Umm Walid, Marika Spiridon, Afaf, and Kuchuk Hanem… Names forever engraved in Beirut’s history, where prostitution was commonplace, attracting pleasure seekers in all their different colors. Women occupied a range of professions, from patronesses or madams, to café girls (escorts), mistresses, and artistes, captivating row upon row of men in the soft folds of their skirts.

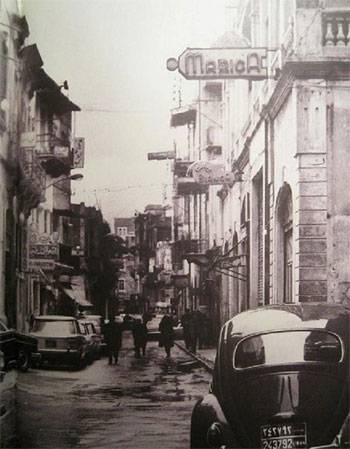

The tales of sex, love, vengeance, and prison continue to be narrated by those who lived during this era of madness, in the infamous Mutanabbi Street. Tales of girls who willingly chose sex work, or were forced into it, while others fell into the traps of madams. Brothels were often guarded by pimps; known as ‘arsat in the local vernacular. The madams would manage the brothels, taking care of the girls, training them, and assigning them house chores during the day and clients at night. The pimp’s job was to lure in clients from bars, and drunkards from the streets, in addition to guarding the brothel and resolving any disputes that erupted between clients over the same girl, or over their turn on the waitlist. Prostitution found its way onto Mutanabbi Street after World War I, before once again diminishing during the civil war that started in 1976. Between the wars, the street was home to countless madams and futuwwat (street bullies).

Theatrical Prostitution and the ‘Bee Dance'

It is undisputed in local lore that Kuchuk Hanem was the inventor of the ‘Bee Dance’, in which a young woman enacts a scenario in which a bee has flown into her clothes, attempting to get rid of it by stripping out of her clothes before she is stung. The scene ends with the performer bare-chested and near-naked. The dance continued as a form of theatrical prostitution for Arabs, beginning with the era of the Muhammad Ali dynasty, and continuing until the appearance of the Lebanese performer Shamlakan. Shamlakan, a Lebanese woman, performed in a moving circus on the borders between Lebanon and Palestine before World War I. After the death of her husband and pimp, she moved to Beirut, where she performed in Mutanabbi Street, which had yet to earn its fabled reputation. Shamlakan was famed for her rendition of the Bee Dance, in which she stripped off all of her clothes, including her undergarments, particularly in exclusive shows in notables' homes. She performed until she was old and lost all her loyal clients. Subsequently, she became impoverished and went hungry, until her death in the Al-Musaytibah district during the locust attack in 1915.

Task Managing in Brothels

After World War I, Lebanese authorities bowed to the pressure of legalizing prostitution. Organized by a Law in 1931, many of the locals did not take well to the legalization, leading the government to claim that restricting prostitution to one street and legalizing it would protect the Lebanese women from the French and Senegalese soldiers. While this claim had no basis, the citizens of Beirut adapted to it, and became convinced that it would protect families’ dignities and traditions. According to the Lebanese Prostitution Law of 1931, brothels were divided into two groups; public brothels, and escort houses. The Law set conditions for sex workers in their movements outside of the brothel, dividing them into groups of workers, café girls, mistresses, and artistes. The legalized public brothels were only permitted to have one entrance, and visitors had to be at least 18 years old. Sex workers had to be older than 25 years old to obtain a full license, while 21-year-old workers were granted a second-degree license.

Virgins were forbidden from stepping inside these public brothels. Escort houses were occupied by café girls, who would meet clients at cafés and agree to a later rendez vous. Meanwhile, private mistresses catered to only one man, and were not permitted to seek out other customers. According to the Law, that one man had to provide for her and fulfil all her financial needs. As for the artistes, they would dance and sing in bars, and only mingled with the clients. They were also known as the fatahat (bottle openers), whose job was to tempt the clients into buying as much alcohol as possible.

The government also set conditions in order to grant licenses to prostitutes, including good health and frequent examinations, depending on their licenses, to ensure that they were free of sexually transmitted diseases, like syphilis. According to the law, the workers were only permitted to leave the house between 9 am and 4 pm, and they were not allowed to leave the house on Sundays or during official holidays. They were also forbidden from wearing a veil. Men were not allowed to own licenses for public brothels; they were reserved exclusively for madams, according to the law. However, two governmental workers were assigned to supervise the madam, to ensure her management skills in the brothel.

Afaf, Nitric Acid, and the Advent of Mutanabbi Street

During the 1940s and 1950s, Lebanese women constituted the overwhelming majority in brothels compared to Greek, Turkish, and Egyptian women. Mutanabbi Street thrived, and became the talk of the town. Every visitor had a story to tell. The street bred more extensions and brothels, where certain madams became increasingly famous and powerful. The most famous madam was Bedour al-Dahwaq.

Al-Dahwaq launched her career in Mutanabbi Street, and when she moved from one brothel to another, she changed her name to Yousra to avoid financial penalties. She had a strong personality, and would not be overpowered by any of the madams of the street. As she grew older, she knew she had to safeguard herself against competition. She almost lost her beauty several times, after being attacked with nitric acid, which causes permanent burns and deformities. She decided to marry one of her clients, named Saied Khaled, who was employed at the investigation bureau in Beirut’s Palace of Justice. He quit his job after marrying her, and granted her a license for her own brothel.

They hired a number of young women, and he personally took over securing the clients and collecting the fees. As for al-Dahwaq, following her promotion from sex worker to madam, she decided to change her name once again to Afaf. One of the stories from within Afaf’s brothel in Mutanabbi Street was about a girl named Rana, who ran away from her family in fear, after she failed her school exams. She was ensnared by Afaf, who first took care of her, only to later sell her virginity to the highest bidder, a governmental employee. Rana became one of Afaf’s girls, changing her name to Lolita. One day, an old neighbor recognized her and told her father. The father went to the brothel and followed Lolita into Afaf’s brothel, where he requested to meet her as a client.

The story goes that when he entered her room and saw her naked, he died of a heart attack. Another popular story was about an Israeli spy in Lebanon, Shula Cohen, who would select the most beautiful girls from Afaf’s house, then train and recruit them to extract information from clients, without Afaf’s knowledge. Cohen covered for Afaf and her brothels several times in Beirut and the Levant. Eventually, the government launched a campaign against brothels in the late 1950s and 1960s, aiming to erode the influence of brothel owners. Afaf’s house was raided, and in 1959, she was tried and sentenced to three years in prison. During her time in prison, she led a protest against the overcrowding of the women’s prison in Baabda. The protest lasted for five days, turning Afaf from a madam into an activist.

Ladies on the Porch

The majority of the women in Mutanabbi Street worked as prostitutes. Those who could not secure a husband or alternative work before they got older and less popular with clients would sit outside on their porches, without any undergarments, and they would try to seduce clients for a small price. The average price for services in one of the Mutanabbi Street brothels ranged from 100 to 200 Lebanese pounds in the 1970s; however, the porch ladies would charge far less, as low as 15 Lebanese pounds for “peep shows”, where they would escort their clients to the entrance of the building to show them underneath their skirts.

Beirut’s Golden Girl: Marika Spiridon

The Greek Marika Spiridon was likely the most renowned prostitute in Beirut. She gained recognition for her beauty, and the longevity of her career on Mutanabbi Street. Spiridon inherited the madam profession from the brothel owner where she worked as an escort, and became a madam in her own right. In a few short years, Spiridon was able to buy the whole building and turned it into a hotel, through which she managed her prostitution business. Although she reigned supreme over her brothel and the whole street, she nonetheless continued to work as a prostitute herself, charging the highest fee on the whole street, and offering her services exclusively to well-to-do clients.

Spiridon had more than 100 young women and 20 employees working in the hotel, and the brothel, which was located on the top floor. Contrary to other Mutanabbi Street madams, Spiridon did enjoy the protection of men of influence, nor did she partner with them in secret. She relied on bribes to manage her affairs, choosing her brothel clients herself. What puzzled many about Spiridon was that she was the most generous donor to the Orthodox Church in Beirut. It was said that she dedicated a huge chandelier inlaid with gold to the church, and would attend Sunday mass at the church without fail, from her first days on Mutanabbi Street, until her death at the age of 100, after the Civil War, in a small house in Furn El Chebbak. Several stories circulated around Spiridon, mostly dramatic and fictional. She was known for her simplicity and precision regarding business matters. Despite the stories, she left her hotel before the ‘Battle of the Hotels’ during the Civil War, and only visited it once before it was demolished during the reconstruction of Downtown Beirut. Nonetheless, she retained her reputation as the most renowned madam of the era.

Umm Walid, A War Heroine

Umm Walid is not her real name; rather, she earned the moniker from a Lebanese film about the start of the Civil War. Some knew her by the name Lama’an, though that is likely not her real name either. She came to Mutanabbi Street after her parents’ death in Palestine. She escaped her grandparent’s house, and later met Hussein al-Kurdi, a young man addicted to betting on horse races by day, and a pimp by night on Mutanabbi Street. Lama’an married him and had three children with him, before he died a few years later, leaving her three large apartments. She was able to live off the rent from these apartments, until one of al-Kurdi’s relatives advised her to take up the signing profession, as she had a rare voice, and so she followed that advice. Lama’an, or Umm Walid, became a performing artist, and it was rumored that the king of a Gulf state had requested her company, showering her with gifts and jewelry.

During one of her parties in Beirut, men competed to drink champagne from her shoes. With the start of the Lebanese Civil War 1975, Umm Walid’s movements became extremely restricted in the deeply divided city. This was compounded by the loss of her voice, from excessive smoking. She lost two sons during the war, one of whom died fighting alongside the battalions, while the other died fighting with a leftist organization. After suffering financially due to the war, she decided to open one of her apartments for prostitution, inviting several of the workers from Mutanabbi Street to work in it. Her brothel was located on the borders of the divided city, and she welcomed clients from the two warring camps. Battlefronts near her brothel would be temporarily allayed when she hosted a party or an occasion.

Umm Walid’s story was later depicted in the film West Beirut by Ziad Doueiri.

It was rumored that Umm Walid’s effect on the battlefronts was devastating to some militia leaders, and that they attacked the area surrounding her house on several occasions, to prevent their men from escaping and spending the night at her brothel.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!