With the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1990, a clear need emerged for the construction of new cultural and political movements that could critically review the experience of the conflict, while questioning the broader issues which constituted the basis of the fighting.

Many such experiments would subsequently emerge – with the most notable perhaps being that undertaken since 2013 by a group of former combatants who spanned Lebanon’s wartime political spectrum. The former fighters would call their gathering the “Fighters for Peace” (FPP), an association which would quickly expand beyond the domain of former fighters to encompass cultural and social figures, experts in psychology and sociology, as well as cinema directors and journalists.

The association aims to disassemble – on all levels – what Lebanon’s age of war produced: proceeding first from the rationale that the end of the war is not brought about by a ceasefire, but rather when a culture of peace is popularised across society.

This entails a rejection of violence as a means of change, protest or resistance to oppression, working instead on crystallising a civil approach that preserves the right to freedom of expression, while searching for commonalities within a wide range of society’s segments.

Ziad Saab: The failure of violence

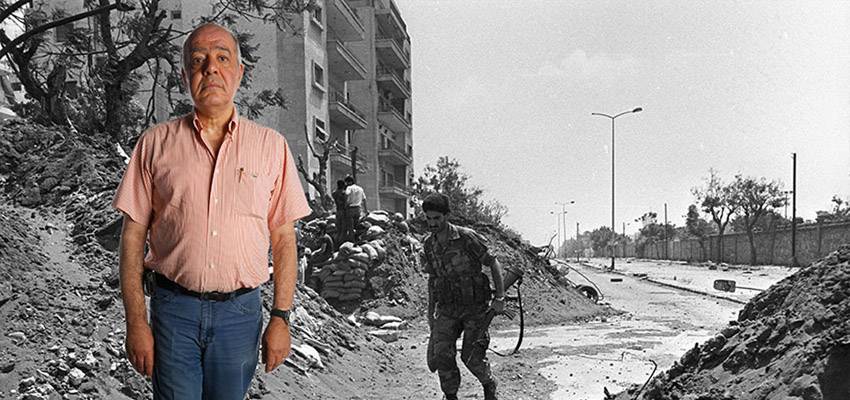

The president of FPP, Ziad Saab, is a senior official at the Ministry of Displaced People in Lebanon. In order to objectively critique the experience of the war, he believes that we must look back to the past with the mindset of the present.

During the war, Saab was a member of the Central Committee of the Lebanese Communist Party and a field commander. Speaking to Raseef22, he says that “the scenes we would see in our vicinity” would lead him, along with his group, to discover that “violence does not lead anywhere, and is not a solution.”

The concept of peacebuilding, Saab says, “is not against rights; that is, peace cannot be built with the abandonment of rights, because then it becomes surrender.”

Saab is forthright in his assessment of the war, even if it undoubtedly negates the struggle of much of his earlier life.

“The experience of violence did not produce anything positive, and the Lebanese experience is very clear in this regard” he says. “Outside of any slogans, we could say that the Lebanese war ended with the destruction of the country without any real advances in any cause. On the contrary, it set loose a regressive trajectory that continues to the present day.”

According to Saab, the “backwardness” that Lebanon lives in today is “nothing more than an extension of the violence established by the war; its climate gave us this governing political class that has inflicted us with this level of public debt. And from this we deduce that the noble causes that our fighters fought for during the war were in vain, and were supplanted by other causes.”

“The trauma of the past and the crisis of the regime”

Saab points to what he describes as the false “polemical relationship” with the past – stating that the main reason he participated in the war was the “historical trauma” which governed the mind.

“When your family tell you of the heroics of your ancestors in the revolution against the French and tell you about the Palestinian cause, [it meant] I did not hesitate to carry a weapon in defence of the Palestinian revolution in 1973 when the very first clashes broke out,” he says.

Saab proceeds to talk of the general crisis of the Lebanese regime, which set up an acute form of centralism that strongly favoured the cities.

“We are among the thousands of families who were displaced during the 1950s from the countryside in search of bread, and herein lies the problem of the regime itself in its centralism that distributed people into the cities and especially Beirut, which allowed for the formation of pockets around Beirut which were later nicknamed ‘the belts of misery,’” he says.

While the concept of achieving change through the barrel of the gun was the prevailing creed at the time, Saab nonetheless refuses to cite this to “justify [my] militarisation and entering the fighting.”

Returning to the present day and his role in the post-war era, Saab says that his ‘Fighters for Peace’ association is not a political party, but a collective of individuals from various political backgrounds, who found a common space where they could work for peacebuilding in an atmosphere of pluralism and diversity.

“Within this diverse context we are carrying out this experiment with the aim of peacebuilding, whereas if we had met before it would have been on the field of battle,” he says.

Fouad Dirani: the fall of illusions

On the other hand, university professor and another employee at the Ministry of Displaced People, Fouad Dirani, says that he rejects any readings of his wartime experience which are based on the dualism of justification and self-reproach -insisting instead on following a critical approach.

Recounting his experience of the war to Raseef22, which entailed him fighting with the Lebanese Communist Action Organisation, Dirani says: “I used to think that I would liberate Palestine in the war and build a more just Lebanon, but our efforts quickly faltered at the start with the assassination of the leader Kamal Jumblatt.”

He adds: “We used to dream of the liberation of Palestine, but then the Israeli incursion of 1978 happened, and another invasion in 1982, and this led to rapid developments which left us with tough questions.”

Dirani subsequently distinguishes between ‘positive’ (active) and ‘negative’ (passive) peace. “A ceasefire does not necessarily equal peace,” he says. “It is not a true and actual peace, but a condition which reflects a negative foundation.”

‘Positive peace’ according to Dirani, on the other hand, recognises the existence of conflicts and disagreements and works on mechanisms which could resolve them. It further acknowledges the rights of others, and is concerned with the provision of bread, housing, freedoms, the right to practice politics, and the right to question those in power and hold them accountable.

Dirani described the power-sharing Taif Agreement that formally ended the Lebanese Civil War as “disappointing.”

“We fought to rebuild the very state, only to find that power was being shared,” he says.

It was from this starting-point of disillusionment that Dirani became acquainted with peacebuilding activists, describing it as an experience that changed his life. Peacebuilding, he says, helped him sort through many issues of crucial importance to him while rescuing him from the disappointments which accompanied the end of the war.

Ultimately, and perhaps most importantly, the experience fully convinced him that approaches which rejected any role for violence in finding solutions were the right ones.

Assaad Chaftari: a spiritual consciousness and discovery of the ‘other’

Conversely, former vice-chief of security and intelligence in the Lebanese Forces (a wartime Lebanese Christian military faction), Assaad Chaftari, does not take us back to his experience fighting in the war, but is instead keen to share the contours of the experience he underwent when he was confronted by the war’s abrupt end.

The end of the war would induce Chaftari to embark upon a serious review of all the concepts and ideas he had previously adopted – consequently giving birth to a ‘spiritual’ experience and his discovery of the ‘other’, as he describes it, and ultimately paving the way for the crystallisation of a new critical, humanitarian and political vision.

Chaftari tells Raseef22: “When I became conscious spiritually and in humanitarian terms and got to know the other, much changed. I realised that despite all the differences and disagreements, we should not have entered a war that killed 200,000 people and caused the disappearance of another 17,000. We have still not emerged today from the ruin we caused our country.”

Chaftari’s analysis of some of the reasons for the outbreak of the war is forthright, notwithstanding his wartime loyalties.

“If the politicians worked before the war, and especially the Christian ones, on giving the necessary rights to Muslims so that they could be on the same level politically, socially and in terms of rights, the war would not have broken out,” he says. “And so I am convinced that justice and equality of opportunity is a basic and permanent prerequisite for peace and tranquillity.”

Chaftari isn’t too optimistic about his country’s current prospects, however.

“On what [basis] are we raising our children today?” he asks. “Have we taken them out of regional, sectarian, and political tribalism? Is there a shared existence after all these years? Is there an insurmountable internal immunity to any external agendas that want to create a conflict inside Lebanon?”

To tackle these issues, Chaftari proposes a permanent body for national reconciliation to work towards achieving genuine national unity, while insisting that the biggest hope for the country lies in working with its youth, who invariably constitute its future.

He says: “If there is a consciousness and critical spirit which can deal with disputes without violence then we can safeguard the future, but unfortunately we did not carry out a national reconciliation or establish its conditions on the basis of truth, justice, accountability, prosecution and compensation.”

Chaftari says that while many Lebanese citizens do not readily believe those who talk of repentance, atonement and peace, convincing them of the importance of these concepts always takes precedence in his work nonetheless, and eventually leads to a greater number of people believing what he has to say.

“It is difficult to convince a society where 250,000 of its members participated in a war that what it did was wrong, and that it should sacrifice for civil peace,” he says. “There is change today but some people are still entrenched behind their convictions, as before.”

Yet Chaftari still believes that there is hope for genuine change.

“Hundreds of civil organisations are working on this subject in one form or another, and this evolution is noticeable when we are on the ground and especially when we participate in debates aimed at school students and the youth,” he says.

Many of Lebanon’s peacebuilding advances have, however, been endangered in recent years by the regional developments and wars which have broken out in Lebanon’s vicinity. These have had negative repercussions for Lebanon’s peacebuilding project, Chaftari says.

“It encourages us to be afraid of one another, and we don’t know whether we could go back to the past at any moment, and so it is necessary to work on activating the culture of peace and fighting the fear of the other,” he says.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!