I keep thinking about some post cards I bought during my last visit to Beirut, before the apocalypse of August 4. They were “old” black and white photographs, some of destroyed buildings in downtown Beirut which at the time was a frontline in the Lebanese civil war. The others were of a Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut’s suburbs during the Israeli invasion of 1982. I bought those cards from an elegant bookshop in Gemmayze, one of Beirut’s districts that was badly hit by the port blast on August 4.

I bought them because they seemed beautiful to me and somehow romantic, symbolising the message of hope from a city that always has been able to resuscitate itself. It saddens me now to think that the bookshop may be one of hundreds of little boutiques and businesses destroyed in the blast that claimed 178 lives, injured thousands and made more than 300,000 homeless, according to the UN Refugee Agency.

When I bought these post cards I thought that the cycle of destruction in Lebanon was a thing of the past. I thought that peace, although fragile, was now an established reality, and homes and apartment buildings would stand in mute testimony of normalcy. Never did I imagine what was to come and what it would mean.

It is now one year since I visited Beirut. At the time, the city was buzzing with a hopeful revolutionary vibe. Loved as an almost imaginary country, we Lebanese always ignored Beirut’s ugly faces while feeling nostalgic for a city we know is vanishing

As a regular “migrant” visitor from London, where I now live, I liked to revel in the sense of Beirut as the city of renewal so much so that I would almost always book a room in a hotel in the Hamra district of West Beirut because it overlooked the infamous Holiday Inn, the bullet-riddled and rocket-pock marked building that is a symbol in our collective memory of a brutal civil war that destroyed huge swathes of our humanity. The Holiday Inn was at the centre of the so-called “war of the hotels” between Christian and Muslim militias that lasted more than a year, leaving more than 1,000 dead and 2,000 injured. From the narrow balcony of my hotel room, I used to enjoy my morning coffee while contemplating the scarred Holiday Inn building as symbol of resurrection and hope for Beirut and all humanity.

As part of my more recent remembrance rituals, I added the newly opened Museum of Civil War. Located on a cross street known as the "intersection of death” during the civil war, the yellow building that is home to the museum, an elegant house of ottoman architecture, was once a base for snipers looking to clip short the lives of passengers who dared to cross the so-called the Green Line that divided East and West Beirut. While the interior has been refurbished, the bullet holes and graffiti have all been preserved, as homage of the war’s daily routines. The civil war that erupted in 1975 between Lebanese Christian right-wing militias and largely Muslim Lebanese and Palestinian progressive factions, took the lives of a quarter million people. It ended, in 1990, with the Taef agreement that established a new power sharing structure between Lebanese sects.

The port blast that reintroduced the horror of fire, rubble and twisted metal to Beirut was not an episode of war or even part of its aftermath. It cannot be linked to the narratives of civil conflict or its symbols that have become part of Lebanese identity and created a kind of romantic connection with the past.

I like to remember with sense of sweet nostalgia the years of the so called “reconstruction” in the 1990s. The fall of the “imagined” borders between East and West Beirut was celebrated as the start of a new era. I recall as a journalist taking the collective taxi known as the “Service”, crossing between the two sides of the city, venturing into once “dangerous” territories and interviewing people about their experiences of meeting compatriots who used to be the “enemy.” Battlegrounds became hubs for clubbing. I remember this popular little bar in Monot Street that was plastered with symbols of the war: pictures of guns, graffiti of militiamen, and songs of Ziad Rahbani, the son of the iconic Fairuz, who translated with sarcasm the plight of the Lebanese during these tough years. You could order “Kaeke” - a dry dough- a staple during the dire economic realities of the war, although today they seem small compared to the current economic woes the country is living through. According to UN agencies, half of the Lebanese now live in poverty as a result of the recent financial collapse.

Sitting safe in my London flat, I contemplate memories of my “romantic” Beirut, all my years loving it and hating it. I am filled with the anxiety of dealing with the next possible tragedy and wonder if I can ever really go back there

Like other Lebanese migrants, I kept watching the videos of the port blast, some taken from inside homes that were all but demolished by the explosions. I would watch them over and over. There is nothing “romantic”, symbolic, hopeful or meaningful in this destruction. It is a horrible random event that simply underscores unbearable frailty of our lives. We used to accept and even celebrate this fragility as well as our acts of defiant resilience as a sign of Lebanese exceptionalism. Today, I follow the news of those who are leaving or trying to leave the country desperate to rebuild their life abroad because there is little to look forward to in Lebanon. People have little hope that those responsible for the crimes that led to the latest tragedy will ever be held accountable or that the endemic corruption will end.

Like millions of other expatriat Lebanese, I would visit home at least once a year, and I feel terribly sick that I will not return this year. I bought a pied a terre in Beirut, something many of us living and earning abroad have done, though I now have no idea what its future will be. Sitting safe in my London flat, I contemplate memories of my “romantic” Beirut, all my years loving it and hating it. I am filled with the anxiety of dealing with the next possible tragedy and wonder if I can ever really go back there.

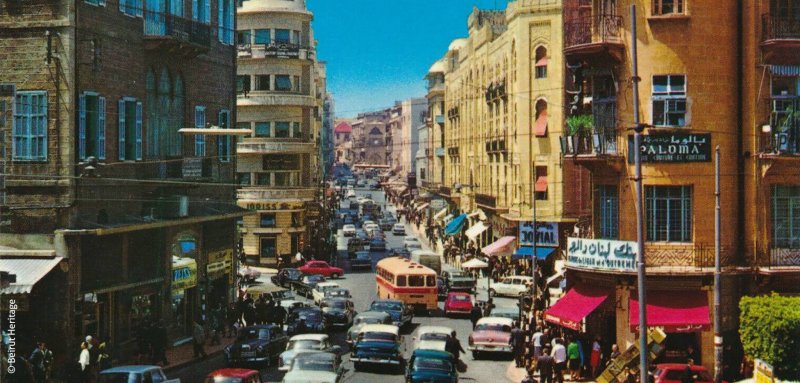

It is now one year since I visited Beirut. At the time, the city was buzzing with a revolutionary vibe that was painfully hopeful. Loved as an almost imaginary country, we Lebanese have always liked to ignore Beirut’s many ugly faces while we feel nostalgic for a city that we know now is vanishing. Many of the destroyed buildings in historical Beirut can turn into new postcards for an unfolding destruction. I fear if nothing changes, all that will be left is little more than fading memories and postcards.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!