“I applied to every single refugee service — from aid, to education grants for children, even blankets (winter aid), and the Carrefour card (food supplies aid) — but the outcome was rejection after rejection because I am a ‘Palestinian refugee’. Even in light of the Corona pandemic and the increasing of aid for refugees in need, my family and I were not given any support.”

This is what Shaker Abdah told Raseef22 about the dealings of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Egypt and how they have been handling matters with him ever since he and his family arrived in Egypt more than 15 years ago. They had fled from Gaza due to compelling humanitarian circumstances that the head of the family informed us of but preferred not disclose.

Shaker was pleased with the swift acceptance of his application for his family’s asylum upon contacting the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner in Egypt, thinking that the resettlement and stability of his family in a safe country was finally at hand. However, he claims that he went on to spend many years knocking on the doors of the commission and waiting in its queues without knowing what fate had in store for him and his family and without acquiring any service or assistance.

Shaker is not the only one complaining about the “ill-treatment” at UNHCR in Egypt, for five other refugees made plenty of allegations to Raseef22 about violations they had suffered from or witnessed inside the UNHCR or within two institutions — one relief and the other legal — cooperating with it. Also, the majority of the comments on the Facebook posts of the official UNHCR account are negative and dominated by a tone of disapproval and denial, attacking the organization’s “lack of commitment” to its tasks or pledges, as we have observed.

How Does the UNHCR Work?

Raseef22 reached out to UNHCR’s spokesperson in Egypt, Radwa Sharaf to take on the issue. Sharaf explained the way the organization operates, declining to comment on “singular instances and problems that some refugees encounter”. She adds that the UNHCR “does not possess sufficient information about each case, and we cannot confirm the verity of these allegations.”

Furthermore, Sharaf stressed that the UNHCR “does not divulge details of individual cases to the media for discretion purposes.” She notes that the organization has a “set system for reporting any abuse or mistreatments refugees might face,” and that “[we] strongly encourage refugees who encounter problems or instances of abuse to report such cases immediately and through formal routes so that relevant authorities within the commissioner can investigate and reach practical solutions.”

Sharaf elucidated the services the UNHCR provides for refugees and asylum seekers of “all nationalities.” These include the following: registration and documentation (granting yellow then blue asylum cards), legal services via the organization’s legal associates, and limited financial aid to the most vulnerable according to studies conducted by the commissioner itself — in addition to primary health care, urgent or emergency care, specialized care, and treatment for chronic disease patients in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and local affiliates.

The UNHCR also issues academic grants for children in public schools as well as specialized and dedicated services for refugees who have suffered harsh circumstances in their homeland, or on the arduous journey to the host country. These services include legal aid along with mental and social support supplied through specialized associates to vulnerable groups such as unaccompanied children (those without their parents/guardians), the elderly, individuals with special needs, and victims of physical abuse or gender-based violence, among many.

Racism, homophobia, transphobia, prejudices, and lack of transparency...Refugees reveal incidents of “mistreatment” and “manipulation” in Egypt’s UNHCR offices, which in turn refuses to comment on “specific cases and instances”

Furthermore, Sharaf notes the UNHCR’s provision of seasonal services like the winter relief aid, which is an annual contribution to the most impoverished refugees. She also mentions that the UNHCR in Egypt supervises one of the “largest resettlement programs,” stating that “ a total of 2,478 refugees were considered for relocation in 2020, while 2019 saw 4,617 refugees apply for relocation in 12 countries and 3,995 refugees leaving for the resettlement country.”

She indicates that “refugees’ status are revised every once in a while to update cases or close them if need be.” According to Sharaf, “the prospective period for resettlement differs with each case and according to the conditions and procedures of host countries which make the rules and specify the numbers and categories of refugees they will be accepting.” Among the reasons that render a case closed is the refugee’s “desire to return to his/her home country, for instance.”

With the Exception of Palestinians?

As we have seen, the case-file for Shaker and his family on the official website of the UNHCR in Egypt reads “complete” — that is, qualified for resettlement. Yet, responding to Raseef22’s inquiry about the status of Palestinian refugees, Sharaf, in two separate emails, reiterated the following: “The UNRWA is the authority responsible for the affairs of Palestinians and their conditions, and it is entrusted with issuing press statements in this regard.”

This comes despite another three contradictory pieces of the puzzle: Shaker had shown us his blue asylum card issued by the UNHCR office. He assured us that all procedures and interviews conducted with him and his family happened within the confines of the UNHCR HQ and had no relation to the UNRWA, since the latter does not run relief aid programs in Egypt, nor does it offer services to Palestinians. Finally, according to the UN, the UNHCR is authorized to help Palestinian refugees outside the jurisdiction of the UNRWA, as in Egypt, for instance.

When Shaker and his family reached Egypt, the wars hadn’t started in Syria nor Yemen, and there was nothing preventing Palestinian refugees from registration.

The first of the Palestinian family’s woes began when it failed to procure the “residency” necessary for transportation and obtaining regular jobs, as well as enrolling children in free public schools. Although issuing residency permits is a responsibility of Egypt’s state authorities, Shaker asserts that the UNRWA, despite knowing the extent of his dire conditions, did not send or put in an unofficial recommendation on his behalf with Egyptian authorities.

He proclaims, “Everywhere I apply to work, the employer remains anxious that I do not have a residence permit. I am constantly subject to bad situations at security checkpoints for the same reason... Not to mention, the exploitation of my circumstances to make me work longer hours and for smaller pay. Oftentimes, I cannot even find a job.” Shaker also says he cannot change his residential area because of the residency, especially after everyone in the neighborhood has gotten to know him and his family’s good behavior and overall amiableness.

Owing to the fact of not owning a residency permit from Egyptian authorities, Shaker might be subject to paying a hefty fine at any moment if the authorities arrested him and so demanded.

Furthermore, the Palestinian refugee accuses the organization of “swindling him,” “stalling,” and “backing from its promises,” in addition to giving him false hope by telling him things then denying doing so and “nominating his family’s case file for resettlement years prior and without his knowledge.” He also claims that the UNHCR’s office refuses to put in a good word with Egyptian authorities to ease his bureaucratic proceedings and grant him temporary residency, because “he is a Palestinian refugee.”

To Raseef22, he recounts how the head of the commissioner’s office tried to “trick” him 5 years ago when he went to renew his family's refugee asylum cards, since blue asylum cards need to be renewed every 3 years. Yet, the office employee took the family’s expired refugee asylum cards unjustifiably and told the family that asylum permits for Palestinians cannot be renewed on instructions from the Egyptian government. Nevertheless, Shaker insists that his problem is not with the Egyptian government and believes that the UNHCR is “playing” him and using that claim as an excuse.

Shaker was able to get out of his predicament through direct intervention on his behalf from one of the heads of office and from an international relief organization working in Egypt that took pity on him and his family's situation and their rights as legal refugees. Only then did he and his family receive completely new refugee asylum cards.

A short while later, Shaker received a call from the UNHCR asking him and his family’s attendance for an interview regarding resettlement. He left the interview with the promise of a response within the next 2 to 4 months. It is now 4 years later, and he has not yet received any word.

In its response to Raseef22, the commissioner office refused to specify a certain time frame for the resettlement of asylum cases that meet all conditions and requirements, insisting that “every case differs from the other.”

Shaker lost all faith in the international organization that is supposed to honor and uphold human rights, especially that of his children to education. He claims that the long years of “non-transparency” drove him to document all the negative actions conducted by Egypt’s UNHCR office. Among these are the phone calls with contradictory stories and false promises that Shaker will be providing should the commissioner's office take any inhumane action against him or his family.

“It’s All with Love” and “Wasta/Nepotism”

Months have passed since Wael Ali — a member of the Yemeni LGBT community and a refugee — recently arrived in Egypt after being registered and awarded the “yellow card”. During this period, he was robbed twice and conned a third time by the landlord of a property that he had stayed in for some time.

When things became tough, he contacted the UNHCR to aid him in reaching a safe residence — without any financial assistance — since he had also received death threats from his family, whose members live in Egypt.

Wael was being frank when he told the organization’s officials at the time that he had the money to pay for his housing, but that he only needed guidance for fear of being conned again. Following a meeting to discuss his assistance, the UNHCR official turned him down on grounds that he was “undeserving of assistance”.

When I went in, the worker asked me why I was there. I said ‘I’m a lesbian’. She yelled ‘What lesbian!’ and threw the papers in my face, demanding I leave the office. I didn’t know what she meant, but I felt fearful of the place I came to seek safety in

At the time — according to him — he resorted to a friend that works as an independent human rights expert with the organization, and, from there, things moved very swiftly. He told Raseef22, “As soon as [the expert friend] called me, I found them calling from the organization and asking what I wanted and asking me to go to the resettlement interview.”

A friend from the LGBT community facing nearly similar circumstances als0 came along with Wael. They went through the same steps and measures together, and Wael would take him with him every time to the resettlement interview. However only Wael received a call over the outcome of the interview. He thinks it is due to the “cronyism/nepotism” from his expert friend.

He tells Raseef22, “They say that they provide numerous services: health, housing, education, nutrition, and psychological rehabilitation… I have not seen anything of those. The simplest and most essential thing I needed from them was my protection in times of danger. I was shocked that when I asked for this, they shamelessly said, ‘We will not be able to protect you. What we can do, if you get caught and deported, we will stop it’, but becoming homeless or getting killed, they do not protect you from those.”

He adds, “When I had money, I did not ask them for help. And when I needed it only once [during the span of two years], they told me that financial aid (600 Egyptian pounds / 38 US dollars) was waiting for me at any post office,” wondering, "What does one do? I had expected that I would live a simple, decent life with the help of the UNHCR.”

“Racism”, “Homophobia” and “Transphobia”

Wael complains that upon contacting a legal institution from the UNHCR’s local partners, he was exposed to “blatant homophobia,” explaining that, “Someone who was supposed to be a lawyer called me. He asked me ‘your name is so and so’. I said yes. He said, 'You are a homosexual’. I said yes. He said, ‘Oh. yes, yes gay means LGBTQ community.”

Due to the constant death threats from his family, Wael questions every person that calls him, always asking for proof of identity — more than any ordinary person would. “I asked him several times what his name was, and what proof is there of him being a UNHCR lawyer. But he spoke in a rude manner and was constantly yelling at me. He would also leave me on the line for more than 10 minutes at a time, talking to someone there and then returning to the line to talk to me. When I asked him to end the waiting, he loudly cried out, ‘Am I not the one calling? Isn’t this from my own balance? Just be quiet’. I could do nothing but be quiet indeed.”

At the end of the call, and after he acquired all the information he had requested, the lawyer told Wael, “Currently, we will not be able to help you, but I will connect you to the specialist (social worker) to see what we can do for you.” The call with the social worker was not really better in any way, according to Wael, who said, “She seemed more friendly and told me her name, so I felt instantly better, and then her first question shocked me to the core: ‘Did you come to Egypt in order to get a sex change?' I felt my whole world spin around me then, not just because of the ugliness of the word and that it was transphobic, but also because it brought back my entire life flashing before my eyes... all that I had suffered.”

He continues, “What is more painful is that, in the end, she said to me, ‘We cannot help you’. Then why did you call?”

Three years ago, Haneen and Riham, two gay Yemeni refugees, fled to Egypt from Saudi Arabia, where they were born and had lived for most of their lives. When members of their families arrived in Cairo to find them, they headed to the UNHCR. “We thought that the organization would provide us with immediate protection, since the threat posed to us was imminent and dangerous. We were surprised when we found ourselves standing in line at the door, unable to even enter,” Haneen tells Raseef22.

The first visit only resulted in a filled-out form and them leaving with a promise of contact sometime soon. What happened next disappointed them even more, according to Riham’s account. She goes on to tell Raseef22, “At the outer gate, your eyes rejoice when you read the words: ‘A place where you don’t find discrimination’. As soon as we entered, the employee asked me what my story was, and I told her I [name] am an atheist. She looked at me, and it seemed that she did not like my words and replied: ‘Alright, alright, just wait for your turn’.”

When it was their turn for the next stage, they were called upon with their file number. Haneen had filled out one form for herself and her partner, which she thought was normal, considering that they were “family”. The employee responsible for registering their data asked, “Are you family?” Haneen replied, “Yes, this is my partner.” The employee then said, “Do you not know what the meaning of a family is? What type of education did you get?” Haneen tells us, “I was supposed to feel completely comfortable talking about my homosexuality and my partner… I assumed in advance that this was respected in this place in particular... Instead, I felt afraid of her stance, and my partner had to leave the office and submit a separate application.”

Riham intervenes here and explains that what happened to her was even worse. She says, "When it was my turn and I went in to the employee, she asked me — as per usual — why I was there. So, I said, ‘I am a lesbian’. She yelled loudly, saying, ‘What lesbian!’ and threw the papers in my face, demanding I leave the office. I did not know what she meant, but sadly, I felt fearful of the place I had come seeking safety in.”

Because of what he called an “unpleasant view of LGBTQ people inside the UNHCR building,” Hazem Abed — a gay Sudanese refugee — applied for asylum as an atheist without referring to his homosexuality in any way.

In addition to all this, four of our sources said that they had witnessed or were subjected to incidents of “discrimination” within the commission as well as both its religious and legal aid associate organizations. One of them retells, “Staff and guards there treat people [the refugees] as if they are ‘cattle’ with no dignity and without any respect for their suffering, in stark contrast to human rights standards... They demand commitment to all the things that they don’t even do.”

As for “the racism towards black people is abhorrent. Security personnel deal with black asylum seekers in an extremely horrible manner as if they are not humans. This is evident from the looks and behavior directed at them; they tell them not to touch them and to keep their children away,” he adds.

“No respect for Humanity or Trauma”

Hazem accuses the organization’s work force of unprofessionalism and abandoning humane treatment during pre-registration interviews, describing them as “inquisitions”. He clarifies, “When I was recounting what I had been through of persecution and rape as a child, I was devastated and reliving the pain in the same intensity that I had felt it the first time around. They showed no sympathy, rather, asked for more details. All they care about is checking your story with no regard to your suffering.”

He adds, “There is no professionalism in handling risky cases, nor is there any respect for humanity or trauma; no hot or cold line... They do not respond, and even if they did, it is not to help or interact even.”

Hazem divulges to us, saying, “I contacted them twice with suicidal thoughts. the clerk replied: ‘I don't know what to tell you but try to partake in our activities and occupy your time’.” He also told the commissioner’s employee of two incidents of sexual harassment in the Metro and by one of his neighbors, to which she responded with: “Try not leaving the house.”

Wael, for his part, has a lot to say about the pre-registration interview process. “I had anticipated them showing cooperation or sympathy with asylum applicants, especially since they are made privy to the tragedies of their lives. When I was retelling the circumstances of my escape and my reasons for seeking asylum, I was in a dire mental condition; I couldn't breathe properly. No one told me ‘enough for now’ or ‘rest a little’. No, you are to continue, or your application will be rejected.”

“The employees and guards there treat refugees like ‘cattle’; with no dignity and no respect for their suffering — in a blatant contradiction to human rights standards.” Not to mention “Racism towards black people is abhorrent”.

Haneen recounts a similar story. She says, “We were threatened a few times during our stay in Egypt. It forced us to move our residence 5 times. We called them several times to no avail. The one time they did answer, the response was ‘miserable’. The employee said: ‘Did anyone come for you? Did anyone say they would kill you?’ The response makes you feel like they are waiting for your death to move a muscle for your burial.”

Reham states that she was subjected to a “demeaning” investigation and was “emotionally drained,” because her siblings — whom she had fled from in the first place — belong to terrorist groups. She explains, “They told me my case was ‘in the bag’, and that my situation deserves prioritization for resettlement, and that I will be travelling to France. Then, they called me again and apologized for not going through with the process because my brothers were terrorists. I told them ‘my brothers are terrorists, and I am afraid of them. Do you want me to remain in danger?’”

She then exclaims indignantly, “The UNHCR now suspects me… Me, the atheist lesbian fleeing her brothers’ oppression. The UNHCR cannot protect me and has left me to my fate [to the vultures].”

Moreover, three of our sources made claims of sexual and physical harassment of refugees within the UNHCR HQ in Egypt, without following up those claims with proof.

“No Transparency”

During a specialized rehabilitation training for refugees organized by a religious relief organization in Cairo for the UNHCR, Wael said that all the refugees he encountered and spoke to did not know their fate, nor could they know when they might be resettled. He claims that the trainer in the event — that was aimed at enabling them to acquire job opportunities — is a refugee herself and has not had the opportunity to be resettled even though her file is complete and she’s been in Egypt for about 15 years.

He adds, “There is no transparency. They do not tell people about their status or when they might travel or how long they might have to wait. Even the trainer publicly described the UNHCR to us as a ‘fancy, top-tier organization for human trafficking’, meaning a trafficking organization that’s dressed in an official suit and tie. They just choose whoever they want to pass through and allow travel.”

Two of our sources say that the organization’s security guards form a “gang” with “agents” and “exploit” refugees and asylum seekers, since only those who “pay” are allowed to pass through or answer a call.

Three sources said that the renewal of refugee asylum cards — that takes place every three years — would be delayed for months or perhaps a year. Without a valid card, the refugee is under risk of arrest and deportation, and he/she cannot receive any remittances or deal with any official parties.

At least two of our sources told us that they repeatedly sent complaints via e-mail to the parent organization in Geneva of alleged violations in the UNHCR in Egypt and did not receive a response.

Terror…

Hazem says that the UNHCR employee that communicates with him threatened on two separate occasions to close his file and confiscate his asylum papers under the pretense of him being “uncooperative” and “not wanting to help himself”. The first was for missing a job training program organized by the commissioner when his brother was in Egypt, and Hazem had informed her he was agoraphobic. The second was for not visiting one of the psychiatrists affiliated with the UNHCR office despite Hazem reiterating to the apathetic employee that he had tried to contact the psychiatrist several times to no avail or any response.

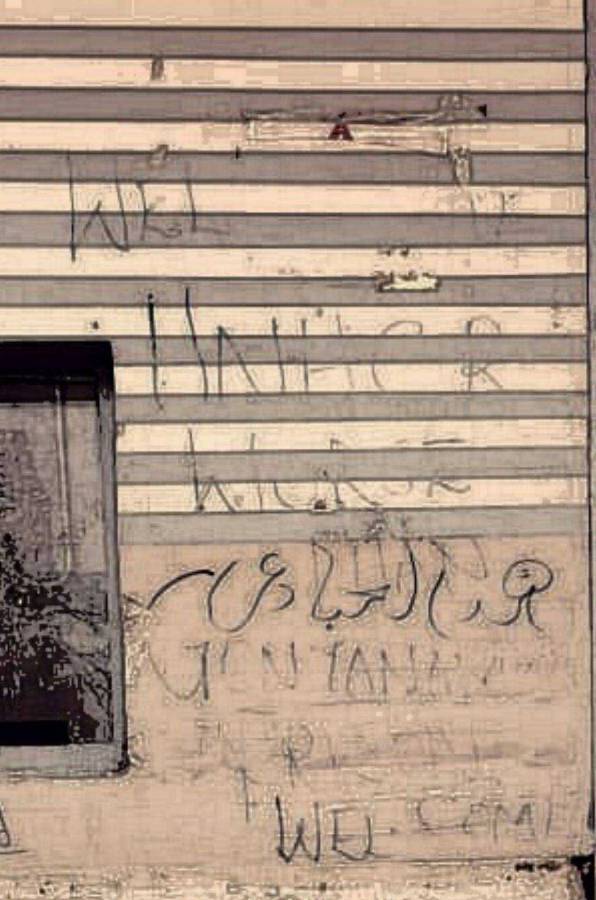

Hazem shared with us a picture he took of a phrase spray painted on the outer wall of the commissioner’s office. The statement reads, “Well, UNHCR [is] worse than my country’s state prison.”

Two other refugees retracted their statements after speaking to Raseef22 and asked for their testimonies to be withheld from the article in fear of their identities getting exposed and suffering further harm or repercussions from the organization’s officials. Those who consented to publishing their statements insisted on redacting any personal information that might mark their files with the commissioner. Therefore, all the names mentioned above are aliases.

“When I was recounting the reasons seeking asylum in Egypt, I was in a dire mental condition; I couldn't breathe properly. No one told me to pause or rest a little... No, you are to continue or your application will be rejected.”

On Facebook, there have been comments that consolidate our sources’ claims. On a Mother's Day celebratory post (by UNHCR Egypt), one user writes, “Of course, you are sympathetic to mothers, that’s why you stopped financial relief from reaching needy, deserving people and kept the aid running to shop and factory owners.” Commenting on a post about organizing an sporting event for refugees and their children, another user writes, “By God, our children are fit to burst being stuck at home, while events and activities are held for the friends and relatives of those running the organizations.”

Responding to these allegations of procrastination and stalling on promises brought forth by refugees, Sharaf says, “We are fully aware of the hard conditions refugees have been suffering from, especially after the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, but the UNHCR is exhausting all efforts to accommodate refugees and asylum seekers in Egypt. It has also worked on using alternative means to continue servicing refugees following the spread of the pandemic,” noting that “the commissioner had to downsize these programs for lack of resources.”

Sharaf stresses, “Everyone contacted for eligibility to certain services are receiving them. But limited funding to the commissioner creates a difficult challenge to providing preventative services and sufficient response. The [UNHCR office] is providing a number of services, first of which is registering and stating the status of the refugee, because that protects him/her from deportation.”

It is worth mentioning that all the individuals we spoke to denied being mistreated or subjected to any harassment by Egyptian authorities. Furthermore, the commissioner informed us that “the Egyptian government works tirelessly to ensure the safety of refugees on its soil. Respective authorities exhaust all efforts to provide support to refugees and asylum seekers of all nationalities in Egypt,” especially in regards to the health and education sectors.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!