Spaces in Beirut reflect their visitors. They reveal their tastes, desires, and even their financial means. Many stores closed their doors, their owners struggling to preserve what’s left in their pockets, and others adopted a new lifestyle in line with the aftermath of the collapse.

Some have had to say goodbye to their favorite corners destroyed by the explosion, and others simply can no longer afford them. In light of the fast-moving events that keep catching the Lebanese, the face of the city began to change, leaving only its seafront open to all.

The young men sit on the rocks by their coals and hookahs. Ahmed refuses to play with his siblings because he has no desire to do so. A little girl counts the waves and she and her friends are caught off guard by the rat that scurries away

On the seaside promenade (corniche) that runs along the entire city, all social groups and classes come together. Here, according to Hassan, there is no cost of entry and “we are all equal under the same sky”. In Beirut, a city suffocating under concrete and projects outlined by cafes, restaurants, bars and malls, residents have nothing but the seafront as their last outdoor haven, and even today, they continue to crowd its pathways despite the darkness it’s been plunged into.

The Oldest Flower Seller by the Sea

Caption: Firas al-Abdallah - Photo by Jana Khoury

Caption: Firas al-Abdallah - Photo by Jana Khoury

Firas al-Abdallah tips the flower vase on his left shoulder and then repositions it on his right shoulder as he offers his roses to the passersby who smile at him, describing himself as the oldest flower seller on the shore line.

37 years ago, when he was only four years old, Firas left his displaced parents’ house in Wadi Abu Jamil and headed to the Corniche to pull himself out of poverty by selling roses. From this profession, he was able to support his parents and then later have a family of his own. Firas recalls the days of the “chairs and umbrellas” and the days of war. He asserts that the military war was actually easier to deal with than the current economic war, and that the corniche has changed a lot. He says, “Everyone knows who Firas is, and that he is the oldest flower seller here. The corniche was and still is an outlet and haven for the poor, so I do not put a price on my roses. I just let the person set the price so as not to embarrass him in front of his girlfriend. When I see people smiling like they used to before the economic collapse, I give them my rose for free.”

He adds, “Decades ago and before the collapse, people used to fill the corniche and smile despite hardships. Today we do not see faces because of the absence of light, but we know that everyone is deeply fatigued, and it is changing the features of the corniche.”

Caption: A street vendor in the Manara area - Photo by Jana Khoury

Firas’s words aren’t only metaphorical, for faces can only be visible from a very close distance there, because darkness has taken over the sea front. The buildings across the street and cars passing by can only reflect so much light. In order to walk without tripping or bumping into pedestrians or bikes, we must use our phone lights. From a distance and in the midst of the darkness, the sound of music blares. We follow it and reach Yasser al-Sheikh Musa.

Music for the Entertainment of Passersby

Caption: Yasser al-Sheikh Musa - Photo by Jana Khoury

Caption: Yasser al-Sheikh Musa - Photo by Jana Khoury

Yasser sits on a wooden bench, surfing through the playlist on his mobile phone. He is undecided, but then he chooses a song that everyone near him will hear. He greets us and shows us how his phone couples with the speaker. A small personal joy of his that he invented just like his ritual of coming to the Manara to sit with his friend and broadcast songs out loud.

I put on music that I like and take pride when people see me accepting their requests. Everyone enjoys it, and no one objects, except for the state. The state objects, and its men come towards me, saying, “Turn it off.”

Today, Yasser is alone because his friend is at odds with him for a reason he does not know. He explains that he comes here because the electricity is almost always cut at his house in the Basta Al Tahta area, and he cannot afford the costs of a private generator service (ishtirak), which is why he goes out to have fun in his own way, despite the encompassing darkness here as well. He says, “Here there is sea and air, in the house there is only walls. Here I also put on music that I like and I take pride in myself when people see me accepting their requests and when I create an artistic atmosphere that attracts passersby. Everyone enjoys it, and no one objects, except for the state. The state objects, and its men come towards me, saying, “Turn it off please.” So I move from the bench to my motorbike parked behind me and carry on with my evening broadcasting music from on top of my private property.”

We Used to Hear the Sound of Laughter

Caption: Hassan Kotaish - Photo by Jana Khoury

Street vendors flee the municipal police. They run toward the highway, uncaring of the speeding cars and fearing that they will rob them of their livelihoods. According to Hassan Kotaish, 28, selling coffee is prohibited and there is no legal way out to save him from the current situation.

In light of the fast-moving events that keep catching us unaware, the face of Beirut began to change, leaving only its seafront Corniche open to all

Hassan believes that security forces are making things more difficult for people and vendors. He says, “The hookah is prohibited and selling is prohibited. It is as if the state is forcing us to sell our organs in order to go to cafes just to have a cup of coffee. I do not know what their plan is and whether they want to turn the only vital public lifeline in Beirut into private property.”

Hassan, a street coffee vendor, is looking for legal solutions that would allow him to work in a public place, and stresses that the state does not want to offer solutions. He has been making a living from this occupation for three years now, fleeing from the security forces in fear that they would take his work tools from him. He states “There is no clear legal article that prevents a citizen of the country from working as a street vendor. There are groups that want to decide the way the country operates, and this is a concoction that they invented. They demand of us to get a licence, but if I go to the municipality or governorate, I will find out that there is no way to get a licence.”

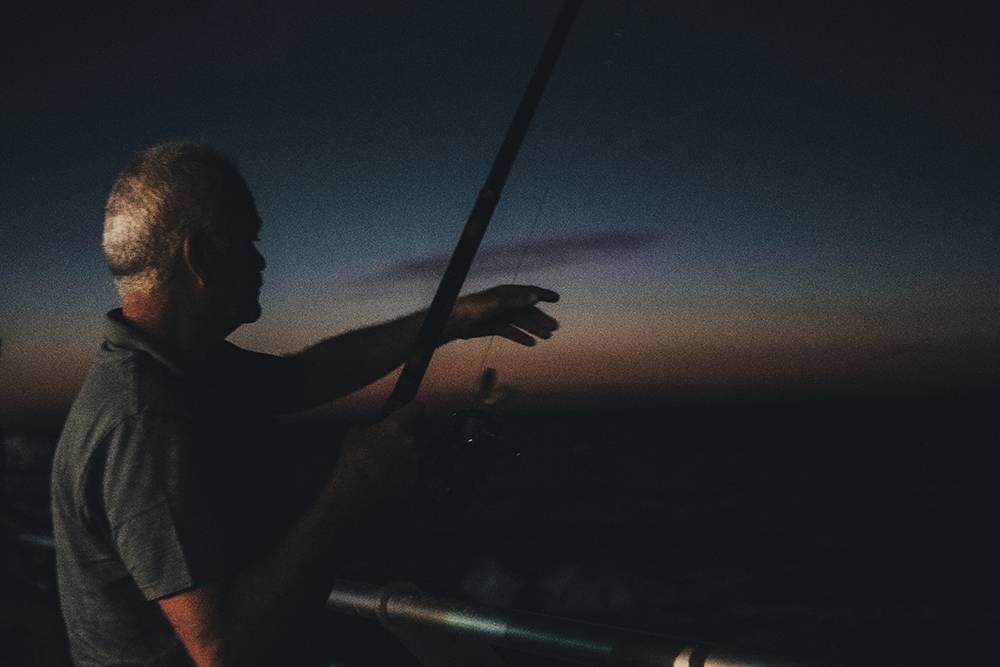

Caption: A fisherman in the Ain al-Mraiseh area - Photo by Jana Khoury

Between the cheese man’ousheh and the za’atar (thyme) man’ousheh, Hassan buys the latter in order to save four thousand Lebanese pounds. He goes to the corniche to work and support his disabled father. He insists that young people are out of work, instead of unemployed, and that they only have this free spot that they go to despite the drastic changes that have taken place. He explains, “Three years ago, we used to hear the sound of laughter and see families gathered together. Today, people are weary, anxious, and sulking, sitting without a trace of light. Despite this, they all come here to escape their homes - homes without electricity and food - to wander Beirut, where the state will soon put a meter on our mouths so that we would pay for every breath we take.”

An Amusement Park for Children... and a Haven for Adults

Caption: Lamya al-Amin and Amal Kobeisy - Photo by Jana Khoury

Mohamed Ibrahim brings his three-year-old son to the corniche because he cannot play in their dark house or in the public park near his house in the Bourj Hammoud area, after it was closed down at the start of the COVID pandemic. His wife, Raghida Ibrahim, asserts that the children do not understand that there is a crisis. They only understand playing. She says that in the past she used to take her son Ibrahim to the amusement park, but today she is unable to pay the ticket price. Thus the corniche has turned into a new amusement park with borders that stand between the public road and the sea where he plays and she and her husband and mother-in-law sit on the benches.

They turn their backs to Beirut and turn their faces toward the sea, taking a few breaths under the sky in a place that is considered the last public space in the city

In contrast, Amal Kobeissi, a retired French language teacher, chose to return with her friend Lamya al-Amin to the corniche following a year-long absence. She explains that she left her home in the Tayouneh area, and chose the corniche because she had been unable to head to the Mount Lebanon region that night with her friend. She wanted to breathe, enjoy nature and avoid closed spaces amid fears of the Coronavirus.

Upon returning a year later, Lamya explains that she was shocked by the overwhelming darkness covering everything, but at the same time she found out that people still go to the sea front in order to relax and breathe in the only, final place with this much nature in Beirut.

Caption: Ain el Mreisseh Corniche - Photo by Jana Khoury

From Ramlet al-Bayda all the way to Ain el-Mreisseh, people do not see each other. We hear children playing and running and catch a glimpse of the ball as it passes by. Cafés and restaurants are not available to the majority of the people, and citizens are trying to fight off this crippling unemployment by selling coffee and corn cobs along the corniche. The young men sit on the rocks by their coals and hookahs. Ahmed refuses to play with his siblings because he has no desire to do so. The little girl counts the waves and she and her friends are caught off guard by the rat that scurries away between the rocks. Some run, some sit, and some dance. Everyone turns their backs to the city and turn their faces toward the sea, taking a few breaths under the sky in a place that is considered the last public space in Beirut.

Caption: Ahmad - Photo by Jana Khoury

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!