I fell in love with a Christian young man, I, the daughter of a Muslim family from South Lebanon. Things seemed easy and we did not face any difficulties in convincing our parents of our relationship, since my family is not religious, and some of my relatives had already experimented with civil marriage in Cyprus.

My husband’s family is religious, but it accepted me and the decision of their son. Even though he is the only one in the family who married outside his sect, they didn’t object to our wish to have a civil marriage.

But there was a sudden plethora of disturbing reactions that came from our wider social circle, which allows itself to comment on and question the future of our children, their upbringing, and how to deal with cultural differences. An ‘observing’ Muslim friend even told me that children that come from a non-religious marriage are bastards. This was the worst comment I had heard yet.

Months passed since we got married and I still sometimes hear strange comments, like someone saying that they didn’t feel like I got married, because any marriage that’s not subject to the conditions of social and religious authority is not a marriage recognized by the sect.

Today, my husband and I live in the United States. Despite this, the most frequent question that I have to answer when I meet Lebanese people is: “Where are you from?” The purpose of this question is to determine my religious affiliation depending on the region that I come from in Lebanon.

- I answer: From the South.

- The South? You mean Jezzine? (a region inhabited by a Christian majority)

- No, from the Nabatieh. (inhabited by the Shiite sect).

I notice how some become confused, and do not understand how my husband is Christian and how I come from an area where there are no Christians. Most of these people are from a Christian background and left Lebanon following the civil war or before it had ended. In exile, they did not socialize with others except with those of their own environment.

After I got married, I started to hear stories of people who are suffering just because they love someone outside their sect. My Christian friend announced to his parents that he loves a Muslim girl, and although they accepted it, his sister who loves a Muslim man feels like it would be impossible for her to tell them of her relationship.

The Economic Collapse Complicates Things Further

Before she fell in love with Dominic, Roa’a never thought she would experience fear when the time came for her to tell her family she was in love. She tells Raseef22 that the reason for her fear comes from female relatives of hers who had loved young men from outside the sect before her, but pressure from the family prevented them from continuing their relationship. So she kept her relationship a secret because she thought the family would stand in her way.

Roa’a is from the Shiite village of Adloun. She studied French literature, and met Dominic while taking Civil Service Council courses to become professors in formal education. Dominic would visit her in her southern Lebanese town so that they could study together and they began to have feelings for each other that turned into a relationship. Roa’a didn’t dare tell anyone because they each belong to two different religions. She only told her brother that she was in a relationship with a Catholic Christian man, since he doesn’t think the same way the rest of her family does. In return, she hid it from her sister despite their close relationship, fearing her reaction.

Roa’a recounts what she went through before she was able to reveal the fact that she loves a Christian man, “This issue took a great deal of psychological effort out of me, and I would not have done it (revealed my relationship) if it wasn’t for the increasing obstacles standing in the way of our ability to meet.” She states, “We are from two different communities, and I wasn’t able to enjoy the complete freedom to meet him because I am a young woman from a somewhat conservative environment, so I decided to tell my parents that I wanted to marry Dominic.”

The young woman’s family asked her to slow down and take her time with this, so that they could consult with extended family members and seek their opinion on such a matter. Fortunately, the family agreed, but “on the one condition that Dominic becomes Shiite and that their marriage is officiated before a Shia Muslim cleric.”

As for Dominic, he “did not face any issues, and his family visited my family, expressing their happiness over this.” Roa’a believes they have a common denominator that helps overcome their religious differences, which is that they are both “village residents and have common social backgrounds, even if we are from two different religions.”

Since adolescence, Roa’a has wanted to have a civil marriage so that she could avoid the injustices that women face in religious courts, especially when it comes to their rights and the custody of children. She has a friend who has “been through hell and back and was deprived of her children, and today she is still fighting to see her children.”

The young woman would always tell her mother that “even if I marry someone of the same sect and my marriage is officiated by a religious cleric, I will also get a civil marriage and register it in order to protect my full rights as a woman, since personal status laws in Lebanon are unfair to women.”

However, under Lebanese laws, even if a civil marriage takes place abroad between two Muslim partners, it is the religious courts that settle the dispute between them - a fact she hadn’t known about.

In Lebanon, each sect manages its own matters of personal status, i.e. the affairs of marriage, divorce, custody and inheritance. Each sect has its own religious courts, whose cases are decided by clerics who do not necessarily always have a solid legal academic background.

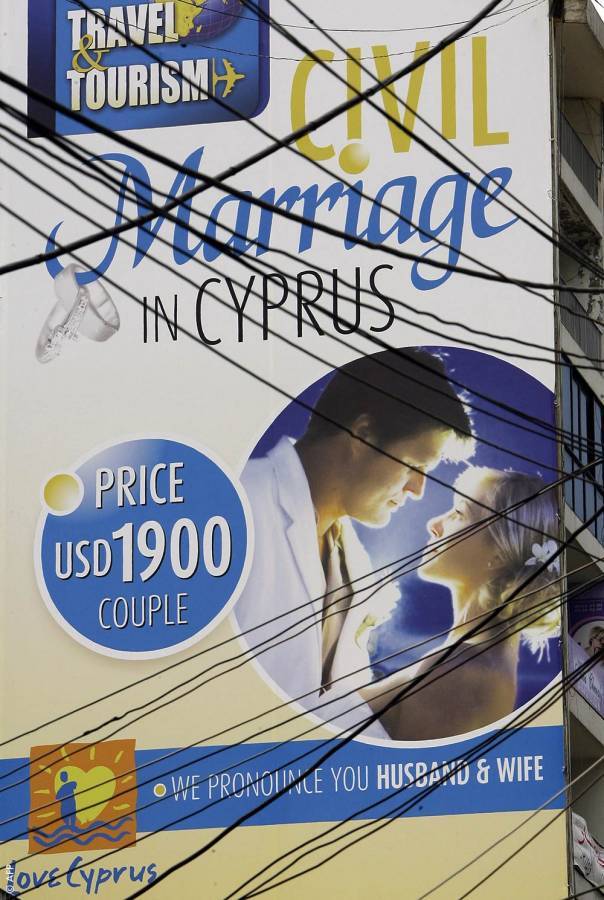

The absence of a unified civil law for personal status poses a difficult dilemma for those who wish to marry outside their sects. Most Lebanese people resort to resolving this dilemma by traveling abroad, often to Cyprus or Turkey, to get a civil marriage. The Lebanese state recognizes and agrees to register civil marriages that have been contracted outside Lebanon, but there is no law that allows civil marriages to take place within the country.

Those who plan on having a civil marriage outside Lebanon face costs of no less than 1,500 US dollars for travel and hotel reservations, in addition to legal paperwork fees. This cost limits the ability and desire of people with low incomes to free themselves from the authority of religious courts over their personal status. It is even worse when the two partners are of different faiths. Their inability to afford the costs of travel becomes yet another obstacle to getting married. In this case, the couple has no choice but to pay a different kind of price by taking steps like Dominic and Roa’a did.

When Roaa’s family asked Dominic to become Shiite, “we didn't mind,” Roa’a says. The couple saw the whole thing as a front, especially since Roa’a has previously crossed-out her sect in the official status register (locally known as ‘Noufous’), and therefore she herself does not belong to the Shiite sect in terms of official paperwork.

The couple were planning on having a civil marriage abroad, provided that “this would be the official marriage between us,” says Roa’a. However, the economic collapse, the devaluation of the Lebanese pound versus the US dollar, the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of airports prevented “our ability to travel and afford the expenses.” That is how they ended up registering a religious marriage against their wishes, and how Dominic “officially became a Shiite on paper”, that is, in the state’s records.

The Power of Religious Authority over Collective Identity

The Director of Legal Agenda, Lama Karame, says that the process of seeking to adopt civil marriage in Lebanon began in the 1950s, and more than one draft law was submitted to legalize civil marriage in Lebanon, some of which were optional while others were mandatory laws, but none of them was approved.

She tells Raseef22 that “the first official registration of a civil marriage contracted on Lebanese soil took place in 2013, when Kholoud Sukkarieh and Nidal Darwish got married. This civil union was registered based on a circular issued by former Minister Ziad Baroud in 2009, in which he gave the option of removing any reference to religious affiliation from civil registry records.”

In our patriarchal society everyone is subject to the authority of the patriarch (father, brother, religious leader). A man marrying outside his sect doesn’t threaten the community as much as a woman marrying outside her sect

Karame explains that “the Sukkarieh-Darwish couple based their move on the French Mandate Decree 60 L.R. issued in 1936, which stipulates that people who are not subject to any of the historical sects (meaning the sects recognized in Lebanon) are subject to civil laws.”

She notes that despite the registration of some marriage contracts according to the text of the law, “successive interior ministers have refused to register the civil marriages, and there are many marriages that were suspended, forcing some people to resort to getting married outside Lebanon or just have a religious marriage.”

The demands for civil marriage intensified with the appointment of Raya El Hassan as Minister of Interior in 2019, after she announced that she wanted to open the door for discussion with all those concerned, but various religious authorities announced their complete rejection of such a step.

Before her, former Interior Minister Marwan Charbel had agreed to register the first civil contract (between Kholoud and Nidal) before a notary on Lebanese soil in 2012. Also during the days of Minister Charbel, the last civil marriage contract on Lebanese soil was registered. The civil union, held between Fatima Hashem and Jean Nmeir, became the last one in the country after his successor, Minister Nohad el-Machnouk, refused to register any civil marriages made on Lebanese territory.

El-Machnouk became known for a phrase he said in response on a television talk show: “Cyprus isn’t far,” indicating that whoever wishes to break sectarian barriers and open the door to intermixing between people of different sects and their families, must pay a high cost, with travel expenses only being a small part of it.

Despite the Interior Ministry’s refusal to register civil marriages in the country, Marie-Joe Abi-Nassif and Abdallah Salam had their marriage done before the notary public in Lebanon this year. Karame says that in this regard, this marriage “has not been officially registered to date.”

Karame says that “when two people have a civil marriage in Lebanon, personal status courts decide on marriage disputes, i.e. divorce, inheritance, and custody. And the civil court is just a civil chamber within ordinary justice courts.”

With regard to civil marriages between Lebanese people abroad, she clarifies that “civil courts are also the ones that decide on disputes, with the exception of marriage between a Muslim man and a Muslim woman, where Sharia courts have the power to decide on disputes. As for the Druze, a law was issued by the Court of Cassation (or Supreme Court), which recognizes that the civil courts are competent to settle disputes between litigants as long as they have a civil marriage.”

Hala Awada, researcher and assistant professor at the Institute of Social Sciences at the Lebanese University, attributes the rejection of mixed marriages in Lebanon to the role played by the “critical history of sects and demographic conflicts”.

She tells Raseef22 that despite the significant role that religious sects play in hindering mixed marriages, in contrast, “a very important factor that cannot be overlooked is how clerics of all religious sects fear losing their role in the process of marriage, it threatens their position both morally and financially.”

Dr. Awada’s words remind me of a story that my friend told me as she was trying to understand how I was able to “convince my family” of my marriage. She told me that she has been trying to persuade her Christian family for five years to marry her Muslim partner, and all she hears in response are phrases like “They killed us in the war. You want to marry them?”, “One day he will get a second wife,” and “We cannot go to their regions”.

They also remind me of the story of a Christian young man who married a Druze woman and had to emigrate from Lebanon so that he and his wife would be safe from any attempts of murder. Twenty years have passed and the couple still lives abroad to this day.

In Lebanon, slogans of tolerance and coexistence fall during the first test, namely marriage outside the sect. It falls apart because it becomes a threat to the set of principles that the group has drawn for itself

Awada relates the issue of the obstacles, fears, and difficulties people face because of mixed marriages, to the “social identity of the individual.” She explains that “the difference between human beings sociologically comes from a social need for them to join a group that works on defining its goals and principles, as well as the roles and positions of those who belong to it through certain classifications of the individual’s identity, and that is how the collective identity of an individual is formed.”

Awada bases her words on Henri Tajfel, the founder of the social identity theory, to explain how a group, from the beginning of its formation, “seeks to distinguish itself through ‘us and them’, and this applies to all forms of grouping and does not stop at religious groups only.”

But it so happens that the individual identity sometimes collides with social identity, and on this, she says that “when the social identity of the individual is formed, his affiliation to the group becomes a central matter with strong emotional bonds binding him with it. As an individual, he adopts strategies in order to distinguish his group from other groups in a positive manner. However, at certain moments, the individual’s personal identity clashes with the values of his first group, to such an extent that it no longer meets his personal ambitions that stem from his individual identity. That is when he begins to adopt a strategy of individual movement in order to improve his image of himself, so he leaves the first group and joins another group in pursuit of individual goals. Here we may understand how an individual leaves his group, marries into another sect and affiliates himself with it, or how he rejects all existing groups, has a civil marriage, and forms a new group that does not adopt the values and standards of his first group nor that of his partner’s. So we are in the process of forming another group with its own new standards and values.”

As for the specificity of groups rejecting mixed marriages, Awada says that “marriage and thus childbearing, which is more important, is a vital issue meant to reproduce the ‘us’ as opposed to the ‘them’ for a group.” This is how in Lebanon, “slogans of tolerance and coexistence fall during the first test, namely marriage outside a cultural religious sect, and the slogan falls apart because it becomes a threat to the set of principles, ideas, and behaviors that the group has drawn for itself and works to raise its children on.”

According to Awada, this threat arises when “a guest that isn’t affiliated with a sect comes to this group carrying a set of different ideas, principles, and behaviors that constitute a threat to the unity of the group.”

“Do Not Marry a Muslim”

Samer and Rita (pseudonyms) got to know each other through engaging in political activism, having similar left-wing and non-religious orientations. Rita comes from a Catholic Christian family, while Samer is from a Sunni Muslim family, but neither of them follow the beliefs of their families, or any other religious beliefs. Their relationship went on for five years, after which they decided to get married in Lebanon in 2010.

Unlike Roa’a, neither of them was afraid of informing their families of their desire for marriage, but what was surprising was “the amount of questions we were asked about how we are going to raise our children,” Samer tells Raseef22,“I think it is difficult for some people to understand what it means to be an atheist and irreligious.”

Samer and Rita decided to start the procedures for a civil marriage, regardless of their families’ position, but the fact that Samer had no nationality prevented him from getting a visa to travel to Cyprus. Since the couple had previously set the wedding date, they had to think of a solution besides postponing. They went to a Catholic church to have Samer convert to Christianity and then get married in the church, but the authority of the clergyman to accept or reject a person into his sect exceeded the couple’s expectations.

In the church, after being asked why he wanted to “become a Christian”, Samer admitted to the minister that he was doing so “for the purpose of getting married”. Then the minister turned to Rita to ask her a question full of reprimand: “Why do you want to marry a Muslim man? Have you thought about the future of your children later?”

- Rita: We love each other and have been in a relationship for five years.

- Samer: I am ready to sign a pledge that I will baptize our children in the future if it’s a condition for our marriage.

But the minister rejected their love, and denied Samer the religion of Christianity.

- Rita: What should I do now, should I go get married by a Muslim cleric and become Muslim?

- Minister: No, do not marry him at all, you must only marry a Christian man.

The couple then went to the Maronite Church, which agreed to allow the young man to join its parish. But when it found out that Rita was Catholic, the minister there informed them that he could not wed them in his church.

The originally irreligious couple had no choice but to attempt to consummate their marriage before the Sunni Sharia court, after they discovered that a Muslim man may marry a Christian woman without her being required to change her religion, provided that the children are brought up by the teachings of the Islamic religion.

Love stories between people of different sects aren't like ordinary love stories, not because they're between people marginalized by law and rejected by sectarian society, but because these relationships face constant attempts to abort them

Samer says, “If it was possible for us to have a civil mariage, we wouldn’t have had to resort to clerics wanting to dictate their terms and conditions on us.” He adds that even when they were registering the marriage at the Civil Registry Records, “there was an intentional delay by the registry officer, to the extent that we had to use an intermediary to complete an ordinary marriage registration.”

The two lovers had their first child, and their small “mixed” family added a new member. “When I became a mother, I began to feel afraid for the fate of my children and my right to guardianship and custody in case of any dispute between me and Samer,” says Rita.

For his part, Samer expresses his fears “in case something happens to me or I die”. He is specifically afraid of his family taking custody of his son because his wife is still Christian, and he is also afraid of the issue of dividing the inheritance.

Samer says, “We are experiencing all of this, even though we are non-religious people and do not care about these matters. We just wanted to get a civil marriage and raise our children the way we want.”

Currently, the couple lives in a foreign country where they have obtained citizenship, and it’s governed by civil laws.

A Man Cannot be Shamed or Disgraced

Lara (pseudonym) never thought that she would meet the love of her life in the new building she had moved to live in within one of the neighborhoods of Beirut. Her partner Elie comes from a Christian family, while she comes from a Druze family.

Lara describes her family as “secular, and not religious or extremist”. Despite this, “When I told them that I was in a relationship with a Christian young man and wanted to marry him, they were surprised, as my father never expected that I’d marry someone outside the Druze sect.”

She adds to Raseef22, “My father’s fear was of their surroundings and environment they live in, the reaction of the Druze community, and what people would say. It was not based on religious conviction or attachment. It was first and foremost a social fear.” On the other hand, “Things were much easier on my husband’s side. This is because we live in a patriarchal society, not just a sectarian one. A young man cannot be shamed or disgraced by anything, while the girl always pays the price.”

In this context, Dr. Awada says that “our society is patriarchal where both women and men are subject to the authority of the patriarch (father, brother, religious leader of the sect), and therefore the marriage of a man to a woman from another sect does not threaten the community as a woman marrying outside her sect does. That is why it is not easy for a woman to marry someone outside her religion, because she is not completely free from the control of the greater patriarch.”

She indicates in detail that “the most important issue here is inheritance, preventing property dispersal, and strictly keeping the issue of inheritance up to the man. Secondly, because she is a woman in a patriarchal society, she will be subject to the rules and criteria of the group she joined, even if just on the surface, whereas this does not apply to males.”

Awada continues, “It is known that minorities fear the fragmentation of their ownership (right of possession), and families fear the fragmentation of their lands, so they prefer to have their male sons marry into the sect or even into the family itself, much less when it comes to their female daughters!”

Lara did not hear any direct comments about her decision to marry Elie. Any objections to her actions were directed towards her family, and she knows that some of her parents’ friends repeatedly tried hard to tell them that such a thing is unacceptable and is contrary to their customs and traditions. But Lara overcame these difficulties “through long talks and conversations with my family, and we finally reached an agreement where they acquiesced to meet my partner, and then would make their decision after that.”

After the parents got to know Elie, “they were convinced that I was right and that my decision was not only made out of love, but also out of maturity, understanding and mutual agreement.” On the other hand, many members of the extended family, “like my grandmother, have still not accepted this marriage to this day,” says Lara.

Lara believes that the more there are mixed marriages in Lebanon, the more the “sectarian boogeyman” barrier will be broken, because getting closer to the other breaks down many barriers and reveals that most of the preconceived ideas regarding other sects are incorrect.

She says, “Closeness makes us more aware of the social backgrounds of people. There are many points in common between the sects in Lebanon, even more than the points of difference, and this is what I noticed after my marriage, as my family and Elie’s family acted as if they were one family with no differences between them.”

Like any person in Lebanon who chooses to “intermix”, Lara and Elie are subjected to “cliché” questions like, “What holidays do you celebrate?”

For Lara, intermixing is a “rich source for us and is an occasion to celebrate more with the family.” She adds, “It makes me happy that my children can learn about two different religions and have enough awareness to know that religion is a vertical relationship between the individual and his God and not a horizontal relationship between the individual and society along with its prejudices.”

Before the Ministry Changes its Mind

Fatima Hashem married Jean Nmeir in 2013 on Lebanese soil. The two architects living in Lebanon decided to fight the battle for freedoms and liberties by crossing off any religious affiliation from their civil registry records and having a civil marriage in Lebanon. This was the last civil marriage recognized by the Lebanese state, before El-Machnouk’s infamous: “Cyprus isn’t far.”

Fatima and Jean went to the mukhtar (official in charge of civil paperwork in a region), who gave them a paper stating that they wanted to cross out religion from their civil registry, then they went to the Civil Registry Records to implement this procedure. Fatima tells Raseef22 that due to the absence of a civil law in Lebanon, they based it on the French mandate law, which requires that they announce their marriage beforehand by ‘suspending it in the home or workplace for 15 days’. After completing these formalities, they tied the knot at the notary public.

Neither Fatima’s nor Jean’s family accepted that they married a person outside their sect, but they carried on fighting this battle to the very end. Fatima says that her mother “used to pray and ask God what she had done wrong that her daughter decided to marry a Christian, and Jean’s mother also used to go to church seeking forgiveness.”

Love stories between people from different sects are not like ordinary love stories, not because they are stories between people who are marginalized by the law and rejected by sectarian society, but because these relationships face an uphill battle as well as attempts aimed at crippling them through all possible means, to such an extent that a person feels like he is in a constant state of war just to realize his individual choice.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!