Sitting in her front balcony, 24 years old HM dwells over her shattered dreams of pursuing a career in media. As a young graduate of Media Studies, she worked as a correspondent at an independent satellite media channel, an ambition she’s pursued since she was a teenager. Soon after that, however, she had to resign having been sexually harassed by her boss. She filed a complaint to the senior director, as a result of which she was dismissed from her job and is currently unemployed.

HM recalls, “after graduation, I joined a well-known media channel. One day as I was going into the recording room, my boss followed me and closed the door behind us. He got close to me and tried to hold my neck. I grabbed his hand and asked him what is it that he wanted. He said I want to sleep with you, so I pushed him away and complained to the Director, who blamed me for the incident. My employment was terminated and the harasser is still employed until this day”.

HM is still trying to overcome her new trauma, she had endured the loss of her father in a terrorist attack in 2006. She is struggling to accept the loss of her job, and having to give up her dream of pursuing a career in media for fear of facing a similar experience.

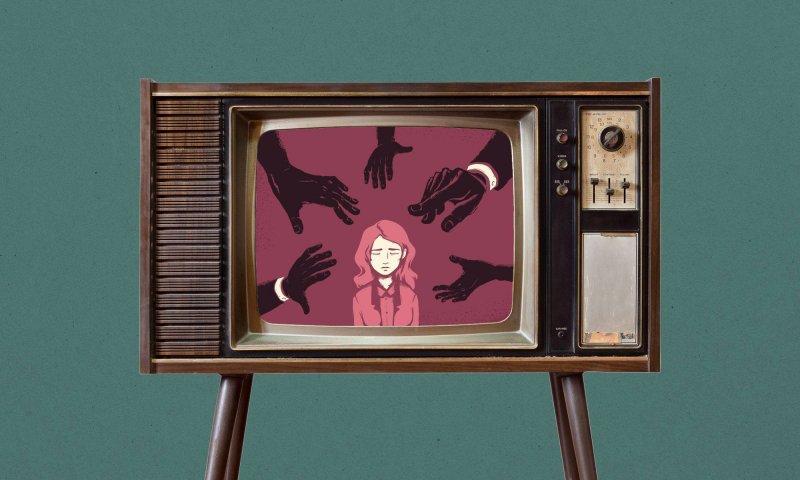

Stardom For Sex

Behind the glitz of media and celebrity in Iraq lay secrets that few people want to speak about. Many women who work in media suffer similar incidents but prefer not to speak out. They feel that speaking out against sexual harassment and abuse may jeopardize their career and instigate social stigma and shame on them.

Unlike HM, who preferred to disguise her name, Amira Al-Jaber chose to speak out about her own experience of a similar incident by the manager of the media channel where she was employed.

Amira says, “I worked my way up to become an anchor at a TV channel in Baghdad. One day the manager invited me to his office and asked me directly to have an affair with him. I vehemently refused, so he put a halt on the program I had presented and fired me”.

Al-Jaber is certain that her chances of working in media are limited now because of her audacity in exposing the abuse and blackmailing she was exposed to. Despite complaining to the police and providing evidence against one of the perpetrators, “little has been done against the harasser because he was the son of a politician. The police did not do anything even though he refused to pay my salary for the last two months of my work”.

She continues her search for another job being the sole provider for her daughter and mother. However, sexual harassment by seniors at work remains a cause of anxiety and worry for her. Meanwhile, she continues to raise awareness among women about harassment at work, especially in media, and the need to speak out against abuse, sexual harassment and the need to expose perpetrators.

Amira Salah was fired after complaining of being sexually harassed at a state-owned TV channel. After appealing, she was reinstated as TV anchor, however her harasser threatened to shoot her in the legs. Half the women in #Iraq are harassed at work.

Public Harassment In Public Channels

In addition to private and independent media channels, government funded media outlets seem to have lax procedures against sexual harassment at the workplace. Ann Salah is a 34 years old presenter at Al-Iraqiya TV channel. She faced a similar fate to other working women when one of her seniors harassed her and fired her as a result of raising a complaint against him. “I worked my way up from a correspondent to a TV anchor at Al-Iraqiya public broadcaster. One of the bosses was harassing me constantly. At first, I tried to stop him without escalating the matter, but he didn’t stop. I had to get a proof of his advances, and when I did I took it up legally. I recorded one of his calls and presented it as evidence before the Board of Trustees of the Iraqi Media Network. An investigation was initiated, and as a consequence he was transferred to another position where his powers were largely curtailed. However, a month later my job was ended without notice as an act of revenge”.

Salah appealed against her unfair dismissal and was admitted back to work as an anchor. When she met her harasser a few months later, he blamed her for complaining against him and threatened her saying “I’m a man of influence, and I can hire someone to shoot you on the legs- you’ll be disabled for the rest of your life”.

Although Salah still keeps her job, she is emotionally and psychologically overwhelmed by the harassment and threats she received. She believes she was able to speak out and face the consequences because she is strong willed, however she says that not many women who work in the media are capable of doing the same for fear of being judged at work or by society at large, or for fear of sacrificing their job and reputation.

In 2012, a study on violence against women was conducted by the Iraqi Women Journalists Forum. The study concluded that more than half of the women who participated in the survey were victims of harassment and that they chose to remain silent for fear of compromising their job and reputation.

Nibras Al-Mamori, head of the Forum, explains that “68% of the women who participated in the questionnaire were harassed, and that this finding made news in Iraq’s press at the time”. She adds that after the survey’s findings were published the Forum was heavily criticized by various institutions and personalities. According to Al-Mamori, “the report broke the silence about a taboo subject and was defaming to Iraqi women according to its critics, which eventually led to the survey being pulled from the spotlight”.

Denying a Common Practice

We approached the Federation of Journalists of Iraq, and we were told that the Forum’s findings and conclusions are not recognized by the Federation.

Sanaa Al-Naqash, a board member, says “we conducted a poll of our own immediately after the Forum’s findings were published, and we found that no more than 2% of women experienced harassment”, which explains why harassment is not viewed as a common occurence.

Al-Naqash adds that the survey included 200 journalists and media workers, who were asked 38 questions about the various issues they faced. Although the survey was anonymous, responses confirming harassment were minimal- 5 women said they were harassed, 4 women said they were verbally harassed and 1 woman said she was sexually assaulted”.

The Truth About the 200 Journalists

We conducted a new survey in which academic staff from various Iraqi universities were asked to distribute a questionnaire on 100 women who worked in media and journalism in different regions of Iraq. Results showed that 54% of women included in the survey said that they were victims of harassment, 67% said that they were verbally harassed and 22% said that they were sexually assaulted.

Findings of the survey also showed that 52% of women were harassed at work, while the remaining women were harassed through phone and social media. The majority of women chose not to report harassment for fear of losing their job.

On the other hand, findings for women who reported harassment to their employers indicated that no action was taken against the harasser in 35% of the reported cases, whereas in 30% of the reported cases a warning was given to the harasser, compared with 17% of cases where the harassers were dismissed.

This survey also revealed an important fact, namely that the victims of harassment choose not to confide in their families, and prefer instead to speak to a friend for fear that their families may ask them to leave work and stay at home. In addition to this, there were many cases where reporting harassment to employers had resulted in acts of revenge.

It was also revealed that 61% of women who participated in the survey chose to ignore harassment for fear of losing their job or being stigmatised, and that 36% of women preferred to tell a friend, whereas only 2% of women chose to tell their father or brother.

Harassment by the Police

Ezzat Akram, a human rights activist, explains that victims choose not to report harassment because “the harassment laws and provisions are often reduced by the authorities who are in position of protecting victims and stopping this phenomenon”.

Akram further explains that the role of the community police is not enforced properly. According to her, the provisions are available but are not enforced, and in some cases members of the police and army commit harassment”.

Despite breaking many social barriers, especially after the October revolution, many women in #Iraq remain reluctant in reporting harassment for fear of social stigma, being judged, blamed or even harassed by the police.

The Community Police

Brigadier Khaled Al-Muhanna, Director of Community Police at the time of the investigation, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Interior, admits that "harassment is growing due to the lack of awareness among some police personnel. The community police department was established in 2008 in order to address problematic cultural concepts such as harassment.

Al-Muhanna notes that "part of the problem is the fact that the majority of women are afraid to inform the police, their relatives or their employers". He adds that "the Ministry of Interior is planning to address the phenomena and educate the police in order to serve citizen in a better way".

Legal provisions

The Penal Code (1969) clearly states the different types of penalties and the types of harassment. However, these penalties are not applied for fear of stigma, according to legal expert Tariq Harb.

Article (396) of the Iraqi Penal Code No. (111/1969) states the punishment of imprisonment for a period not exceeding 7 years for anyone who sexually assaults or attempts to assault a male or female, by force, threat, manipulation, or any other means without consent.

It furthers states that, "If the victim is under 18 years old, or if the perpetrator pertains to paragraph (2) of Article (393), the penalty shall be imprisonment for a period not exceeding 10 years."

Article (397) also stipulates that “a person who sexually assaults an underage male or female without force, threat or manipulation shall be imprisoned. If the perpetrator of the crime pertains to in paragraph (2) of Article (393), the punishment is imprisonment for a period not exceeding seven years or imprisonment”.

Despite breaking many barriers, especially after the October revolution in Iraq in which a large number of women took part, many women remain reluctant in reporting harassment.

Whereas HM continues to wait for a way out, Amira chose to express her anger by taking part in the daily protest in the city.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!