As the sword of Ali ibn Abi Talib shattered during the Battle of Uhud, the pagans started to close down on the Muslims, leading most of them to flee, before moving in to try and finally kill the Prophet Muhammad.

It was at this point that the Prophet furnished his cousin Ali – also the Prophet’s revered companion, the fourth of the Rightly-Guided (Rashidun) caliphs, and a central figure in Shia Islam (Shia is short for Shia Ali, meaning ‘Partisans of Ali’) – with his famous sword, Zulfikar.

Ali proceeds to brandish it and strike down the valiant and brave warriors of the Quraysh tribe. Their attempted assault on the Prophet is successfully repelled, leaving the Quraysh foiled and routed, and what would become a famed utterance attributed to the archangel Gabriel reverberated in the skies: “There is no hero like Ali; There is no sword like Zulfikar.”

It is this epic and miraculous saga which introduced the sword of Zulfikar into the Shia collective consciousness, little-by-little acquiring a distinct symbolism and meaning(s), enabling it to eventually occupy a vital standing in both the political and intellectual domains of the various branches of Shia Islam.

Zulfikar in Sunni and Shia sources

Historical narratives have differed surrounding the origins of the designation of Zulfikar as the sword of Ali – as well as the circumstances by which it ended up in his hands.

Despite the more central position of Ali within Shia theology, an examiner of the historical texts of medieval Islam nonetheless find many mentions of Zulfikar in Sunni writings; these notably feature in the renowned ninth-to-tenth century Persian scholar Ibn Jarir al-Tabari’s celebrated works the “History of the Prophets and Kings”, as well as the eighth-to-ninth century Iraqi scholar (and founder of the Hanbali school of jurisprudence) Ahmed Ibn Hanbal’s “Virtues of the Companions.”

In these sources, it is relayed that the Zulfikar was acquired as part of the spoils of the Battle of Badr, in which the Muslims emerged victorious against their pagan enemies, and would be subsequently gifted by the Prophet Muhammad to Ali during the Battle of Uhud. With the Muslim army facing defeat, with many of their number abandoning the Prophet to face the pagans alone, it would be Ali who would take up the sword and push back the pagan attempt to strike the Prophet: killing and wounding many of the attackers and removing their danger from the Prophet’s immediate vicinity.

It is at this point that some accounts report following Ali’s successful defence, that a call from the skies by the Gabriel proclaimed a famous phrase: “There is no hero like Ali; There is no sword like Zulfikar.”

Yet despite the renowned and established nature of this narration, many Sunni scholars would subsequently agree to weaken its authenticity: as demonstrated by the likes of the celebrated 12th century Iraqi jurist Abd al-Rahman Ibn al-Jawzi, in his “Great Collection of Fabricated Traditions”, as well as the renowned 14th century Syrian exegete and historian Ibn Kathir, in his major works “The Beginning and the End.”

Indeed, it can be noted here that in their collections, such sources cited other lesser-known narrations; one such example attests that the Prophet had granted the sword to Ali during the Battle of the Confederates (also known as the Battle of the Trench) when Ali stepped forward to a duel with an enemy who had a reputation at the time as one of the bravest Arab knights.

On the other hand, if we examine the Shia narrations on Zulfikar, we find that they tend in their majority towards ascribing supernatural and miraculous attributes to the sword.

Thus, according to some narrations cited by seventeenth century Persian cleric Mohammad-Baqar Majlesi in his “Seas of Light”, the sword originally belonged to God’s first creation, the Prophet Adam, and was manufactured from one of the trees in paradise. When Adam would descend down to earth following his expulsion from heaven, according to the narrative, he would take the sword with him and use it to fight his enemies from jinn (supernatural spirits) and shayatin (demons).

Eventually, the sword would pass down from Adam through his progeny and the sequence of prophets and messengers that followed before finally reaching the hands of the Prophet Muhammad, who would in turn grant it to his cousin Ali. The narration also proclaims an inscription written on the blade of the sword, reading: “My prophets continue to fight with it, prophet after prophet… until the Commander of the Believers inherits it and fights with it on behalf of the illiterate prophet.”

Majlesi further affirms the famous proclamation about Ali and Zulfikar attributed to the archangel Gabriel during the Battle of Uhud; such a position is in keeping with the centuries-long practice of Shia resurrection of the phrase, and disregards the weakening of its authenticity by Sunnis.

Meanwhile in his “Virtues of Abi Talib’s Household”, Shia scholar Ibn Shahr Ashub writes that the eighth Shia Imam, Ali al-Ridha, interpreted the reasons for the sword’s special and singular significance to some of his partisans and followers in his declaration: “Gabriel had descended with it from the sky.”

Ultimately, these are only some of the claims which have been made surrounding the origins of the sword; others include the narration that Gabriel had created it out of the remains of a great pagan statue (idol) he had smashed in Yemen – while another account attests that the sword was one of many valuable gifts sent by the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon during biblical times.

In the same vein, some books have attributed the supernatural qualities of the sword to the Prophet Muhammad himself, whereby it is narrated that the Prophet took a palm frond blew into it, only for it to transform in his hands into the sword of Zulfikar.

As for the origins of its name, some Sunni sources attribute the title Zulfikar to some of the inscriptions present on the sword. Shia clerics on the other hand interpreted it in a variety of ways: sometimes as a description of the sword’s shape – as in the narration attributed to the sixth Shia Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq: “The sword of the Commander of the Faithful [Ali] Peace Be Upon Him was named Zulfikar because in its middle it had a design in its length similar to the vertebrae [fiqar] of the spine” – while the name is also sometimes understood to be a reference to its moral significance, with the aforementioned Ja’far al-Sadiq also purportedly declaring: “It was named Zulfikar because no one struck by it by the Commander of the Faithful was but deprived of his life in this world and from paradise in the next [afterlife].”

Political symbolism

Throughout the ages, Zulfikar would enjoy an important political symbolism and significance amongst Muslim politicians in general, and Shias in particular. Most Shia sects were keen to proclaim their rightful ownership of the sword, believing that its possession entitled its owners to the Imamate – as successors to the Prophet Muhammad’s leadership of the Muslim Ummah or community.

This concept was in no small part prevalent due to the widespread narrations which spoke of Ali’s use of Zulfikar during his wars and battles against the rebels who opposed him during his leadership of the Muslim community (from 656-661 AD, as the fourth caliph or successor to the Prophet).

It is reported that Ali used the sword during the crucial battles of the Camel (656 AD) and Siffin (657) – both of which took place during the First Fitna or Muslim Civil War – to strike down many brave warriors among the ranks of his opponents.

In the year 762, Zulfikar would return once again to the spotlight after being raised by Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn al-Hassan ibn al-Hassan bin Abi Talib – more commonly known by his honorific Muhammad “al-Nafs al-Zakiyya” (“The Pure Soul”) – during the Alid Revolt of 762-763 against the Abbasid Caliphate. The sword was considered a source of inspiration for the Alid fighters, and was a crucial factor in the momentum and traction which the revolt was able to garner in its early stages.

“The Pure Soul” would however be wounded in battle, and subsequently used the sword to settle a debt he owed to a merchant of 400 Dinars, telling him that if he offered it to any Alid fighter, he would redeem his debt.

However, as the thirteenth century scholar Ibn Khallikan narrates in his major works, “Lives of Eminent Men and the Sons of the Epoch”, the merchant would choose to sell the sword to Ja’far bin Sulaiman – who would in turn gift it to the Abbasid caliph Al-Hadi, who stored it in his treasury. Al-Hadi died and was succeeded by his famed brother, Harun al-Rashid, who adorned himself with the sword in front of the people.

Ibn Khallikan relates that Al-Asma’i – a philologist at the court of al-Rashid – witnessed the sword being adorned by the caliph, who also held it in his hands with satisfaction and described it as containing “eighteen vertebrae [fiqara].” The sword would remain a source of boasts and vanity for the Abbasids. Accounts testify that it would continue to be in the possession of the Abbasid caliphs al-Mu’tazz and al-Muhtadi, and would even reportedly be the subject of poems by the ninth century Syrian poet Buhturi, as nineteenth century Egyptian writer and historian Ahmed Taymour notes in his works, “The Prophet’s Traces.”

Moving onto the Ismailis – a major branch of Shia Islam after the dominant Twelvers – where many accounts claim the presence of the sword with some Ismaili Imams – most notably the Fatimid Caliph Al-Mustansir Billah, as Ahmed Taymour notes in his aforementioned works. Accordingly, it is claimed that some merchants in Iraq had purchased the sword from the Abbasids and later sold it to the Fatimid caliphs in Cairo; however, such an account is deemed improbable by simple virtue of the fact that the Abbasid caliphs were highly unlikely to have dispensed with the sword due its political significance – and certainly not to their bitter Fatimid rivals who had repeatedly challenged their rule.

Meanwhile, in his book the “Exhortations and Contemplation of the Recollection of Plans and Monuments,” the 14th and 15th century Egyptian historian, Taqi al-Din al-Maqrizi, reports that Zulfikar was looted alongside other artefacts and munitions preserved in Fatimid vaults during the height of the Al-Mustansirid crisis (1065-1072) – when the Fatimid Caliph Al-Mustansir was unable to provide funds to pay the salaries of the Turkish soldier-corps in the Fatimid army, leading them to storm the caliphal palaces and plunder its treasures. Zulfikar was one of the looted pieces, and has since been lost – with its fate remaining unknown.

Zulfikar would also play a special political role for Twelver Shias as well, with the eighth imam Ali al-Ridha appearing with the sword after being appointed successor to the Abbasid caliph al-Ma’mun in the year 817. Al-Ridha repeatedly took to affirming his belief that the sword was an inheritance of the Prophet that must remain in the hands of the Imam, with its possession a sign of a ‘true Imamate’ – according to tenth century Persian scholar Al-Shaykh al-Saduq in his “Book of Dictations.”

Zulfikar’s remarkably-sustained presence thus continued throughout the years and ages; today, Twelver Shias ultimately believe the sword to be in the company of the occulted (hidden) twelfth Imam, Muhammad ibn al-Hassan al-Askari (al-Mahdi, or the “Guided One”) - who will return with it at the end of time with the mandate of establishing absolute justice on earth.

Between Abu Lu'lu'ah’s dagger and the sword of Zulfikar

For all their variegated contexts and historical detail, most of the above sources have not however provided accurate descriptions of what the actual sword looked like, sufficing instead by affirming the presence of some carvings in it which resembled the bones present in the human spine.

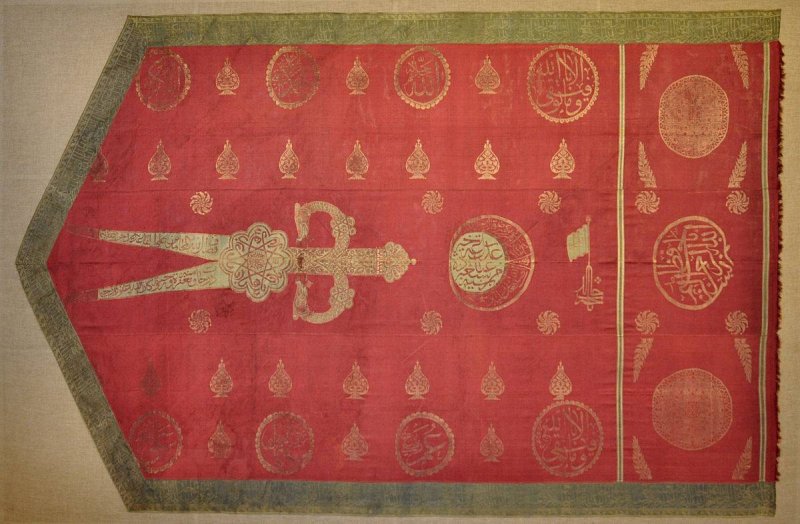

With the arrival of the twelfth century however, new descriptions of Zulfikar would emerge – most notably as ‘two-pronged’ by the likes of Ibn Shahr Ashub, who added that it resembled the staff of the Prophet Moses.

This expression however did not find much resonance within Shia circles, and was not relayed onwards by Shia scholars after Ibn Shahr Ashub nor referenced in their books or works. Yet with the onset of the 17th century, the description would acquire widespread recognition especially with Iranian Shias, as testified by Majlesi’s assertion that it was well-known amongst Shias that the Zulfikar sword was double-pronged.

This major transformation can be justified and explained with the pervasive presence of Abu Lu’lua’h – that is, Piruz Nahavandi: the Persian assassin of the second caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab – in Shia literature during the Persian Safavid dynasty (1501-1736) in particular. Here, it is likely that predominant Shia thought (which had taken an interest in evoking Nahavandi’s story during this period) had taken the image of Nahavandi’s dagger – which most historical sources agree took the form of two blades with the hilt lying in the middle – and projected it onto the sword of Zulfikar; thus, Zulfikar would be depicted as having two prongs or blades in all Shia drawings.

This point of view is supported by the fact that certain Shia narrations – such as those featured in the 11th and 12th century Shia scholar Imad al-Din al-Tabari’s book “Kamel al-Baha’i” – reported that Nahavandi assassinated Umar with a sword forged upon the template of Zulfikar.

Thus, the amalgamation of Nahavandi’s dagger with the sword of Zulfikar took place in the context of the doctrinal Shia imagination which was concerned with highlighting the grievance of the Ahl al-Bayt – the household and lineage of the Prophet – and to shed light on how they sought revenge from their enemies. This mixture (or mix-up) and consequent amalgamation during the Safavid era can perhaps be explained by the observation made by Colin Turner in his book “Shiaisation and Transformation in the Safavid era,” in which he notes that the writings and major works of Mejlesi and other Shia scholars who enjoyed the support of Safavid rulers were often in Farsi – and were, furthermore, written in a fashion acceptable to a large section of Persians – thus facilitating their adoption of the ideas and narrations contained therein.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!