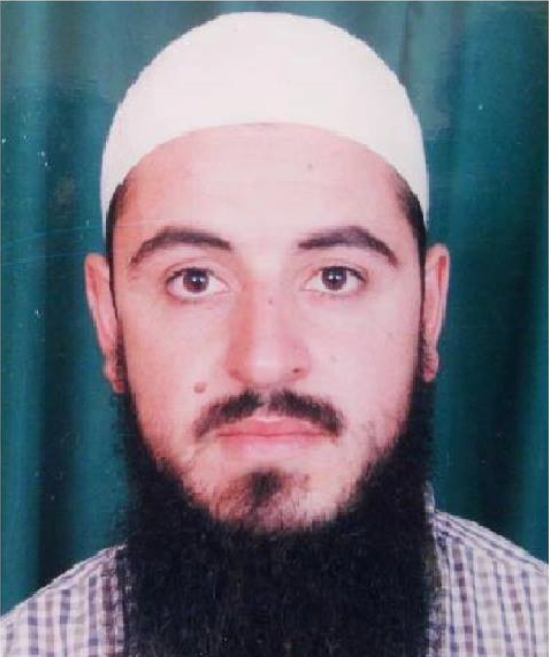

The life of former sheikh Khalaf Yousef before “The Black Ducks” had been very different from how it is now after “The Black Ducks”.

Here, “The Black Ducks” is not the title of a novel from classical literature or an iconic movie, it is an online talk show for Arab atheists that changed the man’s life.

These birds that spend their lives in swamps and marsh waters before they are slaughtered at the age of two months, can be compared to the life of Khalaf Yousef, with the only difference being that the latter was slaughtered by his community on the first day he announced his sexual identity and atheism.

The same man who rose to the pulpit (podium) as a young man and addressed worshipers at the age of twenty, was born twice: “The first time was the day he came out from his mother’s womb bearing the chromosomes of homosexuality,” in his own words, and the second was the day he willingly came out to make his homosexuality and atheism public in April 2013.

Many years of oppression and psychological torment stand between these two births - 38 years that saw Khalaf Yousef living in a borrowed body, “hiding in the closet” and chained down by his religious turban. During these years, his religious thought wavered between Hanbali Salafism, which dictates “murder or penance” at the core of its philosophy, and religious Sufism (Islamic mysticism) which calls upon the inward search for spirituality and divinity.

Pleasing others, an impossible goal

The respected sheikh, who led people in prayer in the mosques of Amman while being an atheist, admitted in an exclusive interview with Raseef22, “the biggest mistake of my life was when I listened to others and accepted an official position at the Dar Al Iftaa’ and when I gave in to my parents’ wishes to get married twice while I was very much aware of my homosexuality.”

Amman, Beirut, and Canada - a thread with three knots that depict the life of Khalaf Yousef, a man who knew that “pleasing people is an impossible goal to achieve”, and who focused on the science of men, biographies, and history.

Having spent 38 years in Jordan, amidst a society of tribalism, religiosity and lost identities. Twenty two months - almost two years - he spent in Beirut in the midst of a gay community burdened with its own problems. Six years in Canada, where he is currently based, and in a stable state of mind, in reconciliation with himself, with society, and his sexual identity, while also practicing his intellectual convictions. In January 2016, he had been able to find refuge in a deeply individualistic society that does not discriminate between people based on their sexual orientation.

The summation of these three lives, and his forty-seven years, is being currently documented in a book where he will dedicate a “rich” chapter to his Beirut era.

“In a country like Lebanon that suffers from rampant insecurity, I kept my place of residence secret, in case a religious fanatic or anti-homosexual decides to hurt me, especially since I'm accused of contempt of the Islamic religion”

Would Khalaf have started the Lebanese chapter of his life from the time he arrived in Beirut confused, thinking that he had taken the wrong flight and boarded a plane that landed at Tehran airport, after he saw photos of Iranian religious leaders littering the road to Beirut airport?

Or would he start from the first night he spent at a nightclub where he met members of the LGBTQ community near the end of Ramadan in 2014?

Or does he begin with his preparations to escape Jordan with the help of Jordanian human rights defenders and coordinating with the Lebanese Helem rights organization?

These can all be used as a suitable beginning for him to start telling his narrative of an era that he sees as the loudest and most active time of his life.

The “barbarity” of Beirut

Khalaf Yousef could not keep up with Beirut in all of its economic brutality, and its barbarity against a stranger who left his country for the very first time (other than for performing Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage), “I had to handle everything in my life on my own.

LGBTQ and human rights organizations did not help me. They could have found a home and a job for me at the very least. I did not even get legal support to prepare an application for asylum for the UNHCR.”

Perhaps the financial crisis at the time had prevented him from getting help and support, and this made him quickly lose any hope of counting on these organizations.

The first two months, when he lived in a room in the Ras Beirut area, were marked by torment, anxiety, loss and a sense of “culture shock”, after he quickly discovered that the beautiful Lebanon that he had hidden beautiful images of in the back of his mind, is not actually so rosy.

On his first night out, for instance, he heard plenty of sweet talk from some of the LGBTQ people there, but later discovered that it was merely the kind of talk that - mixed with a night full of dancing, teasing banter and the daze of alcohol - cannot be relied upon.

Beirut, with its rare moments of sweetness and abundance in bitterness, refuses to leave the memory of Khalaf Yousef,

“How can I forget it when it threw me out in the open for three nights, in late October 2014, when I only had a small amount of money?”

The sheikh who led prayer in Amman's mosques while being atheist admitted: “My life's mistake was when I accepted an official Dar Al Iftaa position and gave in to my parent’s wishes to marry twice while aware of my homosexuality”

Besides phone numbers with basically zero practical value, and people who suddenly disappeared from around him, he collected his few remaining dollars, gathered his things, and let his feet lead him out into the unknown. After some time, he went to a mosque asking for an overnight stay, but the sheikh there turned him away.

By day he would walk up and down Hamra Street, and at night, when he grew weary and the city fell asleep, he went to the rocks across from the famous Raouché rock and succumbed to a fitful sleep.

On the third night, he tried his luck with a church. He jumped over its wall, but was surprised to find the church minister standing tall before him, “I hastened to calm the clergyman. I assured him that I am not a thief, and then I listed the reasons for my escape from Jordan.”

But, because he was afraid that the cleric would throw him out, Khalaf skipped over the particulars of his homosexuality, very much aware of the Church’s severe stance and refusal when it comes to the issues of sexual orientation.

Surprisingly enough, things went quite smoothly. The clergyman checked his passport and then took him to a room downstairs, “He supplied me with a mattress, ordered some hot food from a restaurant for me, gave me two hundred dollars, and allowed me to stay until I found a place to live.”

Into the unknown

The southern suburbs of Beirut, Dahieh, specifically the al-Laylaki area, became Khalaf Yousef’s semi-secret home address for a year and a half. A Lebanese girl from a Bekaa clan found him a room inside a building that provides university housing, and on the day he moved in, he kept seeing more and more party flags and photos, but he paid them no heed.

A friend later told him that by moving to Dahieh, it was as if he was throwing himself into the jaws of the unknown, especially in such an unfamiliar area with active drug dealers.

He asked him: What if this socially and religiously conservative environment discovered his sexual orientation and atheistic views? What if security alerted the forces on the ground to the presence of a Jordanian living in their midst, along with all the accompanying security doubts that would arise around him?

These were all questions that Khalaf did not have the luxury or time to find the answers for. His main concern was to find a roof over his head, four walls to stand around him, and a soft pillow.

Unfortunate happenstance saw him sharing his dormitory in the al-Malak Building in the al-Laylaki neighborhood with a young man named Shadi (false name). Two weeks after the roommate dragged him into a minor dispute, his body was found under a bridge in the Sin el Fil area of Beirut.

Khalaf became a part of the ensuing investigation, and was interrogated for six hours in three intervals that raised his adrenaline levels, especially since he was afraid of where the investigation would lead and the possibility of them looking into his identity or asking the Jordanian authorities for information about him.

Naturally, he avoided mentioning any details about his sexual identity for fear that he may open doors he doesn’t know where they’d lead, especially since he was well aware of the fact that Lebanese law criminalizes homosexuality, and the abuses that security services commit against members of the LGBTQ community, and especially following the Hammam al-Agha Turkish bathhouse raid.

Fortunately for Khalaf, the investigation was conducted before he began posting videos about his atheism and sexual orientation on his social media pages. So what is the story of the videos that began to break the taboo in March 2015?

An anonymous Facebook account with a blank wall photo and no content contacted Khalaf on Messenger. The private message, which turned out to be from a gay Qatari named Ahmad, told Khalaf that he had seen his “The Black Ducks” video and felt that he was speaking in his stead and that their two stories were the same.

Not long after, the previously religious Qatari man turned into an atheist, “thanks to me,” Sheikh Khalaf said with a laugh. He continued, “Ahmad became an atheist. He was influenced by my ideas after we discussed them for hours on Skype and Messenger.”

After the Qatari noticed that Yousef had previously requested financial assistance from his friends, he took it upon himself to transfer a monthly amount of money to cover his costs of housing and daily expenses.

The smart phone he had bought with this generous financial assistance led him to begin working on his social media activity.

From his room on the 9th floor of the al-Malak Building, he began recording videos that talk about homosexuality in general, gender issues, and criticism of Islamic heritage.

His followers increased, but fortunately none of those he lived among recognized him.

In one of his videos, he responded to a threat he had gotten from a religious account that calls people to “True Religion” and is run by a Syrian citizen from Homs. The threatening video spread like wildfire and circulated photos of Khalaf calling for his death. Fearing the threat, he would rarely go out and, if he had to, it would be in disguise. He says, “In a country like Lebanon that suffers from rampant insecurity and lawlessness, I made sure to keep my place of residence a secret, in case a religious fanatic or anti-homosexual decided to hurt or kill me, especially since I am accused of contempt and distorting the Islamic religion because of my sexual orientation”.

The most vexing threats came from his own relatives. Two of his brothers went to Beirut to look for him, “The UNHCR suggested that I change my residence and reduce my activity on social media. They also provided me with a hotline number to report any threats.”

Aside from a passing sarcastic comment in an internet café about the increase of what they called “homosexuals and queers” in the area that did not generate any reaction, one year and six months living in the suburbs did not arouse any suspicion or raise doubts about him.

When demonstrations against the regime’s corruption and the drowning of Beirut in garbage began in 2015, Khalaf Yousef took to the streets to chant along with the people of Lebanon: “The people demand the fall of the regime”. He took part in the protests with members of the Helem organization on three separate occasions, raising the rainbow flag and calling for the abolition of Article 534 of the Penal Code that criminalizes homosexuality based on “sexual intercourse against nature”. They also demanded the enactment of modern laws that protect the LGBTQ community and observe their developing concepts in both the Lebanese and international societies.

The people he led in worship used to weep when they’d hear his voice reciting the Quran. Today, his story brings tears to the eyes of his Western audience as he recounts episodes from his plagued life

Among his stops in Beirut was a bold and unique lecture that he gave on homosexuality from the perspective of the Islamic religion, “Between 10 and 15 people were expected to attend, but more than 150 people gathered for the event, and included religious clerics. It was scheduled to last half an hour but lasted for four hours and made a huge impact.”

Beirut’s doors remain open to Khalaf as a tourist or a resident, but he assures that he will not take such a step, “I cannot live out my homosexuality there. A large segment is still hostile towards homosexuals, Lebanese law cotinues to criminalize their practices, and religion is unfair and intolerant.” And given that Jordan’s doors are closed in his face because he is accused of contempt of the Islamic religion, Canada still has its arms open for him, where he can spend his life in comfort and safety in the western province of British Columbia.

Thus, after Khalaf Yousef used to stand on mosque podiums, he now stands on podiums to present his stand-up comedy shows, where he would briefly talk about his homosexual life in the Shakespearean language.

The people he led in worship used to weep when they’d hear his voice as he recited supplication (Du'aa Qunoot) to the sad melodies of youth. Today, his story brings tears to the eyes of his Western audience as he retells the ups and downs that plagued his life.

This project is in cooperation with the Arab Foundation for Freedoms and Equality (AFE) and with the support of the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

This article is part of the “Raseef in Color” project, a space dedicated to male and female activists as well as members of the LGBTQ community and their supporters, to be able to speak freely and without any restrictions about different gender and sexual orientations, and sexual health. The project is also aimed at contributing to and spreading scientific and cultural awareness of gender issues, through innovative and comprehensive approaches simultaneously.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!