This investigation was conducted in partnership between ARIJ, Bab Masr, and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

At the turn of the 19th century, a German naval officer named Johannes Behrens set off on a winding voyage around the Mediterranean and beyond. The Bremen-born sailor wasn’t just a military man. He had an uncanny eye for antiquities. As he traveled, he bought remarkable treasures: an intricate Roman silver bowl, exquisite Ancient Egyptian carved sculptures, an ornate Greek bronze mask.

The gilded sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, stolen a decade ago and recovered by Egypt from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. It is now on display at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. | Photo credit: Mahmoud Bakkar / German Press Agency

The gilded sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, stolen a decade ago and recovered by Egypt from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. It is now on display at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. | Photo credit: Mahmoud Bakkar / German Press Agency

The gilded sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, stolen a decade ago and recovered by Egypt from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States. It is now on display at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. | Photo credit: Mahmoud Bakkar / German Press Agency

His collection was so impressive that it ended up on display in some of the world’s most prestigious museums. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, "Behrens Collection" was showcased in the world’s most notable museums and galleries. But new evidence has emerged in recent years that the German sailor never collected the objects attributed to him. In fact, he may never have existed at all.

According to French and American investigators, the objects supposedly bought by Behrens were actually smuggled by a ring accused of looting and trafficking antiquities out of Egypt. In late 2023, an elderly art dealer named Serop Simonian, who ran a shop in Hamburg, Germany—not far from where Behrens was likely born. Simonian was arrested and charged in France for trafficking multiple antiquities attributed to the German sailor’s collection.

For years, numerous artifacts sold to private collectors and museums were attributed to a German naval officer who was said to have acquired them in the early 20th century before passing them down to his heirs. However, ongoing investigations suggest the sailor might not have been real.

Simonian and other alleged members of the ring have denied the allegations, but the investigation is still ongoing. Though Simonian’s case has been widely reported, a number of objects ostensibly collected by Behrens—including one of which sold for over $200,000—have not been publicly identified, OCCRP’s partner in the Middle East, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), has found.

These objects include a Roman bowl sold by Christie’s auction house in 2010, a Hellenistic Greek marble carved stone slab sold by Christie’s in 2012, and a Greek-Roman bronze mask acquired by Italy’s Sorgente Group Foundation in 2010.

Ornate engravings and inscriptions

ARIJ was also able to identify the antiquities by searching publicly available data from auction houses and other institutions for mentions of Behrens. None of the three objects have been flagged by American or French investigators because they are outside their jurisdiction.

A Roman bowl from the 3rd century AD, sold for over $230,000 in 2010 and attributed to Behrens. | [Featuring a finely hammered relief of a priest dragging a goat to the temple of Minerva while the sun god Helios drives his chariot through the sky above, the piece was attributed to the "Behrens Collection." The description said the piece was acquired by the family of a woman described as the granddaughter of Johannes Behrens, "a seaman and 1st officer" who was "sailing routes in the Mediterranean to South America" from 1908 to 1939.]

A Roman bowl from the 3rd century AD, sold for over $230,000 in 2010 and attributed to Behrens. | [Featuring a finely hammered relief of a priest dragging a goat to the temple of Minerva while the sun god Helios drives his chariot through the sky above, the piece was attributed to the "Behrens Collection." The description said the piece was acquired by the family of a woman described as the granddaughter of Johannes Behrens, "a seaman and 1st officer" who was "sailing routes in the Mediterranean to South America" from 1908 to 1939.]

A Roman bowl from the 3rd century AD, sold for over $230,000 in 2010 and attributed to Behrens. | [Featuring a finely hammered relief of a priest dragging a goat to the temple of Minerva while the sun god Helios drives his chariot through the sky above, the piece was attributed to the "Behrens Collection." The description said the piece was acquired by the family of a woman described as the granddaughter of Johannes Behrens, "a seaman and 1st officer" who was "sailing routes in the Mediterranean to South America" from 1908 to 1939.]

A Hellenistic Greek marble funerary stele from the second half of the 1st century BC, sold in 2012 for over £60,000 and also attributed to the "Johannes Behrens collection" sold at Christie's in 2012 for over 60,000 British pounds. The carved stone shows the deceased person accompanied by two women, one of whom is touching her arm in a gesture of farewell.

A Hellenistic Greek marble funerary stele from the second half of the 1st century BC, sold in 2012 for over £60,000 and also attributed to the "Johannes Behrens collection" sold at Christie's in 2012 for over 60,000 British pounds. The carved stone shows the deceased person accompanied by two women, one of whom is touching her arm in a gesture of farewell.

A Hellenistic Greek marble funerary stele from the second half of the 1st century BC, sold in 2012 for over £60,000 and also attributed to the "Johannes Behrens collection" sold at Christie's in 2012 for over 60,000 British pounds. The carved stone shows the deceased person accompanied by two women, one of whom is touching her arm in a gesture of farewell.

A Christie’s spokesperson said they had no comment on the cases but added that “in general, Christie’s takes these matters seriously." The Sorgente Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Tess Davis, executive director of The Antiquities Coalition, a campaign group, said that with rare exceptions, antiquities on the market had been obtained illegally at some point—often looted and plundered from archaeological sites, graves, temples, or other sources.

"There are surprisingly few legal sources of antiquities, despite a large, legal market," Davis said. This created an incentive for criminals to "launder" antiquities by disguising their real origin.

"False documentation, including creating ‘historical’ collections or collectors out of thin air, is crucial to such fraud,” Davis added. “After all, it’s much easier to forge a provenance than it is to forge an artifact."

King Tut’s Stele

In 2017, the French Egyptologist Marc Gabolde came across a tweet written by fellow Egyptologist Susanna Thomas shared that she had been surprised to come across a previously unknown carved stone, known as a stele, dating to the reign of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, in the Louvre Abu Dhabi. His interest was immediately aroused.

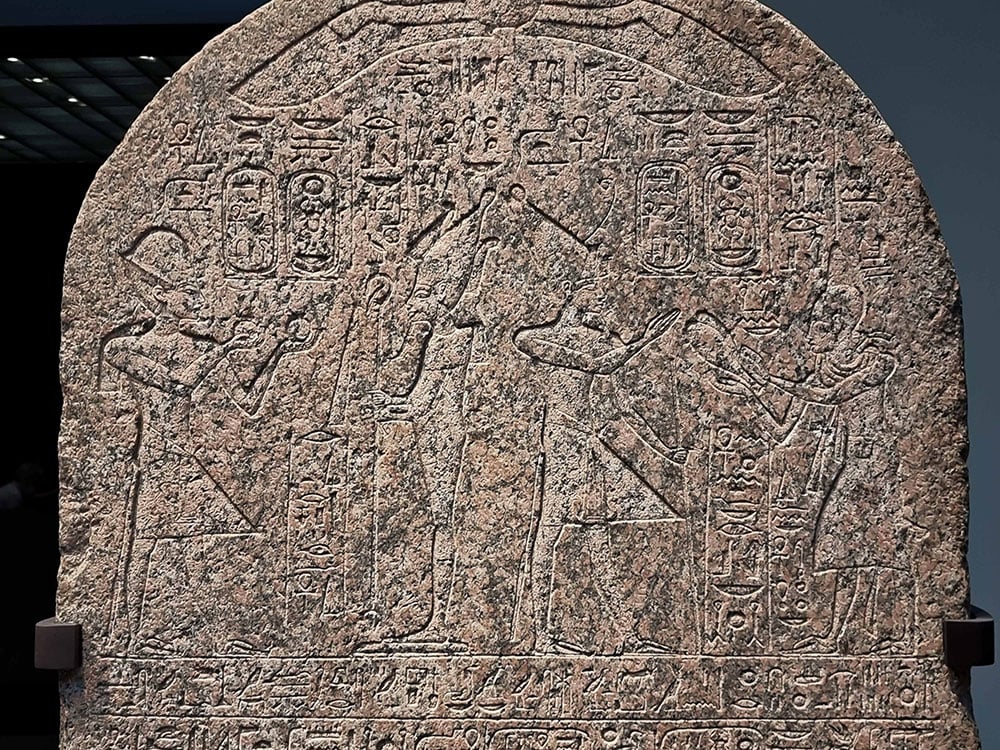

A carved stone, or stele, dating to the reign of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, displayed at the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Photo credit: Richard Mortel / Flickr.

A carved stone, or stele, dating to the reign of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, displayed at the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Photo credit: Richard Mortel / Flickr.

A carved stone, or stele, dating to the reign of Pharaoh Tutankhamun, displayed at the Louvre Abu Dhabi. | Photo credit: Richard Mortel / Flickr.

It was striking that such a fine piece would appear in a prominent institution without scholars being aware of it. (The Louvre Abu Dhabi uses the Louvre brand name and receives other support under a French-Emirati agreement.)

“Does anyone know ANYTHING about this? Abu Dhabi Louvre displaying a lovely stela with #Tutankhamun that we've never heard of before (!!),” Thomas wrote on Twitter, now known as X.

The stele was attributed to an Egyptian dealer, Habib Tawadros, who was said to have sold it to the German sailor Behrens in 1933.

Curious, Gabolde looked into the piece’s origins, but could find no sign of Behrens in any of the public records he reviewed. He expressed his doubts over the ownership of the stele to the Louvre Museum, but received no response.

"False documentation, including creating ‘historical’ collections or collectors out of thin air, is crucial to such fraud. After all, it’s much easier to forge a provenance than it is to forge an artifact."

The French authorities subsequently began their own investigation into the licenses relating to artifacts which had been sold to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, including the King Tut stele.

This culminated with the Louvre’s former president being charged with trafficking in 2022. The following year, a French court rejected his appeal to have the charges dismissed.

Former Louvre President Jean-Luc Martinez. Credit: Etienne Laurent/Pool/Abaca Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Former Louvre President Jean-Luc Martinez. Credit: Etienne Laurent/Pool/Abaca Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Former Louvre President Jean-Luc Martinez. | Credit: Etienne Laurent/Pool/Abaca Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Simonian, who owned the Dionysos Gallery of Ancient Coins and Antiquities in Hamburg, was arrested in September 2023 and charged with coordinating the illegal sale of artifacts, including the King Tut stele for 8.5 million euros (9.2 million US dollars). He has denied the charges.

The French investigation is ongoing, prosecutors told OCCRP. In May 2024, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office said it had returned 10 objects to Egypt based on information gathered from the case.

The mysterious identity of the elusive German sailor

In his defense, Simonian claimed his family had collected the objects in the 1970s, and produced documents showing Behrens had purchased them legitimately from Tawadros.

Tawadros does indeed appear to have dealt in antiquities—he is referenced in books and documents from the time, including a 1950s advertisement for his shop in “The Egyptian Tourist’s Companion.” But a source from the French investigation, who requested anonymity, said that investigators could not find any evidence Tawadros was active in the 1930s.

Since the investigations became public, other high-profile artifacts attributed to Behrens have come under scrutiny, including a painted Egyptian funerary mask purchased by Swiss billionaire Jean-Claude Gandur for nearly €1 million. In 2022, Gandur stated that he now believes the artifact's provenance was fabricated.

In New York, another scandal broke out when investigators found evidence that a golden coffin of the priest Nedjemankh—the centerpiece of a 2018 show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—may have been looted. The piece was removed from display and sent back to Egypt before the exhibition was even over.

In a letter to Egypt’s minister of antiquities, obtained by ARIJ, New York’s district attorney wrote that its investigators had found the license Simonian claimed was valid had a number of inconsistencies, including mismatched dates and a government stamp that said “AR Egypt,” though Egypt was known as the “United Arab Republic” at that time, with official stamps reading "UAR."

The golden sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, returned to Egypt. Credit: Xinhua/Ahmed Gomma/Imago/Alamy Stock Photo

The golden sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, returned to Egypt. Credit: Xinhua/Ahmed Gomma/Imago/Alamy Stock Photo

The golden sarcophagus of the priest Nedjemankh, returned to Egypt. | Credit: Xinhua/Ahmed Gomma/Imago/Alamy Stock Photo

Since the investigations became public, the origin of other prominent objects attributed to Behrens have also been called into doubt.

These include a painted portrait, used as an Egyptian funerary mask, which the Swiss billionaire Jean-Claude Gandur bought for nearly one million euros. In 2022, Gandur said he could find no evidence that Behrens existed and that he now believed the painting’s origins were forged.

An ancient table leg with the head of a goat carved into it, attributed to Behrens, was acquired by Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 2010. The listing now notes that media reports have “cast doubts on the veracity of this ownership history.”

“The US State Department revealed that documents on the ownership history of the piece are of questionable authenticity, which may indicate new archaeological looting,” Karen Frascona, the museum's director of marketing and communications, told ARIJ.

Byzantine-era painting fragments depicting the Biblical crossing of the Red Sea, acquired by New York’s Met in 2014, were also attributed to the sailor. They have since been returned to Egypt.

Davis notes that developing “a stronger, more transparent legal market would absolutely hurt the black market” for antiquities. But firmer regulation would be needed, too. At the moment, buyers of antiquities don’t benefit from the same anti-money laundering protections that are standard for other high-risk goods such as jewelry and precious metals, she said.

“Antiquities can easily surpass the value of a car or real estate, but unlike them, good titles can be incredibly difficult to prove,” she said. “If buyers and sellers are treating art and antiquities as an asset, the law must as well.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!