It would be reductive to describe Lebanese artist Huguette Caland’s body of work as intentionally subversive. The veteran painter, illustrator, sculptor and fashion designer has effortlessly disrupted patriarchal norms by way of her colorful and explosive art.

But she’s seemingly less concerned with what she’s dismantled over the past half-century and more concerned with what she’s elevated: the female body, stripped of colonial clothing and other restraints.

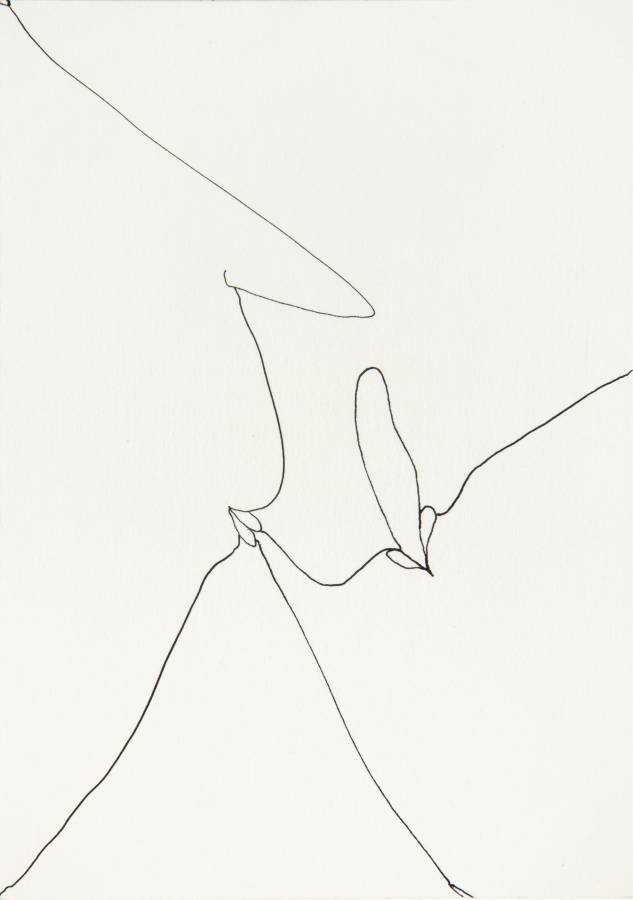

Caland’s Bribes de Corps (Body Parts) series from the early 1970s playfully toys with color, form, light, and lines in its glorious depiction of the female physique. You might even say the series – which features several “self-portraits” – serves as an ode-to-sexual-climax, reflecting Caland’s preoccupation with her own body and the bodies of those surrounding her. Caland refuses to tiptoe around red lines: instead, she takes hold of them and morphs them into overtly sexualized body parts.

Now an octogenarian pushing 90, Caland is finally being celebrated in mainstream Western art circles, once a place less welcoming to risqué female talent existing outside of familiar locales and genres. With the help of her daughter, Brigitte, Caland’s work is slowly but surely traversing the world: it was featured in New York at the Institute for Arab and Islamic Art last year and at the Venice Biennale in 2017, among other venues. It’s now being showcased for the first time as a solo exhibit in the UK at the bright and airy Tate Museum in St. Ives, a seaside town that since the Second World War has been closely associated with modern and abstract British art.

Deeply yet delicately erotic, Lebanese artist Huguette Caland's work hovers between figuration and abstraction, simultaneously challenging beauty and desire conventions

Caland’s work hovers between figuration and abstraction, simultaneously challenging beauty and desire conventions. Her work is deeply yet delicately erotic. The woman’s body is a vast landscape to be explored. Fields of warm-toned flesh contain subtle slits and curls where skin teases skin and lustful bodies greet one another. Place and time are rarely, if ever, a factor in Caland’s work.

The Beiruti artist was born in 1931 into high, francophone society. Her father was Bechara el-Khoury, Lebanon’s first post-independence president following a 23-year-long French Mandate in the Levantine country. Caland married into colonial-literati: her husband’s family published French-language newspaper L’Orient and was pro-French mandate. Ideologically, the Calands were quite the opposite of the el-Khourys, who were pro-independence (though she remained wed to Caland, Huguette would later take another lover, Mustapha, who is frequently featured in her work).

Throughout her career, Caland has been preoccupied with female emancipation. She came of age at a time when the notion of the tall, blonde-haired and thin-legged woman of the West was apparently desired by all, and so she struggled with her weight. Interviews with Caland screened at the Tate reveal that although she was never ashamed of her figure per se, she did retreat into herself as a teenager, as she felt society might shun her.

As a student, however, Caland was bold and precocious. When she and her peers were asked to pick a vegetable to draw for art class, Caland drew lettuce leaves, her daughter proudly recounted at the exhibit’s opening.

It wasn’t until Caland’s father died of cancer in 1964 that she decided to immerse herself more fully in her artistic endeavors. Following his death, she left her husband, lover and three children in Beirut at 40 and moved to Paris to explore her burgeoning talent. Her first painting was Soleil Rouge or Red Sun, also entitled Cancer, a sprawling canvas featuring intense and fiery bursts of red concentric circles. The uninhibited painting served as something of a gateway for Caland from one life to another: one devoted to her family and father, and another to herself and her art (Caland had nursed her ailing father for years, and remained by his side until he drew his final breath.)

“To become an artist was the toughest thing to do in Lebanon,” she once said of her decision to leave the country. “It was very difficult to establish myself as an artist in Lebanon when people knew that I was the daughter of my father, the wife of my husband, the sister of my brother, and the mother of my children. It was impossible.”

During the 1960s, before leaving to Paris, Caland threw out all her clothes, which she felt lacked authenticity due to Western and colonial influences. She rebuilt her wardrobe by her own hand, designing long, flowy abayas that would come to define her look. In Paris, Caland mingled with artists and designers – soon after Pierre Cardin met her, the French fashion designer commissioned a line of her kaftans, over 100 in total, two of which are displayed at the Tate.

The Tate show gathers art and textiles produced by Caland in the first 20 or so years of her career, from the sixties through to the mid-eighties, both before and after she left Beirut (Caland later lived in New York and California before moving back to Lebanon, where she currently resides).

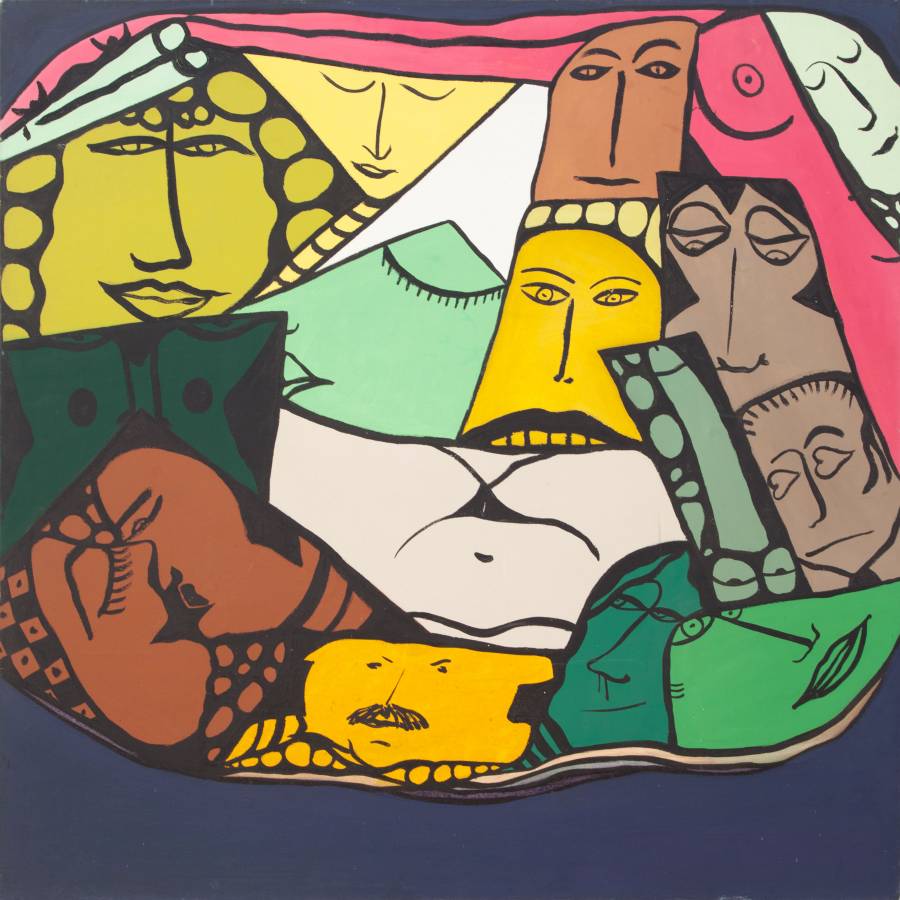

In the exhibit, Caland’s memory-infused works chart her growth as they delineate not only her own body parts but also those of her family, friends, lovers, and mentors. The art wavers between monochromatic illustrations containing solid black lines, and large plains of color, some of which are soft and muted, others bright and bold. Guerre incivile (Uncivil War), which depicts mangled, amputated bodies, is perhaps Caland’s most political work. The piece embodies the artist’s attachment to her homeland, despite (or perhaps due to) her having been estranged from it during the height of the Lebanese civil war.

At the Tate, Caland’s daughter Brigitte described her mother as “happy and content.” Simple though that description may be, there’s an energy to Caland’s work that bursts with just that: happiness and contentment, crowning achievements of a woman who has found herself in her liberation.

“There’s nothing that I’ve wished for that is not happening,” Caland said in an interview shortly after she turned 80. “And I think that’s incredible.”

Huguette Caland continues at Tate St Ives through September 1, 2019.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!