“Egyptians have been subjected to hatred and aggression by the Persians, the Greek and from the Arabs, Turks and French.” Perhaps it didn’t cross the mind of the Dean of Arabic Literature Taha Hussein (1889-1973) when he wrote this statement Kawkab al-Sharq newspaper in 1933, that he ignited a debate that will linger for a long time. This statement would become the reason for the flaring of the biggest intellectual battle in the modern history of the Near East, a battle that would remain ongoing for a six consecutive years, with its flames reaching as far as the Levant and Mesopotamia.

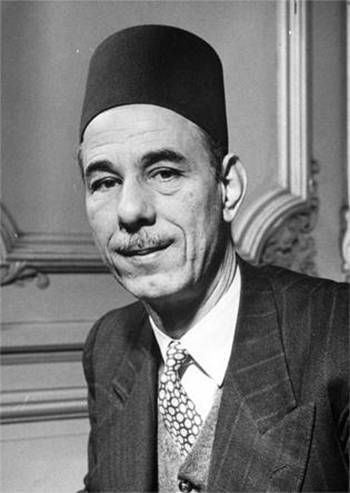

Abdul Rahman Azzam

The first spark of the battle was lit by Egyptian politician Abdul Rahman Azzam (1893-1976), who would later become the first Secretary-General of the Arab League. Azzam wrote an article titled “Is Egypt not Arab?” in the Egyptian paper al-Balagh, in which he responded to Taha Hussein - while recognizing his intellectual standing - and asked him to “offer some concrete incidents in which the Arab Muslims were violating aggressors.” Azzam went on to affirm the Arabness of Egyptians, declaring: “The Egyptians accepted the religion of the Arabs, the customs of the Arabs, the language of the Arabs, the civilization of the Arabs, and became more Arab than the Arabs,” adding: “And what we know from researching the ancestry [lineage] of some Egyptian provinces is that the majority of its peoples’ blood is derived from the Arab race.” Azzam denied that the current Egyptian population was a continuation of the ancient Egyptians, excepting a small portion, and said that the Egyptian nation was inundated with waves of Arab migration. Azzam concluded his article by criticizing all nationalist tendencies which contradicted Arab nationalism, writing: “What has remained of Assyria, Phoenicia, Pharaoh and Carthage other than what the Arabs kept within themselves and other than the living nation that extends now from the ocean to the ocean? For we today only affiliate ourselves to that living Arab nation that has inherited our lands.”

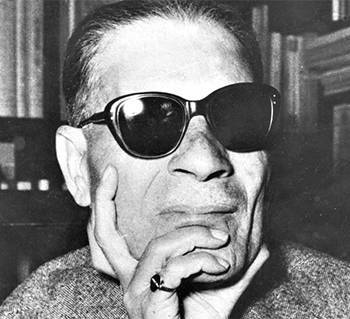

Taha Hussein

Taha Hussein responded to Azzam’s article with his own published in the newspaper Kawkab al-Sharq criticizing the al-Balagh newspaper that had led a fierce campaign against him. While denying that he was an opponent of the Arabs or a denier of their past glories, he wrote: “I am the last person who could insult the Arabs,” while adding that the history of Arab governance of Egypt was “like the Arab rule of all the Islamic countries, a mixture of good and evil, justice and oppression, and Egypt tired of it and revolted against it.”

Ibrahim al-Mazini

Taha Hussein’s latest article angered the Egyptian poet and novelist Ibrahim al-Mazini (1889-1949), who wrote an article published by al-Balagh criticizing Hussein’s logic of stigmatizing the Arabs. al-Mazini wrote: “The rule of humans by humans will [always] have good and evil and justice and oppression. Every nation be it old or new in every place on this earth has experienced these shades from its rulers.” al-Mazini concluded that Taha Hussein, not least in his last article, accused the Arabs of oppression, aggression and violations in their rule of Egypt.”

While Taha Hussein questioned the "Arabness" of Egypt, AbdelKader Hamza stated: For Egyptians there is a first homeland, and that is Egypt, and a second homeland, and that is Arab nationalism.

Academic Zaki Mubarak stated: "we are Arabs in language and religion, but are Egyptians in nationality", he believed Egyptians have their own culture which differs materially from Arab culture.

Taha Hussein claimed that the vast majority of Egyptians do not have Arab blood in them, but are direct descendants of the ancient Egyptians. As to the Arabic language, he repeated that a language does not appropriate a nation.

Abdul Rahman Azzam

Following Taha Hussein’s article, Abdul Rahman Azzam published a second piece in the al-Balagh newspaper expressing his faith not only in the Arabness of Egypt but the Arab nature of all of the Arabic-speaking countries. Signifying the Arabness of Egypt by pointing to the concept of its integration into the Arab nation and the roots of Arabness within it, he wrote: “Thousands of years have done their deed, the intermixing of the Arabs with the ancient Egyptians and their participation alongside the Arabs in the same lineage is testified by the strong similarities between Hieroglyphics and Arabic; indeed, the Arabs used to assert their relations [from the maternal side] to the ancient Egyptians centuries before the emergence of Islam.” Azzam then once again criticized all of the non-Arabist forms of nationalism in the region, stating: “Let then the advocates of Pharaoh in Egypt or Phoenicia in Syria or Assyria in Iraq go wherever they want; if they are able to enlist one village in the name of the nations that have become extinct amongst the people of the Arabs then they can establish their populism on a deep basis. As for the call in the name of the Arabs, it will awaken seventy million in Asia and Africa.”

Muhibb-ud-Deen Al-Khatib

The Syrian Islamic writer Muhibb-ud-Deen Al-Khatib (1886-1969) joined the ranks of Abdul Rahman Azzam, writing an article in al-Balagh titled “Arab nationalism and Egypt’s position from it” in which he affirmed the Arabness of Egypt, Iraq and Syria. Citing Ahmad Kamal Pasha’s dictionary of the ancient Egyptian language in which he “interpreted the language of Ancient Egypt with the language of modern Egypt (Arabic), finding Arabic expressions similar in both pronunciation and meaning to that of the ancient Egyptian expressions,” which al-Khatib cited as evidence of Egypt’s Arabness since antiquity. He thus wrote: “Ancient Egypt’s language is the language of the Arabian Peninsula with no differences between the two other than in deflections and some synonyms, for they are two dialects of the same language.”

Indeed, al-Khaitb even argued that the ancient Egyptian ruler Menes, the uniter of the two (Upper and Lower) Egypts, may have come from the Arabian peninsula. He then followed by declaring: “Is reviving the title of ‘Assyrians’ after being extinct for centuries, and reviving the Berber custom in North Africa, and publishing books of grammar and spelling for the Berber language, not episodes of the chain for the same decreed programme [for us], while we put our necks in the chain to suffocate in it… Should I point out that the [British] Administration in Palestine wanted years ago to revive the name Phoenicia and use it for the north-west district there.” al-Khatib concluded that the English and their instruments worked hard to “deceive the Egyptians, letting them think that the presence of Arabic and Islam in Egypt was but an occupation similar to the Persian, Greek, Roman, French and English occupations.”

Abdulqader Hamza

Next, was the article written by the Egyptian journalist Abdulqader Hamza (1880-1941) in al-Balagh titled: “Egypt is from the Arabs and nationalism and Arabic,” in which he wrote: “For Egypt there is a first homeland, and that is Egypt, and a second homeland, and that is Arab nationalism.” Taking one step backward, Hamza affirmed that he did not deny that “the Semitic component has been attached to Egypt for thousands of years, and when the Arabs conquered Egypt they gave it the Islamic religion and Arabic language and culture, but there is no denial that all of that does not detach Egyptians from their Egyptian nationality, their Egyptian environment and their Egyptian history.” Thus Hamza saw that the Egyptians were Egyptians in their homeland, nationality and history, and Arabs in their religion and language.

Meanwhile, Hamza criticized those Arabists who neglected the ancient Egyptian heritage preceding the Islamic conquest and ascribed only an Arabic identity to the country; stigmatizing their hatred of the memory of the Pharaohs who were commonly cited by Egyptians, he asked: “Is it logical that Europeans and Americans pay tribute to that past, with thousands every year going to visit their relics and antiquities, while Egyptians deny it or neglect it?” Hamza concluded declaring: “Egypt became Arabic in religion and Arabic in language since fourteen centuries ago.”

Fathi Radwan

The Egyptian intellectual and politician Fathi Radwan (1911-1988) joined the battle with an article published in al-Balagh titled “No Pharaohism and no Arabism after today” in which he criticized the two sides, because both “did not research using tools of scientific evidence, but chose between the glories of two civilizations and brought in religion into this comparison,” adding: “It was the duty of the researchers to confine their research to the Arabs and not to Islam, and should have compared the Arabs before Islam with the Arabs afterwards, and not only those before.” Radwan criticised those who combined Arabism with Islam, arguing that in so doing they abused religion. He concluded his idea by stating “Pharaonism and Arabism is a subject that should be abandoned because it entails within its formulation insults and shame. Shame that Egyptians disagree in this fashion in knowing their origins and ancestry. And shame that the voice of a great writer is raised deciding that Egypt is Pharaonic, while on the other side a voice of another great writer is raised deciding that it is Arab.” Radwan did not neglect to accuse colonialism of fomenting this strife, writing: “Most likely the responsible party here are the colonialists who want to divide Egypt’s history into two sections, thus spoiling the unified history of this great nation and dividing its sons into two quarreling and struggling camps.”

Salama Moussa

Next to join the battle was the intellectual and thinker Salama Moussa (1887-1958), who wrote an article titled “This Egyptian nation” strongly defending the call to Pharaonic culture. Indeed, Moussa was one of the most notable advocates of Pharaonism in Egypt, denying that his call was a reactionary one but rather a civilizational endeavor - while criticizing those who believed that the call to Pharaonism equated a denial of the Arabs or a return to the religion of the Pharaohs and their structures, arguing that such accusations were merely silly attempts used to undermine Pharaonism.

Zaki Mubarak

The battle flared up once again with the entry of the poet, writer and academic Zaki Mubarak (1892-1952) into the debating ring, with an article titled “The Arabic culture and the Pharaonic culture”, in which he criticized advocates of Egypt’s ‘Pharaonism’. Thus he declared: “The language of Egypt today is Arabic and its religion is Islam, so those who call for the revival of Pharaonism also call for the eschewing of Arabic and also call it to follow the Pharaonic doctrine in the fundamentals of religion.” In agreement with al-Khatib, he added that the Arabic language served as a “tool of understanding in the Nile valley for thirteen centuries,” adding “we are Arabs in language and religion, but are Egyptians in nationality” - though stressing “We are not tied to the Arabs other than by language and religion. Other than that we are the sons of this time.” Meanwhile, Mubarak rejected the notion of Pharaonic lineage, stating: “This is an illusory idea, for Egypt had integrated into Islamic nationalism and married [intermixed with] people of all races.” Mubarak further declared: “The Egyptian does not refrain from calling for Arab unity,” yet he nonetheless believed the possibility of political unity to be a remote and unlikely one. Mubarak followed his article with another one titled “Egypt’s culture must be Egyptian” in al-Balagh, in which he criticized those who assumed Egypt’s Arabness on a religious basis, putting religion to one side in this matter and prioritizing culture - declaring: “The issue has nothing whatsoever to do with religion, for the question is cultural.” Egyptians, Mubarak believed, had their own culture that differed from the culture of the Arabs.

Muḥammad Kāmil Ḥusayn

Next to follow was an article by the Egyptian physician and writer Muhammad Kamil Husayn in al-Sharq enwspaper, with the titled “Not Pharaonic and not Arab.” Perhaps the title was somewhat misleading, as it implied that the writer opposed both sides; in reality, he only opposed those who advocated Egypt’s ‘Arabness’. Husayn accordingly wrote that the nature of Egyptians, their lives and their mentalities differed from those of the Arabs. Furthermore, he criticized those who described Islamic culture as Arabic culture, believing that the former encompassed sciences and ideas that “were not Arab in anything.”

Sa’id Haydar

Next to enter the ring was the Syrian politician Sa’id Haydar (1890-1957), who was an activist concerned with Arabist causes and defender of the concept of Arabness. He wrote an article titled “Egypt is Arab” in al-Balagh. As the title implies, he was a defender of the concept of Egypt’s Arabness, and a critic of Taha Hussein’s call.

Taha Hussein once again

Professor Taha Hussein returned in 1938 once again to his opposition to Arab nationalism - indeed, even mocking the concept of Arab unity in statements made to the Lebanese al-Kushoof newspaper, as part of a debate between him and some Arab youth. In the conversation, Hussein insisted that Pharaonism was an innate part of the Egyptian composition and would remain so, and that the Egyptian was Egyptian before anything (else). He further claimed that the vast majority of Egyptians do not have Arab blood in them, but are direct descendants of the ancient Egyptians. As pertaining the Arabic language meanwhile, Hussein declared that if language had weight in determining the fate of nations, then countries such as Belgium, Switzerland, Brazil and Portugal would not have been founded.

Sati' al-Husri

In response to Taha Hussein, the Syrian intellectual Sati' al-Husri (1880-1968) wrote that Arab unity did not require Egyptians to surrender their Egyptianness, but to add to their Egyptian feeling a general Arabist one. He further denied Taha Hussein’s statement on the lineage of modern Egyptians being derived from ancient Egyptians, declaring that all scientific tests indicated that there are “no nations on the face of the planet that are pure-blooded.” al-Husri further criticised Taha Hussein’s statement that the history of Egypt was independent from the history of any other nation, declaring that the history of Egypt in fact intermixed on a deep-level with the histories of the other Arab countries, and was firmly affixed to it for the past thirteen centuries at the least.

Taha Hussein again

Professor Taha Hussein responded in the al-Risala newspaper in an article declaring that the unity of language gives rise to the unity of culture, and then the unity of mind - while nonetheless affirming that Egyptians cannot conceive of their participation in an Arabic empire, whether or not it was stable or permanent, and regardless of its forms or the type of governance within it. Regarding his attachment and guardianship of the Pharaonic legacy, Hussein insisted that the issue was not one of returning to the religion of the Pharaohs, speaking in the ancient Egyptian dialect, or recreating Pharaonic rule; rather, the intent was to consider this history with both its positive and negative aspects as an integral part of Egyptian lives and a component for Egypt’s unity as well as a component of its nationalism - in which “it can be proud of what calls for pride, can be pained for what calls for pain, can learn the lessons from what should be learnt from and can benefit from what should be a source of benefit.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!