Without any complications, nations emerged and were established when a group of people inhabiting a particular land decided to determine who would manage their affairs and facilitate their daily lives. The wealth and resources of any state are the property of its citizens, not the property of any authority. This is the hard enduring truth that has been universally recognized and accepted by all countries, and which I didn’t think I would have to remind myself of in the 21st century.

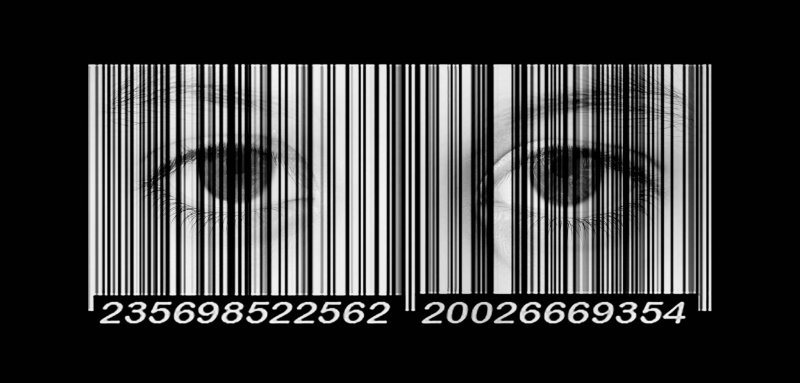

I was forced to do so when I found myself in a country that doesn’t treat us as the original owners of its wealth, but rather as “customers” who must pay for every service that’s provided to them. This was evident in the decision to cancel the state-issued ration cards for those who’ve been newly married. Within just a few years, subsidies for fuel and electricity have been lifted, and services became a “commodity” that we pay for on a monthly basis. We also pay for the right to pass through new roads, for treatment in public hospitals, and even pay fees for a student to enter and have his exam. All of this assured me that this is the current policy of the state, and that speaking of them as mere temporary measures for comprehensive economic reform was nothing more than a form of deception, even though the funding of these services is supposed to come from the resources in the treasury, which are our resources as citizens in the first place.

In my country, I became a “customer” who pays for all kinds of services, perhaps I would have accepted this if it was accompanied by political and economic openness, or if I could monitor where the money that I pay goes

To be fair, this “customer” model is not exclusive to Egypt, and although there is no conflict between being a citizen, obtaining your freedom, and taking part in the decision-making process, a few countries did this, but the majority, in my opinion, dealt with their citizens through one of two models:

The first is the “citizen” model, in which the state takes charge of providing housing, food, health and social insurance at a symbolic fee, in return for depriving citizens of any oversight or political participation in power. In Egypt, we experienced this with the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and it continues to this day in the countries of the Gulf, no matter what is said about the “democratic” constitutions and processes that do not change a thing at the core of governing.

The second type is the “customer” model. This system means that the state is not committed towards its citizens with anything. All services and goods, including health, education, roads and fuel, are paid for, whether through taxes or cash, without any aid or support, but in return, there are political freedoms that allow for peaceful political discourse and transfer of power, in addition to freedom of belief and opinion as well as the establishment of parties. And of course the economic freedom that is represented in the private sector can compete with these countries when it comes to providing services and goods to offer the best at the lowest possible price, in the hopes of conquering the market.

This model is the basis of the Western tagline “No tax without participation”, simply put, if the state won’t provide anything and own the right to services, then we must participate to know where our money is being spent? And how? And what is the best way to spend it? This task is carried out by the press, by opposition parties, and by civil society institutions in full independence.

As for Egypt, during the Nasser period it had adopted the “citizen” model, then it began to shift to the second option during the era of the late President Anwar el-Sadat, when he began a policy of economic openness in the mid 1970s, followed by an attempt to lift subsidies on some food commodities, resulting in what came to be known as the “bread riots” of 1977, which in turn led to the reversal of those decisions.

During the era of former President Mubarak — whose rule I lived under for two decades — the state’s policy did not change when it came to lifting support off subsidies. It was a weak justification for the security and political oppression in the Mubarak era, that was meant to make us feel like we are still citizens that the state is committed to providing basic needs for, in exchange for giving up any ideas regarding people’s rights and liberties. This however did not work on a generation that realized that true citizenship is inseparable from freedom, which is what I and others sought to attain when we took to the streets on January 25, 2011.

Even though I’m one of those who pay taxes that are deducted from my salary every month, such taxes are increased every year under many pretexts, this did not prevent me from completely losing my sense of citizenship in recent years.

The state completely lifted any support that it provides to citizens, and this is how I became a “customer” in my own country who pays for all kinds of services, and perhaps I would have accepted this if it was accompanied by political and economic openness, and if I had the right to monitor the fate of the money that I pay from my own pocket, as is the case with all countries that follow this model.

Egypt completely lifted any support that it provides to citizens, this is how I became a “customer” who pays for all kinds of services, perhaps I would have accepted this if it was accompanied by political and economic openness

But what happened is that I didn’t even get any of the benefits or advantages of the “customer” model, for there’s no complete freedom in what I say and think, and there is no strong economic competition, and of course, it is not allowed to monitor the money I pay from my pocket, proving that Egypt, when it wanted to turn its citizens into “customers”, acted like Mohamed Sobhy in his play “Takhareef” (‘Superstitions’) when he asked about socialism. They told him that all the money would remain in the hands of the state, and he was content with the reply without hearing the second part of the sentence, which is that the state must spend on the citizens in return. As for me, even the status of a “free customer” does not apply to me, because I do not have the right to choose the merchant who I’d buy from, as there is only “one store”.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!