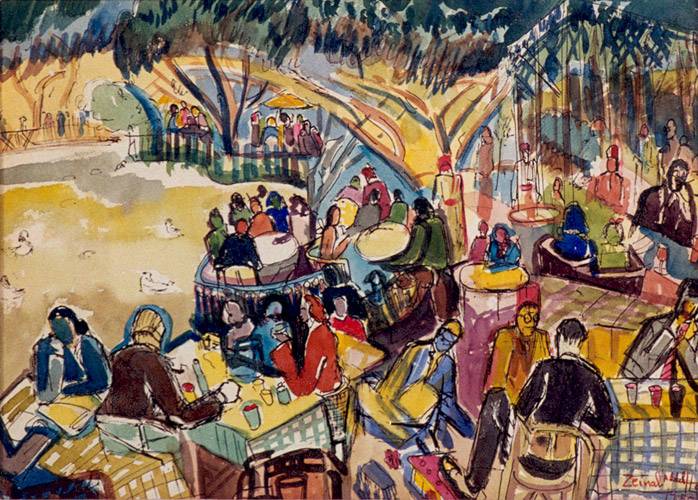

In the luminous streets of Quartier Populaire (1956), lemon yellow cable cars stretch alongside bright red and maroon strips of pavement, sharing their path with horse-drawn and hand-wheeled wooden carts painted in pale blue and lime green. The hyper-saturated reds, sunny yellows, and vibrant green hues of the road and buildings are grounded by wide diagonal stripes of dark brown oil — the street itself— as well as the black khimars of figures within the composition. Quartier Populaire is rich, alive, textured, and tangible. Even now, over six decades after the Egyptian artist Zeinab Abd al-Hamid painted it, we can smell the food piled high in carts and baskets, feel the sun-warmed ground beneath women sitting together on the sidewalk. The expressive style of Abd al-Hamid’s brush, both gestural in its rhythm and precise in its boundaries, invokes the cacophonous clanging of trolley bells overlapping with hooves on cobblestone, combined with the voices of dozens of people pouring into and out of view. Abd al-Hamid’s work, as in so many of her paintings, seems to breathe life into landscape, all from the perspective of a bird’s-eye view. From her perch, we witness modern Egypt in motion — meeting the machines of the 20th century in kaleidoscopic color.

The paintings of Abd al-Hamid (1919-2002) are radiant, expressive, intricate, and dynamic. From her linear watercolors to savory oils, Abd al-Hamid’s depictions of city streets gleam with warmth and light. The art critic Mahmoud Bokeshish described her work as shining, spontaneous, and sophisticated. In the words of Emile Azar, “Her paintings are characterized by strong moving lines filled with vitality and violence,” a reflection on the subtly subversive role of Abd al-Hamid’s career within Egyptian Modernism. Yet the acclaimed painter is largely absent from any English archive. Despite the success of her career throughout Egypt, much of Europe, and the United States, the pervasive private collection of her work makes it frustratingly difficult to find her paintings with accurate names and dates, much less uncover her intent. Sadiyya Haartman once asked: “Is it possible to extend or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive?” She resigned herself, as I have, to try. In the tradition of artistic analysis, we begin with what we can see.

Locating works like Quartier Populaire among one particular category of art history is difficult, especially given the complicated global experiences of Zeinab Abd al-Hamid. In the context of Egyptian art movements, it is useful to take a step back to find her place within the national story. Liliane Karnouk provides a helpful synthesis in her book Modern Egyptian Art, beginning with The First Generation, defined as the inaugural graduates of Prince Yusuf Kamal’s first ever Egyptian art school in 1908. Notable artists of this generation included Mahmud Mukhtar, Raghib Ayyad, and Yusuf Kamil. Their work was largely inspired by re-defining Egyptian culture during and after British occupation, rejecting Western aesthetic values. Neo-Pharaonism and La Chimere, the reclamation of Egyptian folk art, were central themes of this era. Karnouk continues chronologically with her description of The Second Generation, placed between 1935 and 1945 and grappling with a world at war.

This era encompasses the rise of Egyptian Surrealist group Art and Liberty, founded by Georges Henein in anti-fascist solidarity with the work of Frenchman André Breton, Mexican Diego Rivera, and Russian Leon Trotsky. This era’s emphasis on the global unification of artists was eschewed by Karnouk’s Third Generation, which emerged just as Abd al-Hamid graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Alexandria. Characterized by The Group of Contemporary Art and the seminal painting The Theatre of Life (1948) by Abd al-Hadi al-Jazzar, this time period immediately preceding the revolution of 1952 was marked by a return to folk-realism. Karnouk explains that, “Unlike the previous generation, which had taken a militantly partisan stand on the political crisis, this new generation withdrew from the ideological debate . . . turned away from the cosmopolitan art now favoured by the ruling class, and concentrated on creating a new rapprochement between the people and the educated classes.” The brightly colored, flattened, and figurative paintings of al-Jazzar and Hamed Nada demonstrate a similar technical approach to that of Abd al-Hamid, as does their shared portrayal of ordinary Egyptian citizens, not the exceptionally wealthy or powerful. This subtly political diagnosis was replicated in the 2018 biography Painter Zainab Abdel Hamid, where editor Izz al-Din Najib also argues that her work most approximately fit into the Third Generation, with artists using less explicit propaganda. In his foreword al-Din Najib summarizes that: “Their aim was to combine in their works and artistic entities between modernity, originality and patriotism in search of identity unique to modern Egyptian art. It was also an effort to link their creative movement with waves of progress and freedom and the general state of revolutionary labor.” Al-Din Najib illustrates Abd al-Hamid’s participation in a generation leaning on the authenticity of self-expression as well as a renewed openness to the integration of Western techniques with a nationalized Egyptian taste.

Chantier Occupe was sold by Christie’s in 2018

Throughout her career, Abd al-Hamid reflected Egyptian Modernism through a global lens. After receiving her undergraduate degree in 1945, she married the painter Ezzedin Hamouda. Abd al-Hamid co-founded the Modern Arts Group in 1947 before moving with her husband to Madrid to attend graduate school, finishing her professorship in 1952 with the Mediterranean between her and the revolution. According to Khala Hamouda, the couple’s daughter, her father Ezzedin was on government scholarship while studying in Madrid, and in 1964 he was appointed by the Egyptian government as cultural counselor to the embassy in Mexico City. This state-sponsorship was a product of President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s emphasis on the international elevation of Egyptian art, also reflected in his creation of the Alexandria Biennale in 1955 and his incentives for artistic representation of the Nationalization of the Suez Canal. Zeinab Abd al-Hamid’s career was simultaneously rising in global prominence, with accolades including a nomination for the 1956 inaugural Guggenheim International Award, where she was one of five Egyptian painters selected as finalists. In 1958, thirty-nine year old Abd-al Hamid was amongst the elite group of artists chosen to represent Egypt and the United Arab Republic at the prestigious Venice Biennale. As the first Biennale following the revolution, Nasser’s brand-new Ministry of Culture sought to promote artwork that reflected his Pan-Arabic message, including Quartier Populaire amongst their selections. In the pavillion’s original pamphlet, Republique Arabe - XXIX Biennale De Venise, critic Salah Kamel attributed two essential forces of cultural acceleration to this collection: “active presence of a renewed spiritual vigor and enlargement of the sphere in which this force is destined to take place.” From her unique global perspective, Abd al-Hamid was empowered to act as a cultural ambassador, creating work that reflected Egyptian Modernism on an expanding global stage.

Zeinab Abd al-Hamid, an Egyptian Modernist painter best known for her vibrant cityscapes. Her artwork represents a post-revolutionary Egypt meeting the rest of the world. So what do we know about Zeinab?

Zeinab Abd al-Hamid's viivd paintings demonstrate the modernization of Egypt post-revolution, a blend of old traditions and new technology. Almost 20 years after her death, her paintings are still full of light and life.

To international critics, Abd al-Hamid’s expressive style and supersaturation can easily be compared to the French Fauvist movement, specifically the work of Raoul Dufy, as Karnouk recognized in her 1995 analysis Contemporary Egyptian Art. Yet like many other critics Karnouk made a point of remarking that Abd al-Hamid’s two-dimensional renderings without shadow were distinctly “Oriental.” In agreement with these remarks and those published by Kamel, al-Din Najib commented, “The painting may seem to us like a Mamulk tapestry, and . . . the folds of its delicate geometric motifs look like interstitial colorful spaces reminiscent of the Arabic mosaic.” Similarly, Ezzedin Hamouda fiercely defended the uniquely Egyptian aspects of both his and his wife’s styles. In an interview the professors gave while on sabbatical in Washington D.C., Hamouda argued that:

Our cultural development went parallel with the revolution of 1952. We refused to follow foreign trends and tried to create something genuine. We tried to conserve part of our cultural tradition, a unique mixture of pharaonic, Christian, Islamic and Muslim elements, without becoming dogmatic about it, without exploiting our heritage the way artisans and commercial artists often do . . . There is something ritual about oriental art. The lines and colors are clear and all parts are equal in our compositions . . . the sunlight in the East is strong. The outlines and colors are perfectly clear. You can see for miles in the desert. Gaug[u]in's work changed dramatically after he left Paris for the South Seas.

In this way, both painters challenged the popular post-colonial theory that inspiration could only travel from the East to the West. Abd al-Hamid exemplified this by choosing to join the faculty of the Academy of Arts in Helwan, Egypt in 1969. This re-investment in the next generation of artists, even as her work was increasingly demanded in lucrative global markets, speaks to her dedication to the future of Egyptian art. Yet her emphasis on hybridity continued as Abd al-Hamid was able to visit and exhibit work in Paris, Vienna, Budapest, Madrid, Washington, Florence, Rome, and New Orleans. Her work not only influenced how the world perceived Egyptian art, but also expressed how one Modern Egyptian woman saw the world.

Sources:

Al-Din Najib, Izz. ““Introduction: A Leading Artist in a Revolutionary Milieu.” In Painter

Zainab Abdel Hamid, Makram Haneen, 2018.

Azar, Emile. “Zainab Abdul Hamid Al-Zarqani.” Giza: Sector of Fine Arts, Ministry of Culture.

http://www.fineart.gov.eg/arb/cv/About.asp?IDS=217

Boukeshish, Mahmoud. “Zeinab Abdul Hamid and the Eye of the Bird.” in Al Hilal Magazine.

Cairo: Dar Al Hilal Publishing House, September 1998. http://www.fineart.gov.eg/arb/cv/About.asp?IDS=217.

Drath, Viola. “The Cairo Connection.” Originally published 25 November, 1977. Published

online by Khalda Hamouda in 2009. http://www.khaldahamouda.com/dossier.php.

Hamouda, Khala. “Egyptian Modern Middle Eastern Artist Zeinab Abd El Hamid.” Published

online in 2009. http://www.khaldahamouda.com/Zeinab.php.

Hamouda, Khala. “Oil Painter Ezzedin Hamouda.” Published online in 2009.

http://www.khaldahamouda.com/Ezzedin.php.

Hartman, Saidya. “Venus in Two Acts.” in Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 11.

Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Karnouk, Lilaine. “The Revolutionary Years.” In Contemporary Egyptian Art, 5-31. Cairo:

American University in Cairo Press, 1995.

Kamel, Salah. Republique Arabe 1958- XXIX Biennale De Venise, Venice: La Biennale di

Venezia, 1958. Translated from original Italian.

Safarkhan Art Gallery. “Zeinab Abdel Hamid.”

http://www.safarkhan.com/Artist-bio.aspx?artistid=562&type=exhibited. Accessed 06 March 2019.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Press Release. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim

Foundation, 13 November 1956. https://www.guggenheim.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/7november1956.pdf.

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.