Hussein Beydoun was only able to celebrate getting married to his beloved last month. The party had been postponed for nearly an entire year, after it was scheduled to take place during the summer of 2020. On August 4, 2020, Hussein and his bride were about to finish preparing their marital home on Mar Mikhael Street, just opposite the Port of Beirut. He remembers that a strong force lifted him into the air and then he fell to the ground. It was a blurry moment when he woke up before he could re-orient himself, his body full of shrapnel, in the midst of a sea of rubble.

Many say that they are survivors, but they are acutely aware of the fact that they carry the fragments of that explosion in their souls, even if their bodies had escaped it. To this very day, what happened has left a scorching mark on the hearts of people, young and old. A year later, people are still unable to comprehend what happened and are still living in shock.

A year passed before Hussein and his beloved were able to celebrate their love, but time does not go back, even if it seems that things have finally gotten back on track. For him, it was no longer the same Beirut he knew — the one he had wanted to settle in, “The city was getting uglier due to what the regime was doing to it and its public property. But after the explosion, and with the economic crisis, looking at its streets and its people makes me feel as if something has stabbed me in the back.”

The city itself isn’t the only thing that has become strange to its inhabitants. The daily details that make up their lives have also become alien, “I wake up sad every day. Beirut has overwhelmed me, defeated me. The city pains me. I am still terrified of loud or sudden noises and have nightmares every day,” Hussein says.

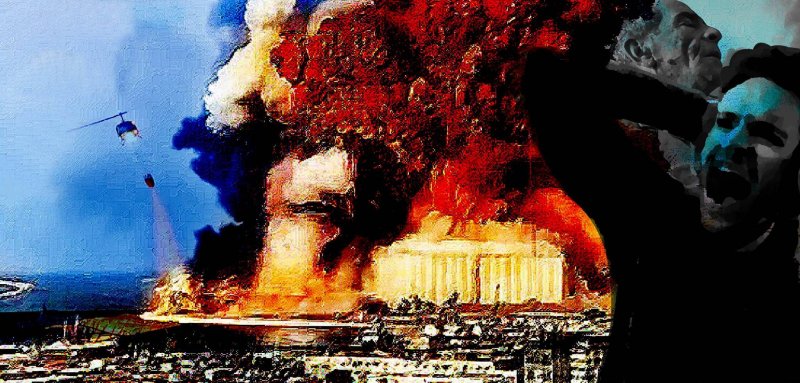

The Beirut port explosion was classified as one of the world’s biggest and most violent non-nuclear explosions in history. It had taken place as a direct result of storing 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate in a warehouse at the Port of Beirut for more than six years without taking the necessary safety precautions.

The blast killed more than 217 people and injured about 7,000 others. In addition, around 800 people became permanently disabled as a result of the explosion, according to Sylvana Lakkis, president of the Lebanese Physical Handicapped Union (LPHU).

Also, about 70,000 workers lost their jobs. In terms of material damage, the explosion damaged around 200,000 housing units, and displaced about 300,000 people.

Just like that, in an instant, thousands of residents of the Lebanese capital — irrespective of their circumstances or even their privileges — found themselves pushed to the margins, and stripped of the minimum standards of safety.

Escaping Punishment

So far, those responsible for the explosion have succeeded in evading punishment. This issue is not a new one. It is a policy that has been established and adopted by the Lebanese authority for decades. The horror and sheer magnitude of the blast led to the belief that punishment was inevitable this time, but no one has yet been brought to justice, despite the lead judicial investigator in charge of this case, judge Tarek Bitar, having summoned senior officials in connection with the case.

Bitar is still waiting on security chiefs, former ministers, and representatives suspected of being responsible for the crime, to present themselves before him. However, up to this moment, no grants or permissions have been granted to prosecute the security figures, and the political immunity of the accused representatives has not been lifted. Immunity — whether parliamentary, partisan or sectarian in nature — has often raised officials above the law and kept them out of the reach of punishment and prosecution.

Immunities such as these make up the most prominent obstacle that is hindering investigations into the port explosion case.

“Justice for the Victims, Revenge Against the System”

In the home of the victim Ghassan Hasrouti, their mourning continues. His family is trying to deal with the pain of his passing while they wait for justice to be served. His children try to console themselves with the emphasis on their pursuit of justice and fulfilling their father’s desires to carry on as well as realize their potential.

His son Elie, a young engineer, says that before the blast he did not expect the family to pay any of its own members as a price for the country’s corruption. Hasrouti, the 59-year-old father, had been employed for nearly four decades in the well-known grain silos building in the port. He had managed to escape death during the Civil War and would sometimes take refuge in the corridors of the silos building. However, he ended up dead even though it was during times of peace in his age-old shelter while on the job.

From the very beginning, his family raised its voice in demand for the search for Ghassan, and criticized the negligence and underperformance of those concerned. But the family was left alone to spend 14 days waiting in pain for them to determine his fate.

After hearing the news, Elie went looking for his father, full of hope in finding him. Despite the sheer magnitude of the explosion, he kept hoping that his father had taken refuge in the corridors of the grain silos building that he had committed to memory long ago. This eagerness was met with coldness by those concerned, who at the time confirmed that they were waiting for outside expertise to arrive and conduct the search more thoroughly.

In this blast, I see how the authorities come up with new ways to kill us every day, and if I cannot imagine a more horrific crime yet, I don’t expect the crimes of the regime to stop.

The family kept trying to pressure them to speed up the search operations, with the son trying to communicate with those in charge in order to pressure them and push them to search the building, but they kept hearing different excuses. Two whole weeks after the explosion, the body of Ghassan Hasrouti was identified.

Following the tragedy, Elie became more aware of the reality surrounding the political parties in the country. He tells Raseef22, “I found out that each party presents people as victims and refuses to sacrifice itself, but rather sees that it has accomplished what it must do.”

Tatiana, the youngest daughter of Ghassan Hasrouti, considers herself less fortunate than her siblings, as she, due to her age, had spent less time with her father, “I wanted to share my graduation and my marriage with him and for my children to know him. I am sad that my father will not live through these moments with me,” she tells Raseef22.

Like her brother, Tatiana is armed with “faith” to overcome the pain of losing her father, for whom she had spent 14 days praying for his rescue. She faithfully accepts his departure, and strives for her tragedy to never be repeated with others.

Marginalizing the Image

Hussein Beydoun considers himself a victim of the regime. When he describes his suffering — which began from the moment he fell to the ground when the explosion took place — understanding the meaning of being a victim of a crime the size of the Beirut Port explosion becomes much more than just solely falling under the statistics and official numbers. Rather, it shows the extent of the harm and how much it goes beyond the surface.

Beydoun works as a photojournalist for the New Arab (or Al-Araby Al-Jadeed) newspaper. The 30-year-old has become a familiar face to protesters on the streets of Beirut over the past decade. Those who know Hussein are well aware of his stance when it comes to the regime, as he is quite opposed to it in its entirety.

Beydoun is famous for taking photos of politicians during moments that were supposed to be serious, but he has instead been able to capture the comedic side of them, giving these instances a new perspective that some may call political.

On the 4th of August, Baydoun felt a force that lifted him off the ground and then threw him back down. He woke up surrounded by total devastation, his body riddled with shrapnel. In a completely spontaneous reaction, he picked up the camera, took to the streets, and began documenting what he saw around him. He was only able to document part of what had happened, but his memory recorded even harsher details.

Beydoun was taking pictures while blood was dripping from his hand, head, and stomach. He was mutually filming the tragedy and looking for a hospital to bandage his wounds at the same time. One minute he would be trying to comprehend the enormity of the explosion that happened, while another minute he would try to document it. There were moments when he would just stand in place for minutes on end, asking for a cigarette from people he did not know.

“I kept asking myself: Is this real?” he tells Raseef22. He was able to successfully take pictures, but his wounds remained untreated. He waited until the next day, following a long search, to find a hospital that would accommodate him. He was able to eventually get the shrapnel extracted from his hand, but without the use of the necessary anesthesia and equipment.

To this day, Beydoun is still documenting “August 4”. He sees the failure to hold anyone accountable as “physical evidence of the state’s impunity and tyranny, and an affirmation of the inseparability of corruption from the survival of this ruling class that won’t care whatever happens.” Just like losing the days when he would wake up optimistic, Hussein has also lost his final streak of faith in Lebanon and the possibilities of political change.

He says, “What increases my feeling of pain and sorrow is not that I almost died, but that people I know and meet every day in my workplace and residence have been subjected to the blast.”

“I cannot accept seeing any political or security official. When I see any of these people, I feel sick and my stomach hurts.”

For Hussein, this feeling of distress is exacerbated by the growing lack of hope for any sort of serious accountability, saying he is not waiting for a court ruling, “I know that no one will be held accountable or punished, and if those who blew us up were brought in front of me and executed, I will demand for more revenge. I want them to suffer.” He continues, “In this blast, I see how the authorities come up with new ways to kill us every day, and if I cannot imagine a more horrific crime yet, I don’t expect the crimes of the regime to stop.”

The explosion has imposed itself on Hussein’s views and now he sees the profession of photography very differently. “I am one of those who believe that the mission of a photograph is to address an issue, show the truth, and push people to rise up or take a stand, but after the explosion I felt that my camera and I were useless. No photo or cause engaged or concerned me anymore. I felt disgusted with the camera and photography, and up till now, I have not been able to restore my passion for photography as a result of the trauma. Maybe I did not only lose my passion for photography but also my passion for everything,” he says.

Being a photojournalist makes his experience more complicated on a daily basis, “I cannot accept seeing any political or security official. When I see any of these people, I feel sick and my stomach hurts. The first time I was asked at the newspaper I work in to go to the residence of an official after the explosion, I suffered from cramps in my stomach. Today, I avoid going to any official headquarters or events held by any of the political parties.”

Hussein talks about “the absence of the state after the explosion”. He remembers how “people were left to their fate,” and says, “We had to live through moments of searching for the missing and the bodies ourselves.”

The same sentiments were expressed by the Hasrouti family and the families of other victims over official authorities failing to do their part in searching for their loved ones. In addition, the volunteers were left in the early days to carry out relief work and remove the rubble by themselves, whereas the participation of the relevant authorities seemed meagre at best, as it was mostly limited to the deployment of security forces to control the streets.

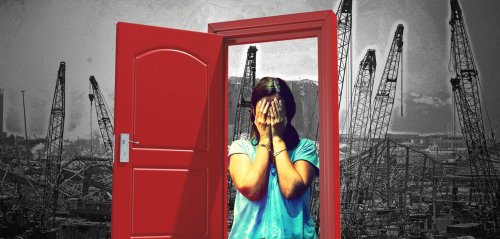

Nour, too, feels alienated in the city after the explosion left her homeless. This was not the first incident of violence that caused her to become displaced. The 35-year-old, who is afraid of disclosing her full identity, is a Palestinian refugee who fled Syria for Lebanon in 2015 and began working in aid programs for children in Palestinian camps. When the explosion took place, she was in a tailor’s shop in the Furn El Chebbak area, thinking about the dress she was going to wear to an event she was invited to. “When I heard the explosion, I was terrified,” she tells Raseef22, “I thought it was ISIS.”

Before leaving her home in Syria, the young woman used to suffer from the constant sounds of explosions, which usually preceded the “storming of some headquarters or stronghold”. This fear is etched like a scar into her memory. Today, on top of all this, the sound of the Beirut blast also echoes in her head. “I immediately went to my house, and I found broken glass everywhere, so I left for a friend’s house outside Beirut, and I stayed there for days until I was able to begin removing the broken glass in my house,” she recounts.

Unlike Hussein, Nour was not injured during the explosion, but up until this day she avoids heading to the area surrounding the port of Beirut. “I did not see those areas and I do not want to see them. I cannot see the destruction that was inflicted on it. Even if people go back to staying up late in their bars, the traces of the crime are still visible. I do not take the road that runs parallel to the harbor. There I feel like I’m in a horror movie,” she says.

Neglecting the Wounded

As a result of the explosion, 800 more people now belong to the disabled and special needs category, the same category that the government continues to deprive of their most basic rights to live in dignity. As was expected of the corrupt state, under the current political authority and regime, it had not secured any sustainable support for them as individuals with special needs and disabilities.

As for those wounded in the explosion — other than the fact that they are deprived of their right to compensation, reparation, and seeing justice served — no one is paying for the expenses of those who still need to continue their treatment.

Currently, this event is not from the past, because most people are living and experiencing it as if it happened today because we never understood what happened and who is responsible. This leaves everyone just waiting for answers to see how they will continue their lives

The costs of treating the wounded when they were admitted to the hospital immediately after the explosion were covered. But after that, the authorities left the injured who came back to have operations and those whose cases required treatments for a long time to deal with the costs themselves and bear the difference that insurance would not pay, if there was any.

On her 28th birthday, which coincides with the date of the blast, Hanan Bazaza will mark the first anniversary of the death of her sister Malak. On the day the explosion took place, Hanan was with members of her family at the Loris restaurant in Gemmayzeh. There was a very sudden and loud sound. Her sister’s husband was killed instantly while her sister fought death in front of her for a long time. It was two hours before she finally took her last breath. As for Hanan, she was injured and broke her leg when a wall fell on her.

Hanan with her family at the restaurant moments before the blast

Hanan tells Raseef22, “I underwent an operation, but I fell victim to a medical error. I had an operation on my leg, and instead of getting better like the doctor promised I would, I got worse. I then consulted three other doctors who all confirmed to me that there was a medical error that required a second operation. I had to undergo another operation. The Ministry of Health refused to cover the costs of the second operation, and informed us that it doesn’t cover any costs a month after the explosion. I was forced to pay the difference in the price since it was also not covered by insurance. This is unfair, but I realize that there is no state (proper government) in Lebanon.”

Even today, a year after the explosion, the young woman is still unable to walk normally, and needs more treatment.

As for the emotional distress, Hanan recounts how her pain continues to this day as a result of watching her sister die in front of her. She says, “Psychologically, during the initial period, things were easier. These days, I have begun to feel the shock and fully realize what happened. Things became even more difficult.”

The young woman hates politics, but she asserts that the crime of the Beirut blast and its aftermath is a “political issue”. She accuses “the state, the parties and the judges” of causing the explosion, “They are all responsible, and we have questions that we do not have the answers to.” She adds, “I wish I knew the truth, it would have made me feel better. I would have known who killed my sister, orphaned her two children, and hurt me. I wish I knew the criminals by name.”

In addition to all the harm inflicted on her, the blast changed Hanan’s plans and governed her decisions. “A life that I did not choose has been imposed on me. My dreams fell apart and were destroyed. I used to dream of completing my studies, working, and traveling, but my life was turned upside down. I could neither complete my studies nor work. I stayed home for seven months during which I had two operations. Also, new responsibilities were imposed on me. My sister left two children who now live with us in the family home. My parents care for them, but I now have a responsibility towards them,” she says.

Time for Vengeance

For hundreds like Hanan, the blast robbed them of their right to lead a normal life and prevented them from choosing the life that they had wanted.

Before the explosion, Ibrahim Hoteit, 53, was working in advertising. But he has stopped working ever since the blast happened and his brother Tharwat was killed. Since then, he has devoted himself to demanding justice. As head of the Port Blast Martyrs’ Families Committee, he has been pressing for an investigation into the crime and calling for the rights of the wounded and the victims’ families.

These rights, which would seem self-evident in a country that respects human rights, can only be reached through struggle in a country like Lebanon.

Following many efforts and movements, in October 2020, a law was passed that equates the victims of the port explosion to martyrs in the Lebanese army, and grants the relatives of those who lost their family’s breadwinner the salary of a soldier.

Hoteit points out that the state has so far refused to grant any salary or compensation to the wounded who now have disabilities that prevent them from returning to their jobs. Whereas the families of the victims did not begin receiving the salaries and compensation approved by the law until several months after the aforementioned law had been passed.

The moment Ibrahim learned of an explosion in the port of Beirut, he went to the location to look for his brother Tharwat, who was a member of the Lebanese Civil Defense. But the search was not easy, as was communicating with the relevant authorities. At the gates of the port, which he was denied entry to, he met the families of the victims.

“Some were looking for a father, others were looking for a brother, a husband, a son. Right then and there, we exchanged our phone numbers in order to inform each other of any new information that we might come across. It took me 11 days to be able to find my brother’s body. During this time the relationship developed between us as the families of victims. About 40 days after the blast, we held a meeting together and agreed to make our first move at Gate No. 3 in front of the port, in symbolism of the exact location that our martyrs were brought out from,” he tells Raseef22.

This is how the families of the victims met and the committee came to be. Hoteit continues, “On that day, we announced ourselves. We were few in number but then began to increase, and we established the Beirut Port Blast Martyrs’ Families Committee. We united under the same title, demanding to know the truth and the fact that this corrupt system in its entirety is responsible for killing our loved one. For us, everyone is accused until proven innocent.”

Injustice is a Reflection of Criminality

The passage of time without the start of any process of accountability has exacerbated the psychological damage and pain for the wounded and the families of the victims.

Dr. Rabih El Chammay, head of the National Mental Health Program at the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, confirms that the process of healing from the psychological repercussions of the explosion begins when the truth is revealed and justice is served, and that this helps people to ease their wounds so that they gradually heal and the pain they feel ends.

He adds to Raseef22, “Of course, there should be interventions for emotional and psychological support to alleviate the pain of these people, but it is very important not to turn a societal, humanitarian, and human rights issue into a mere medical or psychological issue.”

Speaking on the relation between justice and mental health, El Chammay explains, “We do not know what happened, and this leaves a feeling of rage and helplessness among those who have lost a loved one or a part of their body. In order for people to be able to comprehend the repercussions of this event, piece themselves back together, accept the loss, begin the phase of mourning, and carry on with their lives, there must be a sort of closure for this event so that it becomes a part of the past. Currently, this event is not from the past, because the majority of people are living and experiencing it as if it happened today because we never understood what happened and who is responsible. This puts everyone in a state just waiting for answers to see how they will carry on with their lives.”

El Chammay’s analysis shows how the insistence on evading justice serves as an intentional increase in the damage on the victims of the explosion, regardless of the various forms of harm that had been inflicted on them.

The ongoing economic crisis further increases difficulties in accessing psychiatric treatment, which further marginalizes this category left by the explosion.

The Crime’s Effects on the Face of a Young Woman

On the face of Bushra Sa’ab, a young woman in her thirties, the blast left permanent marks. It scarred her, changed the features of her face, and made her vulnerable to discrimination and marginalization. “I now look strange,” she tells Raseef22.

At the time of the explosion, the secondary education teacher was in her home in the Ashrafieh area. Next thing he knows, she comes to at the hospital and does not remember anything else of the entire ordeal.

Bushra believes that her reaction is different from that of the others who were wounded. She says, “From the start, from the first few weeks that followed my injury and as a result of my being busy with preparing for the operations that I had to undergo and then preparing for travel, I moved around a lot in the streets. Being so busy and all this running around helped me wake up quickly from the shock, I realized what had happened, and I went out to the street in defiance and in spite of it.”

As she walked through the streets, she was confused by the looks people were giving her. “It seemed as if they had never seen any of those who were injured, even though the explosion had left many wounded in its wake,” she says.

Not long after her injury, the young woman was subjected to a hurtful situation while she was in a store, where she suddenly came under suspicion and her belongings were searched without having done anything wrong. Sa’ab sees that such things happen because of the way people look at her now, which differed after her face was disfigured from the injury, “When you see a strange appearance, the person is then suspected more, and it is thought that he has bad intentions or that he might steal.”

Despite the discrimination she was subjected to, Bushra considers that what happened to her face is a tiny detail in the face of what she feared had happened the moment she woke up in the hospital and read the word “BRAIN” written on her hand. “That day, I was afraid that I had lost some of my mental abilities or was suffering from a loss of brain function,” she says.

Bushra Sa’ab, while receiving treatment at the hospital

Sa’ab also suffered from problems in her vision as a result of an eye injury. She says, according to what she is experiencing, that “I understand the suffering of people with visual disabilities, and I noticed that the country’s administrations lack any sort of set up that could help this group or category, and while looking for help everywhere, it was difficult for me to justify my inability to see clearly as a result of the explosion.”

Today, Bushra still suffers from problems in her breathing, and the effects of the explosion remained on her face and changed her features forever. “I have one eye that looks different from the other. Whoever sees me will just think I look weird and won’t know that I was injured by the explosion.”

In addition to all that she has gone through, the young woman, as well as many of the wounded, had to bear the financial burdens necessary to continue her treatment. To boot, the costs had also greatly increased due to the financial crisis and the collapse of the exchange rate of the Lebanese pound (LL).

Bushra avoids watching the news, “because I know things are headed in a bad direction and I have no hope left. I want those involved to be tried and executed, but I know that won’t happen now. Right now I am trying not to let it affect my future. But in the long run I have a personal vendetta that I will achieve, even if it took a million years. I will take my right from them and the rights of others. Me and them, we’ll meet again one day and time will tell.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!