompted me to avoid working on such topics for a while. I no longer share all my works on social media. I only select the normal ones”, Wafaa said.

As for Khadija (a pseudonym), she has repeatedly experienced online harassment. “In the context of journalism, I usually give my phone number to some people, such as association and human rights activists, in order to take statements or inquire about a case I work on. Once I gave my phone to a person source. He began to provide me some news, and we communicate constantly until we became friends, we talk among ourselves without affection respectfully, until he told me one day that he liked me and went on about it. So I told him to keep the relationship as it was. He kept making sexual innuendos, till one day he sent me indecent pictures of himself!”.

"I was shocked, I never expected this situation with this particular person. I warned him to stop his sexual fantasies”, Khadija said. However, she does not believe that journalism is a dangerous profession for women in Morocco. “On the contrary, sometimes, when others know that I am a journalist, they treat me more carefully, and I really feel that it is the fourth authority and that I am in a position of strength and protection”, Khadija explained.

4. Physical violence

Physical violence refers to an intentional act that causes injury or trauma through physical contact, or the threat to do so, with or without a weapon that may threaten physical safety. In the journalism, female journalists, like all journalists, may be subjected to physical attacks, especially when covering tense events or neighborhoods’ chaos. 35% of female journalists have repeatedly experienced physical violence, according to my survey.

Loubna (a pseudonym) has experienced physical violence because of her work. “I was subjected to many harassments in streets while carrying out my duty, as a photojournalist. Once, a mob person in the street demanded me my phone number. I refused, then he forced me to stand against my will, and grabbed my hand. I screamed for help, which prompted some citizens to intervene for help. In the following days, I avoided going out to work, and I refused to work outside the headquarters unless accompanied by a colleague of mine. I also avoided crossing that place for fear of running into that street person.”

“I did not file any complaint. When I told my co-workers, they advised me to go to the police station without hesitation whenever I confront a similar problem”, Loubna mentioned.

Loubna draws attention to the fact that, sometimes, woman journalist cannot venture alone at night, or enter some chaotic neighborhoods, to carry out a journalistic assignment. She advises her female colleagues to "go to the nearest police station and file a complaint when experiencing physical violence, while being careful at work and avoiding suspicious places".

The origins of gender-based violence against women

Understanding gender-based violence and its causes is critical, according to a guide of The United Nations Population Fund, to enact appropriate responses to the problem, addressing it from the roots and not just superficially.

The gender-based violence issue can be understood through three aspects, which we explain in the following:

1. Interpretations of social theories

To understand gender-based violence against women journalists, and women in general, one must dig deep into the roots of gender inequality, “Gender-based violence is a phenomenon deeply rooted in gender inequality, and remains one of the most prominent human rights violations in all societies”, confirmed by the European Institute for Gender Equality. Thus, gender inequality is strongly implicated in gender-based violence against women.

The British sociologist, Anthony Giddens, explains the issue in his book “Sociology”, saying “identities gender naturally built and socially, but differences gender are rarely neutral, in almost all societies represent a form of stratification and social gradient, which is a key factor in forming opportunities and choices of life that faced by individuals and groups”.

He adds, “Although men’s roles differ from one culture to another, we do not know of any culture in which women have more power than men. Women in almost all cultures bear the primary responsibility for raising children and household chores, while men provide for the family's livelihood. The prevailing division of labor between the sexes has resulted in inequality between women and men in terms of positions, prestige, power and wealth”.

Thus, gender inequality arose, through the division of the social roles based on gender differences in the first human societies, with time a socio-cultural power of men over women was formed according to that division system, which was passed down from generation to generation through socialization. “Despite the progress that women have made to varying degrees in most of the world, gender differences are still the basis of social inequality,” says Anthony Giddens.

While the radical feminist school kicks off from the idea that men are responsible for the exploitation of women and they are the beneficiaries at the same time from this situation. They believe there is systematic domination of males over females embedded in the political and social structures of society, and there is no choice but to overthrow those structures, according to feminist movements.

Another hand, Analytical Psychologist Sigmund Freud And the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that inequality between sexes is rooted in our inherent view of sex and sexual relationship, in which the idea of the man’s superiority (the phallus) over the woman (the recipient of the phallus) is stored almost instinctively, and from this closed view the inequality of sexes stems.

No matter how these interpretations about the origins of gender inequality are different, they all affirm that violence against women arises from unequal power relations between men and women that are rooted in societies’ culture. So a fertile environment arises for gender-based violence to form, as a “natural” part of women’s life.

As such, female journalists are subjected to sexism, as they are expected to fit gender roles and image, like other women, especially when they passe gender inequality rules in their journalistic work.

2. The role of local factors

Women’s status has witnessed a great improvement that began since the beginning of the twentieth century in the Western world, but the winds of modernization did not reach the societies of North Africa and the Middle East in a large and comprehensive manner except in recent decades. The patriarchal culture is deeply rooted in society.

It mentions In this context, the United Nations Fund stated that “social beliefs and behaviors in this region still build perceptions of women and girls, as being less than men and subservient. Creating a culture and environment in which it is easy to harm women. This dependent and subordinate position is often reinforced with the help of various existing social and cultural institutions, such as educational, religious and legal institutions».

It is not surprising that these societies in North Africa and the Middle East know a noticeable gap in the issue of gender equality, according to World Economic Forum Report 2018. Although the region has made a significant progress in the field of women's rights since the beginning of the current millennium, the prevailing social perceptions still maintain the traditional division of roles.

On the other hand, it must be clarified that feminist studies are dominated by a Western view, thanks to the geographical context in which they were conducted. Therefore, projecting those views on the Arab region may be insufficient to explain gender-based violence in North Africa and the Middle East, as other local factors may play out a role in this issue, such as poverty, political tyranny, economic pressure and sexual repression, where men are on the front lines in the face of all these pressures.

However, the university professor and researcher in sociology Ahmed Al-Mutamassik does not agree with men who export violence against women, and he says in his talk to us: “We should not hold women responsibility for our problems and economic pressures, which have exacerbated after the Corona crisis, or make it a scapegoat. Rather, the man must learn to deal with his problems and the circumstances he is going through. He needs to take responsibility as an adult and believer equality”.

The researcher explains more, saying, “Violence against women is mainly due to the patriarchal mentality that exists in Morocco and the whole Mediterranean region. The mentality is rooted and implicit socially of both men and women, as it requires men to prove their masculinity in front of society through practicing violence against women and children. The culture considers violence against women and children is normal and legitimate, when it is not».

Because female journalists are part of these societies, social norms and gender stereotypes continue to inhibit women’s work in this profession on an equal basis with men, as journalism in some cultural and social contexts is considered a profession unsuitable for women and contrary to the values of marriage or family, although recent years have witnessed an increase in the number of women choosing journalism as a profession in North Africa.

3. Internet as a breeding ground for gender-based violence

Attacks against journalists on the Internet are considered a routine phenomenon, due to the press reports they publish, which may not appeal to some people or organizers. However, women journalists are more subjected to violence on the Internet, which makes the latter an important factor in fueling gender-based violence.

In 2020, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) published a global survey to assess the scope and impacts of online violence targeting women journalists, it is the most comprehensive and geographically diverse survey ever conducted on the topic, with 714 women journalists from 113 countries.

73% of women journalists surveyed by the International Center for Journalists and UNESCO said they had experienced a wide range of online violence, including sexual assault, physical violence, verbal abuse, harassment, cyber-attacks and disinformation designed to silence journalists.

“Feels like a low-intensity, continuous war, in which women are targeted online the same way they are in cyberwars,” Finnish journalist Jessica Arrow said for the research survey team.

The UNESCO/ICJ study concluded that “social media platforms, particularly Facebook, are a major contributor to online violence against women journalists,” as social media companies lack gender-sensitive solutions, rapid response capacity in all Languages.

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated online violence against female journalists due to increased online uptake, with 16% of female journalists interviewed saying online abuse and harassment was “much worse than usual,” according to another global survey, conducted by the International Center for Journalism and Justice and the Tao Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University as part of the Journalism and Epidemic Project.

Female journalists who are targeted usually respond to violence via the Internet, by activating self-censorship on their publications on social networks, as Wafaa previously told us, who carefully selects her publications before publishing them on Facebook, after being subjected to the hard experience of online bullying. While some female journalists withdraw completely from all social media, and avoid public sharing their stories, which may put a hidden pressure on press freedom and expression.

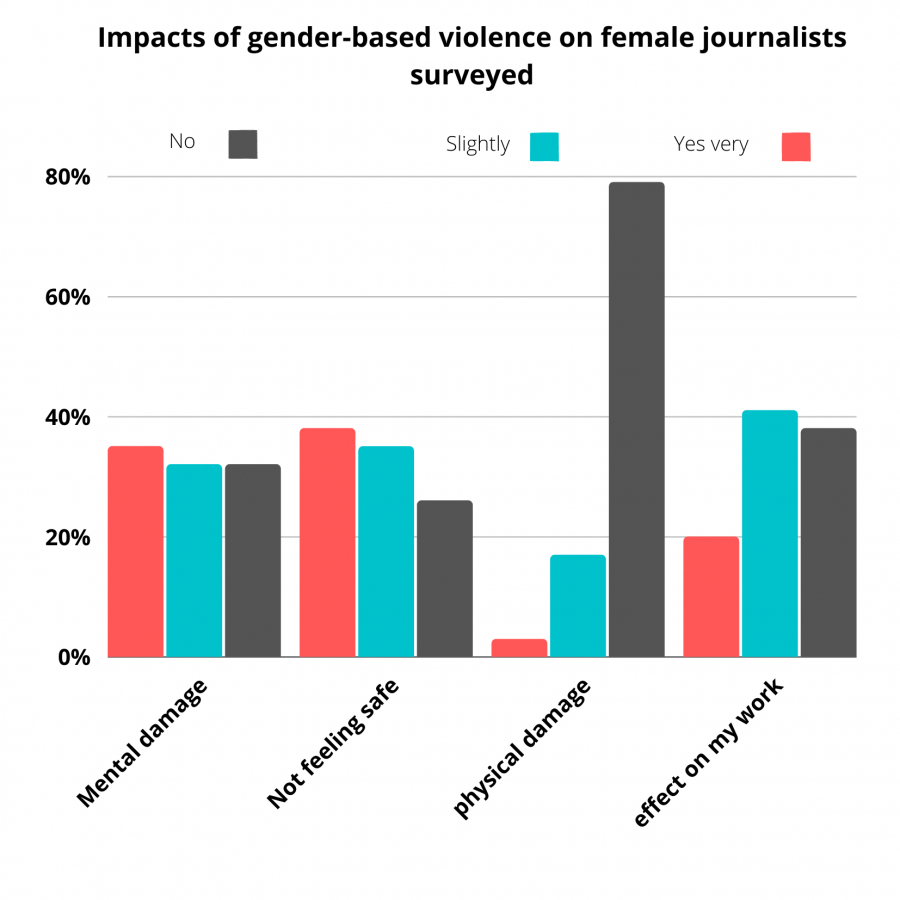

Effects of gender violence on female journalists

Many women working in the field of journalism face daily various forms of gender-based violence, following them from work to the home, and invading their professional and private spaces. Sometimes the abuse is brutal and merciless.

Attacks on female journalists lead to psychological and physical harm, self-censorship, or to withdraw completely from the press, which greatly affects freedom of expression and diversity in media, reducing the number of women in newsrooms.

In our survey, we asked female respondents about the damage they sustained after being subjected to gender-based violence. 47% of the sample answered that they did not feel safe, 35% reported mental harm, and 26% said that what they were exposed to had an impact on their journalistic work. While 47% said they thought about leaving journalism after experiencing gender-based violence.

Female journalists who report sexual assault may also be exposed to cultural stigma, therefore many of them often avoid reporting out of fear for their families’ reputation, or for fear of being seen as a threat by colleagues, which could deprive them of future opportunities.

Based on the UNESCO/ICJ Global Survey on online violence against women journalists’ results, 20% of those who have confronted threats and abuse online, report that they have been directly attacked afterward. In addition, 17% of female journalists participating in the survey said they practice self-censorship due to online violence.

Psychological stress was the most prominent damage experienced by female journalists who were subjected to gender-based violence, whether in the poll I conducted or the UNESCO survey, which adds a heavy mental burden to women in the profession, which needs a lot of serenity and energy.

This scourge of gender-based violence threatens not only the women journalist’s safety, but also the freedom of press and expression, as women journalists often resort to avoidance strategies in response to attacks, including picking at the topics they work on, choosing stories to share with the public, and even thinking about Quit journalism, or literally withdraw from it, undermining accountability journalism, which is a vital necessity for societies.

How can the dilemma of gender violence against women journalists be resolved?

The issue of gender-based violence against women journalists has begun to be highlighted in several recent UN and UNESCO resolutions. The UN rapporteur, Dubravka Simonovic, had prepared a report on violence against women journalists last year, addressing the challenges facing women journalists, as well as their causes, and made recommendations to states and other stakeholders on how to address this issue, which has been exacerbated in the context of the coronavirus pandemic.

As such, the Special Rapporteur's efforts seek to lay the groundwork for States to establish an appropriate human rights framework on this issue, including developing policies or strategies to ensure the protection of women journalists.

We reached out to the UN Department of UNESCO to understand ongoing solutions to ensuring the safety of women journalists around the world, and addressing gender-specific threats. “In order to tackle the gender-specific threats to the safety of women journalists online and offline, responses need to be tailored to relevant stakeholders, such as governments, media organisations, civil society or online platforms”, Saorla McCabe, Deputy Secretary of the International Program for the Development of Communication at UNESCO, told us.

The UNESCO adviser explains: “Governments should develop effective prevention, protection, monitoring and response mechanism to address violence against women journalists, both online and offline. Furthermore, tackling violence against women journalists needs to be anchored in broader efforts to improve gender equality and the rights of women”.

Regarding the growing problem of online violence against women journalists, she said, “governments can ensure that laws and rights designed to protect women journalists offline are applied equally online”, she said.

“Online Platforms need to strengthen their efforts in addressing the growing issue of online violence against women journalists. Amongst others, online platforms could define more effective policies and procedures for detecting and penalizing repeat offenders and stop the same abusers assuming new online identities after temporary suspensions or permanent bans”, Saorla McCabe recommended. “They should create more effective abuse reporting tools that support local languages and are sensitive to local cultural norms, and ensure more transparency with regard to how they respond to reports of harassment”.

At the local level, Morocco has made remarkable progress in gender equality, after unremitting efforts in politics, laws, media and civil society since the beginning of the current millennium. However, much remains to be done, so that the presence of women in journalism be consistent with their contribution to the society development.

In this context, a group of civil society organizations is active in combating sexual violence, including the network of the Association Anjad Against Gender Violence, whose manager Najia Tazarout said, “We provide listening services to women victims of gender-based violence, including female journalists, with the help of psychological and social support specialists”.

“We also provide free legal guidance, accompaniment and support to battered women in difficult situations. In addition to our contribution to advocating for changing some laws and achieving equality between men and women”.

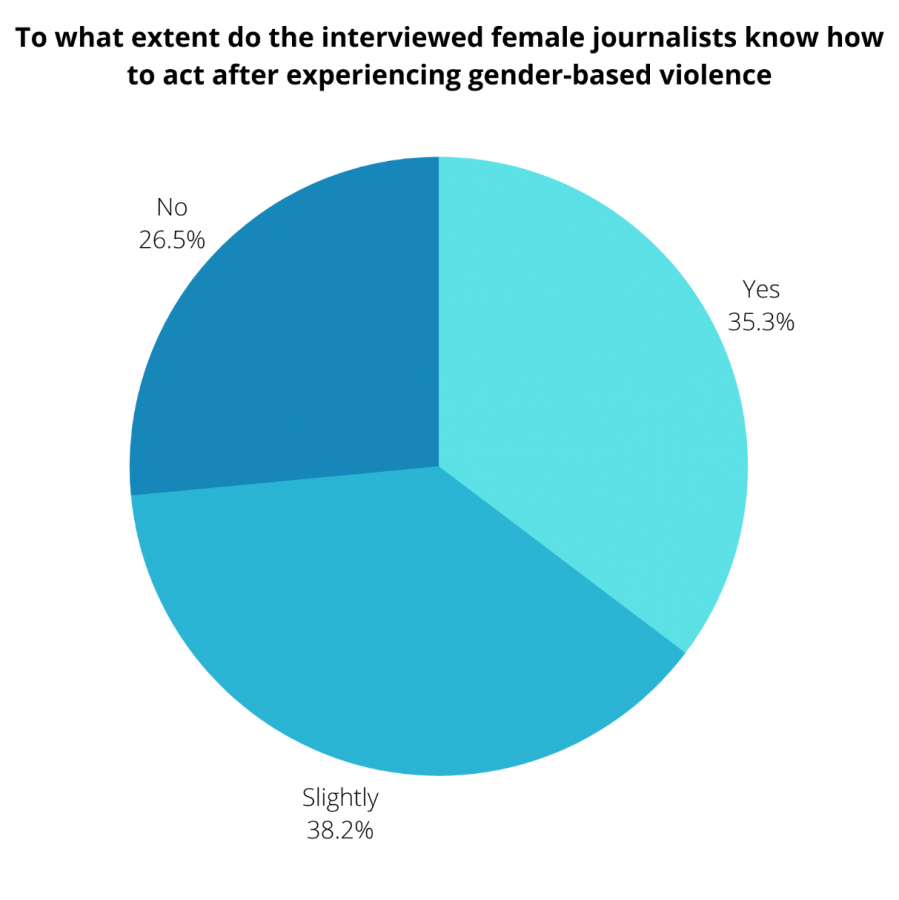

The lack of Moroccan female journalists surveyed in the knowledge necessary to restore their rights and mental well-being in gender-based violence events was remarkable, as 35% said they did not know how to deal with the matter, while 38% expressed little knowledge in this regard.

This raises the need to make useful resources available to female journalists throughout the day, in order to use them in a time of need in connection with gender-based violence. International media organizations are dedicating guidelines and resources to combating gender-based violence against women journalists, including:

- Online Violence Response Center was launched newly by the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF) and the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ). The center provides various resources in one place, to provide support, assistance and guidance to victims of attacks via the Internet. For female journalists, the orange “emergency assistance” button can be pressed in case they need emergency assistance.

- The United Nations Population Fund has produced a comprehensive guide On how to cover GBV topics, to help journalists and media platforms.

- Launched recently by Thomson Reuters and the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF) a practical guidance manual on the safety of female journalists.

- The International Federation of Journalists' website is a set of guidance resources For the safety of women journalists, they also offers ways to help.

- In 2020, Freedom of journalism published a comprehensive guide on the safety of female journalists, directed to civil, media and political organisations.

- Also, there are relevant official centers in each country, in addition to civil society organizations working on violence against women that assist in cases of gender-based violence.

It remains to point out that some governments - according to press organizations - use “combating gender-based violence” not to enhance the role of press freedom as it is supposed, but as a new tactic to silence journalism and punish outspoken journalists who report on corruption and abuses of power and hold those in power accountable , “After being accused of sexual crimes, as happened with the investigative journalist Omar Radi and journalist Suleiman Raissouni, who are currently in prison in Morocco”, according to the International Committee for the Protection of journalists (CPJ).

However, gender violence is a local and global phenomenon, affecting women in general, including women journalists, who may bear the burden of gender violence, in addition to the attacks and intimidation that the free press suffers at present, by governments, mafias and financial lobbies in many regions of the world.

Sources:

2- IFJ survey: One in two women suffer gender-based violence at work

3- Combating violence against women

4- Preparing global reports on gender-based violence

5- «Sociology» by Giddens Anthony

6- Freud's Perspective on Women

7- The 2018 World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report

8- Online violence Against Women Journalists

9- The Committee to Protect Journalists

10. Welcome to the Online Violence Response Hub

*This report was produced with the support of «Justice for Journalists Foundation».

*Illustrations including the cover show gender violence against women - Credit: Khalid Bencherif

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!