On April 4, 970, Fatimid General Jawhar al-Siqilli (or “the Sicilian”, as he was sometimes known) ordered the construction of Al-Azhar mosque in Cairo. Though certain periods have stood out in the history of the 1,000-year-old mosque, the story of its beginnings have remained largely obscure. What transpired during the Fatimid era of Al-Azhar? Who were its most prominent scholars during this period?

In his book The Role of Al-Azhar in Egyptian Politics, Saied Ismail Aly, a Professor at the Department of Education at Egypt’s Ain Shams University, stated that after the Fatimid conquest of Egypt, led by Jawhar al-Siqilli, and the establishment of the new capital in Cairo, the construction of al-Azhar mosque began in April 970 CE, and was completed in two years and three months.

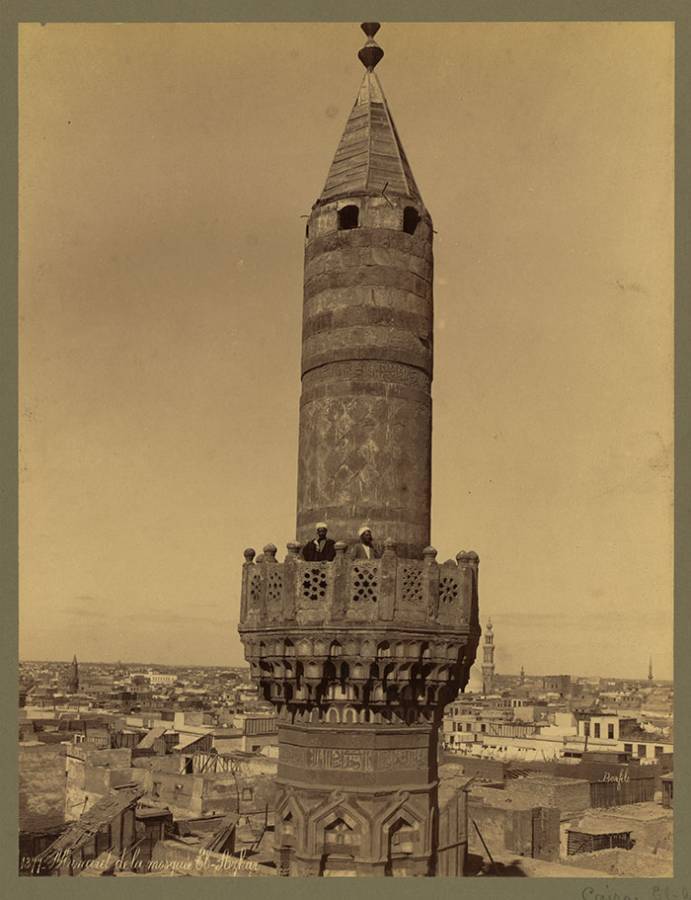

The mosque was first called al-Qahirah Mosque. When exactly the name changed to Al-Azhar remains unknown, and historians still debate the reason behind the renaming. Some historians suggest it was named after Fatimah al-Zahrā', the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, while others believe that the mosque was built in an area called Al-Qusour Al-Zahira (Lustrous Palaces), and was therefore named after it.

Political and Doctrinal Pronouncements

Saeid Ismail Aly notes in his book that the reasons behind the establishment of Al-Azhar were clear; the Fatimid state was a Shi’ite Ismaili caliphate, and al-Azhar was the first mosque built by Shi’ites in Egypt, thus turning al-Azhar into a symbol of a new religious empire. Against the symbolism of establishing Cairo as the beacon of a new state, al-Azhar began its teachings on the principles of Shi’ism.

Aly further notes that the Fatimids used al-Azhar as the center of their political doctrine, appointing dā’i al-du’āt (the head of the preachers) as the head of Ismaili doctrine, a position as important as that of qādi al-qudāt (chief justice). In most cases, both positions were occupied by the same person.

The head of the preachers held meetings and gave lectures in al-Azhar. He would also convene an assembly for women only, to teach them the Shi’ite Ismaili doctrine.

A Congregation Center

The Fatimid doctrine was based on the notion of the Imamate, i.e. the successors of the Prophet Muhammad in the leadership of the Islamic ummah (community). Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah would lead the Friday prayers without fail, as well as the prayers held during Eid al-Fitr, and Eid al-Adha at al-Azhar. He also preached in the mosque during Ramadan gatherings and holidays.

During the Fatimid era, Al-Azhar served as more than a mosque and a university; it was a center for official events.

This called for the creation of the rank of Muhtasib; the third highest religious ranking, following qādi al-qudāt, and dā’i al-du’āt. His duty was to oversee the promotion of virtue and the prevention of vice.

Al-Azhar was at the hub of religious celebrations such as the Birth of the Prophet. On the 12th day of the Hijri month Rabī‘ al-awwal, the qādi would head to al-Azhar, accompanied by servants carrying dessert trays, which were prepared in the Palace of the Caliphate. The desserts were handed out to the attendees of the celebration, including qādi al-qudāt, dā’i al-du’āt , and the readers of the Quran, before they headed to the Palace of the Caliphate.

The Fatimid state’s most famous season was dubbed layali al-waquod (fire nights); i.e. the nights preceding the beginning and middle of the Hijri months of Sha’ban, and Ramadan. All the mosques would be lit after sunset, bathing Cairo in a robe of light, people would head to al-Azhar, which would be lit up with torches. Meanwhile, inside al-Azhar, a council would be held by qādi al-qudāt, attended by judges and scholars.

Egyptians received these events with joy, with the exception of the day of 'Ashura, which was considered a day of public mourning. Markets would be closed for the day, and chanters would head to al-Azhar to lament the death of al-Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad and the third Shi’ite Imam. A meal of sorrow would be held in a simple hall, where barley bread, lentils, and cheese were offered. The Caliph would arrive masked and dressed in dark clothes.

Al-Azhar and Dar al-Hikmah

Aly continues in his book, stating that Ya'qub ibn Killis, one of the Viziers of al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah and his son al-Aziz, was the first to come up with the idea of making al-Azhar a hub for the structured, systematized study of Islam and the Shi’ite doctrine. In 988 CE, Ibn Killis asked al-Aziz for permission to appoint a council of scholars for the study and teaching of the Quran. The council would attend assemblies, which would be held in al-Azhar every Friday after prayers, lasting until the ‘asr prayer (late afternoon).

This Council consisted of 37 scholars, headed by the faqih (jurist) Abu Yaqub al-Aziz, who provided scholars with monthly salaries, and established a house where they could reside next to al-Azhar.

The doctrine of al-Azhar went into decline when the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah established Dar al-Hikmah (literally translating to the House of Wisdom) in 1005 CE. The name was meant to distinguish it as a symbol for Shi’ite proselytizing.

Dar al-Hikmah was endowed with a library known as Dar al-'Ilm (the House of Knowledge). The library comprised an extensive collection of books on various topics, including the sciences, literature, jurisprudence, grammar, language, chemistry, and medicine. The library was public, and permission to use it was granted to all.

Its role was to spread the Shi’ite doctrine in an organized, educational manner, and it was headed by dā’i al-du’āt. Subsequently, it replaced al-Azhar as the platform for Shi’ite proselytizing.

Prominent Figures from the Fatimid Al-Azhar

According to Aly, toward the end of Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah’s rule, in October 975 CE, qādi al-qudāt Abu al-Hassan Ali bani al-Nu’man al-Qayrawani called an assembly in al-Azhar, where he read a summary of Shi’ite jurisprudence from a book nicknamed al-Ikhtisar (The Summary) in the presence of a number of scholars and prominent figures.

This was the first lecture in al-Azhar, and was followed by a string of lectures by al-Nu'man’s followers. They were known as the elite of Morocco’s most respected scholars, and were strategically selected by the Fatimid state, employing them as their spiritual mouthpieces.

In 980 CE, Yaqub ibn Killis also called an assembly, and read from his book al-Risala al-Waziria (Ministerial Message). Judges had to rely on this book in issuing religious verdicts, while students and teachers had to study it.

Ibn Killis would alternate between holding his assemblies at al-Azhar and his palace. These assemblies were attended by jurists, judges, and senior state officials. Poets sang their praises at the end of the assembly.

The majority of scholars during this period were jurists and judges. Mosques became cultural centers, sought by scientists, writers, and particularly Shi’ite jurists.

In his book The History of Al-Azhar Mosque, Mohamed Abdullah Anan states that one of the most prominent figures during this era was linguist Abu al-Hassan Ali b. Ibrahim b. Saeid. Another was Abu al-Abaas Ahmed b. Ali b. Hashem al-Masri, who was famous for teaching Quranic recitation methods.

He noted that jurist al-Hassan ibn al-Khatir al-Farsi was also one of the most prominent figures, due to his knowledge of Hanafi jurisprudence and interpretation. He was also well-trained in mathematics, medicine, linguistics, and history.

The Role of Al-Azhar

Al-Azhar had an operative role in directing ideology in Egypt during the Fatimid era, according to Anan’s book The History of Al-Azhar Mosque, particularly as al-Azhar enjoyed an official status. However, this impact became limited, with the establishment of Dar al-Hikmah, which led the way in shaping ideology.

He added that al-Azhar’s impact was more powerful in spreading religious sciences and graduating religious scholars, as it was a domain for religious culture, while Dar al-Hikmah was more concerned with civil culture. Historians are largely in consensus over the fact that al-Azhar’s influence over scientific and literary development during the Fatimid era was significant, albeit not as significant as the influence it would pose in the future.

However, al-Azhar’s influence on the public sphere was modest, as the Fatimid Caliphate was committed to preventing the influence of scholars and clerics on politics.

The End of the Fatimid Al-Azhar

Saladin al-Ayyubi overthrew the Fatimid state in 1169 CE, taking over Egypt and realigning it with the Sunni doctrine. The Ayyubids would subsequently eliminate all of the Shi’ite rituals, bringing an end to the Friday prayers and preaching in al-Azhar. Its role was to be replaced by al-Hakim Mosque.

Al-Azhar lost its official ranking in the new Ayyubid state, and what followed was a period of stagnation prior to the reemergence of the al-Azhar institution in its Sunni form.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!