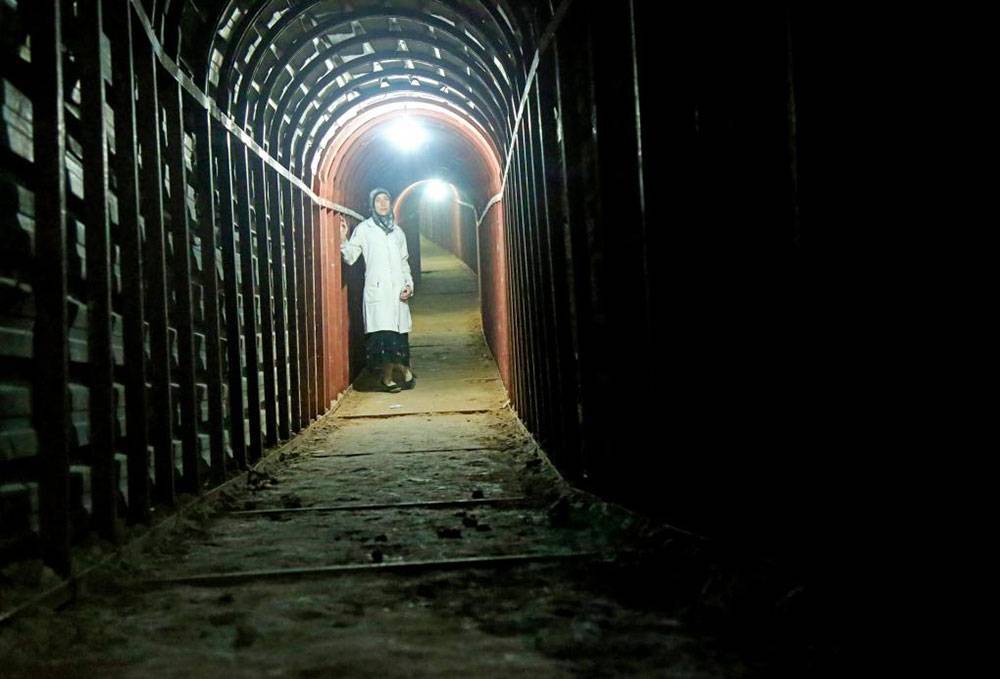

A field hospital run by a female doctor in her late twenties, located underground in a completely besieged area, considered one of the most dangerous places in the world. The residents of the area are bombed around the clock with the fiercest internationally-prohibited weapons. Massacres in the hospital's vicinity occur almost daily. Yet in spite of the small number of medical cadres and the scarcity of available medical materials, the hospital remained a refuge providing medical care until the last minute.

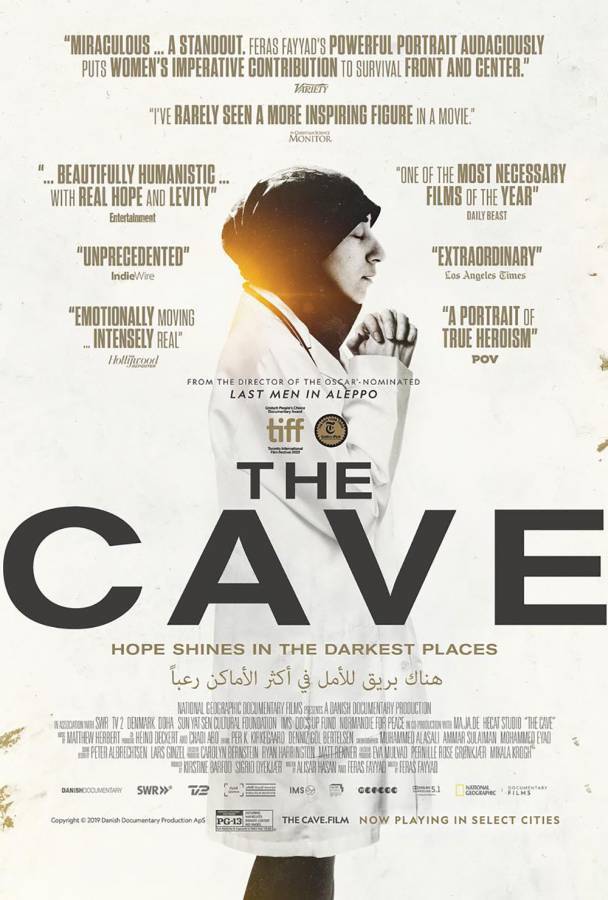

This is a summary of the story of Al-Kahf (Arabic for "The Cave") Hospital, which was administered by Doctor Amani Ballour in Eastern Ghouta in rural Damascus (Rif Dimashq) .The story might not have been believable had it not been for the film directed by Feras Fayyad, written by Alisar Hasan, and named after the hospital: The Cave.

The film has recently been nominated for an Oscar by the Academy Awards for the category of best documentary film – portraying intense scenes, detailing the lives of hospital workers, documenting the fullness of the place with the noise of aircraft bombing and the screaming of the wounded – sometimes capturing the eyes looking up at the sky as they watch warplanes flying over the vicinity – focusing in many of its scenes on the operations room steeped in both pain and hope.

Yet these scenes, with all the contradictions they entailed, had only one leader: the protagonist of the film and the hero of the hospital staff: hospital director Amani Ballour, who did not only challenge the Syrian regime but also defied custom and tradition.

We were convinced that we were going to die

In her interview with Raseef22, Doctor Amani Ballour reveals how “The Cave”, filmed in 2016, came about. According to Ballour, the film's director Feras Fayyad suggested filming a documentary film about the hospital: "the proposal came three years after Ghouta suffered from siege and bombing, and the international community was indifferent to what was happening to us" Ballour said.

As for the most painful stories that live in the memory of the young doctor, it is about a 7 year old, whose parents brought him to hospital with part of his brain coming out of his head with heavy bleeding from his ears, the result of bombing. #TheCave

She continued: “Initially, I refused to participate in the film, fearing the dangerous security situation, and in order not to disturb the patients with the camera. But after discussions with Firas and the young cameramen, I realized the importance of the idea and agreed to it, especially since we were all convinced that we would die in Ghouta – thus this film could be a final document which spoke in our name."

While the film was being made, a lot of massacres took place and many innocent people died, Ballour says: "As far as I was concerned, I was doing my usual job whose difficulties I had become accustomed to – but the film crew was shocked, for it's not easy to film in a place filled with corpses."

The Oscar is not the film’s goal

The young doctor was not expecting the film to be nominated for an Oscar, and indeed, was unable to visualize the work in its final form. The only wish she had was that the film would contribute to conveying the voice of Ghouta to the world; nonetheless, she confirms that the film’s nomination for an Academy Award gave her a sense of pride and happiness, “because a larger number of people will see what happened in Ghouta.”

In addition to the Oscar nomination, Amani Ballour was personally awarded the Raoul Wallenberg Award in recognition of "her courage, boldness and determination to save the lives of hundreds of people during the Syrian war," according to the statement of the Council of Europe, which granted her the award on January 15, 2020.

Yet Ballour reaffirms, that the award (as well as the Oscar nomination) was not “the Goal of the Film, but rather a tool to achieve its goal."

She continues: "What I really hope is that the film will be a pressure tool on public opinion and the international community to mobilize and save civilians, and to help move the humanitarian and human rights organizations to provide assistance to millions of civilians." She added that "most Syrians feel hopeless and have lost hope in the international community, which is able to assist Syrians but does not have the willingness to do so”.

Ballour believes that the Syrian regime succeeded in distorting many facts and in obfuscating many massacres, such as the massacre perpetuated in the 1980s in Hama for example, and it was possible for the regime to succeed in doing the same thing in Ghouta. Thus, Ballour states: "Therefore I see that The Cave as a living testimony that genuinely narrates what transpired without any addition or omission”.

"Many disapproved of me running the hospital"

In addition to the film showcasing the suffering of civilians and the medical team, it deals with the issue of the attempts to marginalize and neglecting the role of women, by showing some drawings of graffiti hostile to the leadership of women, as well as displaying the attitudes of many men who reject their work.

But the main stars of the film are hospital director Amani Ballour, doctor Alaa and nurse Mona. Here lies the paradox that Fayyad's camera expertly captured: stressing the importance of the role that Syrian women have played and still are, despite some attempts to strip them of their rights.

Nominated for an Oscar, #TheCave’s Dr Amani Ballour said: We were all convinced we would die in Ghouta – this film could be a final document which conveyed the voice of Ghouta and Syrians. A documentary not to be missed

"The cave proved the vital role and importance of Syrian women on the ground," says Ballour, adding that "the film did not achieve its goal of changing the reality of women, because change needs an accumulation of effort and time, and these efforts must come from women themselves." Nonetheless, she considers the film a good step on the path to change.

Many opposed the idea of Ballour being the manager of the hospital that she volunteered to work in since the end of 2012, after graduating from the Faculty of Human Medicine at Damascus University, based on their refusal for "a woman to be a hospital director”; yet Ballour succeeded in administering the hospital over two years – thus in her opinion "confirming that we are able to change, but we have a long way to go."

Indeed, Ballour does not shy away from displaying her happiness when some men are forced to retract their previous positions: "I felt like I could make a hole, even if a very small one, in the wall of patriarchal culture," she says.

Thousands of corpses and much helplessness

The most difficult moment that Dr. Ballour encountered during her management of the hospital was when the chemical massacre August 21, 2013 chemical massacre in Eastern Ghouta took place. She recalls: “The moments and details of the massacre cannot be erased from my memory. Hundreds of bodies piled up in the hospital. Hundreds of children dying before our eyes. We could not do anything to help them. The hospital was still in its beginnings and there were few cadres, and we were not prepared to receive these numbers of victims. "

As for the most painful stories that live in the memory of the young doctor, it is about a seven-year-old child, whose parents brought him to hospital with part of his brain coming out of his head with heavy bleeding from his ears as a result of the bombing.

Ballour proceeds to narrate that the child had no chance to survive, but that he remained alive for long hours, and his parents were waiting for his death with a broken heart: "after his suffering lasted for several hours," she says, "his mother asked me to give him an injection of merciful death [euthanasia]. She told me: 'Can you give him something to kill him?' The request shocked me and was very very painful, especially that the mother was devastated, but I am a doctor whose mission is to help the souls and not end the lives of anybody whatever the circumstances. I did not find an answer to the mother's request. All I could do is leave and let her bid farewell to her son. I think that day was one of the days I cried the most in my life.”

All the days are sad in Ghouta

In "The Cave", Doctor Selim adopts classical music as a means of therapy that accompanies him during his surgical operations. Even when one of the wounded was screaming in pain, Selim tried to persuade the patient to listen to the music, in an attempt to alleviate his agony – as if he wanted to conceal the ugly reality with melodies that may carry a glimmer of peace.

Doctor Selim was not the only one refusing to surrender to the sounds of the bombing of Russian warplanes, but also Mona, a nurse, who was in charge of logistical matters in the hospital. It was noticeable that in all of her scenes, a smile never departed her face – while doctor Alaa is shown in more than one scene as keenly trying to drive Dr. Amani towards hope and optimism.

#TheCave is a living testimony that genuinely narrates what transpired in Damascus’ Ghouta without any addition or omission, Dr Amani Ballour agreed to it so that the world sees what the Government did to the people

"Every day was a sad day in Ghouta, but despite the catastrophic situation we were trying to create a space of joy that could remind us that we were still able to feel happiness," says Ballour.

Today, Amani resides in Turkey, where she was forced to migrate following the displacement of the people of Eastern Ghouta in the regime's infamous green buses. She says: "Despite all the scenes and massacres, I felt content internally because I contributed as much as I could to alleviate the suffering of some of the victims, but today, after we were displaced from Ghouta, I feel more responsible because I am outside Syria, and at the same time I have a duty to continue to support and help my family on the inside [Syria]. I think that most Syrians share with me the same feeling, and there remains hope to return to our homeland after the criminal's departure."

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!