"On the morning of April 12, 2024, my colleague and I headed to the city of Rafah, south of the new area in Nuseirat refugee camp. We rode the press-marked vehicle to reach the displaced people and document their suffering, as well as the massacres being committed against them."

This is how the third day of Eid al-Fitr began for journalist Sami Shehadeh, 36, from Gaza City. Shehadeh has worked as a photojournalist for over 18 years and was covering the ongoing genocide on Gaza for Turkish state television TRT.

"I was covering the Great March of Return in 2018 while wearing my protective vest. I was standing in clear sight of Israeli soldiers in press gear when I was suddenly targeted directly by a sniper. I was hit by two bullets, one in my right leg and the other in my left. After three years of surgeries and treatment, I returned to photojournalism with a severed leg. The injury didn’t kill me; it made me stronger."

"We stopped more than two kilometers away from where the Israeli army had advanced to avoid putting our lives at risk," Shehadeh tells Raseef22.

He scanned the area through his camera lens but spotted no military movement. Just as he put his camera down, he heard the sound of a shell falling above him.

"I looked down at my right leg, and it was severed, completely gone below the knee and bleeding profusely," Shehadeh recalls. He dragged himself a few meters away from the area toward a side street.

Using his belt, he tied his leg in a tourniquet to reduce the bleeding. Colleagues and local residents soon arrived to help, attempting to further bandage the wound in an attempt to stop the bleeding and save his life. They rushed him to Al-Awda Hospital in Jabalia, and from there, he was rushed to Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah.

"I hoped my leg would be restored after the operation, but when I woke up, I found my leg had been amputated above the knee," Shehadeh says. He was supposed to continue his treatment abroad, but then the Israeli army closed the Rafah crossing, his only gateway to the world.

Israel’s targeting of civilians participating in the Great March of Return, which began near the eastern border of Gaza City in 2018, was what drove Hazem Suleiman to pursue a career in journalism. "I wanted to document the violations committed against civilians demanding the end of the siege on the Gaza Strip," Suleiman explains.

Shehadeh immediately returned to work with a missing leg and his trusted companion, the camera, resuming live broadcasts to cover the ongoing war and massacres Israel is committing.

Other journalists who lost their legs in previous wars can still be seen in the field in their vests and helmets, covering and moving from one massacre to the next and from one targeted area to another. Their numbers join the hundreds of journalists wounded in Israel’s successive wars on Gaza, alongside the 136 other journalists who have been martyred since October 7, 2023.

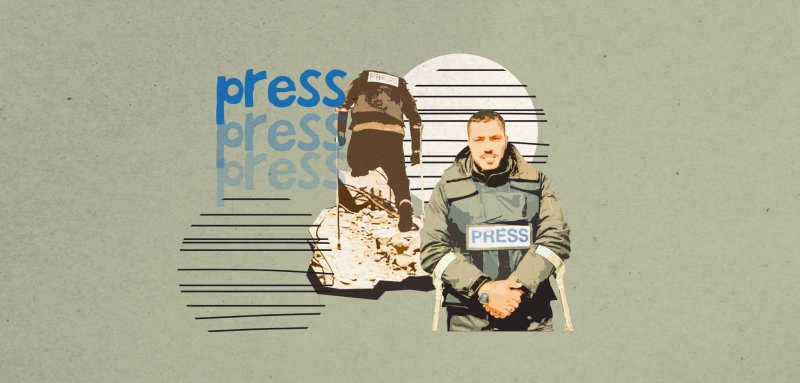

Photojournalist Sami Shehadeh | Source: Reuters

Photojournalist Sami Shehadeh | Source: Reuters

Photojournalist Sami Shehadeh | Source: Reuters

Losing their legs while covering the war

Hazem Abdullah Suleiman, 26, from Rafah, is one of these journalists. "After being forced to stop working for three years, I returned to photojournalism with an amputated leg. The injury didn’t kill me, it made me stronger," he tells Raseef22.

Israel’s targeting of civilians participating in the Great March of Return, which began near the eastern border of Gaza City in 2018, was what drove Suleiman to pursue a career in journalism. "I wanted to document the violations committed against civilians demanding the end of the siege on the Gaza Strip," Suleiman explains.

Journalist Sami Shehadeh heard the sound of a shell above the press vehicle next to them. He recalls, "I looked down at my right leg, and it was severed, completely gone below the knee." He dragged himself while bleeding profusely toward a side street to escape the Israeli military's attacks on the press.

He began working for British and Spanish news agencies. However, in July 2018, only a few months into his work, he was permanently disabled.

"I was covering the Great March of Return in the Malka area, east of Gaza, wearing my protective vest. I was standing in clear sight of Israeli soldiers in press gear when I was suddenly targeted directly by a sniper. I was hit by two bullets, one in my right leg and the other in my left," Suleiman recounts.

After being injured, he was taken to the hospital, suffering from severe tissue damage and shattered bones and muscles in his legs. He was then transferred to Egypt, where he underwent surgeries over the course of two years, all of which failed, as he recalls. Eventually, his leg had to be amputated. He has since undergone four more amputation surgeries and still needs another due to bone decay.

“I decided I would not be defeated and got out of bed. I used crutches and returned to my fellow journalists and the camera I had missed, my companion of two decades. It is my eyes through which I see the world and a witness to my life-altering injury.”

Suleiman and Shehadeh's stories of returning to work despite their disabilities are similar to that of photojournalist Moamen Qreiqea, 36, from Gaza City.

Qreiqea has witnessed many wars and worked in journalism for nearly 18 years. But during the 2008 war, he lost his leg. "I was working with a service provider in the Middle East. In 2008, on the Day of Arafat, I was filming goods stranded near the Karni Crossing, close to the border fence in Gaza, when we were directly targeted by an Israeli aircraft. I was hit in both legs. One was amputated entirely, while only 10 centimeters remained of my other leg," Qreiqa says.

Journalist Hazem Suleiman

Journalist Hazem Suleiman

Journalist Hazem Suleiman

Rising from loss

Suleiman, a father of eight, describes the period of injury and treatment that forced him to stop working as catastrophic. "I entered a difficult psychological state. I had mixed emotions, especially since I was still at the beginning of my career as a photojournalist. I was eager to practice journalism and had big ambitions," he says.

He adds, "But the Israeli occupation crushed my dreams. I felt like I would never return to work, especially since I wasn’t able to fit a prosthetic leg."

Suleiman's family didn’t expect him to recover either, given the complex psychological state he was in.

"In 2008, I was filming goods stranded near the Karni Crossing, close to the border fence in Gaza, when we were directly targeted by an Israeli aircraft. I was hit in both legs. One was amputated entirely, while only 10 centimeters remained of my other leg."

With a tremble clear in his voice, Sami Shehadeh, a father of two young girls, says: “The feeling of being a normal person with two legs, only to suddenly find yourself missing a limb and left with just one leg, is extremely difficult.”

He adds, “It's a defect in the body, but it causes a defect in your entire life. I started to isolate myself from others, preferring to be alone so I wouldn’t hear any words that might upset or shake me, even slightly.”

Four months have passed since Shehadeh’s injury, and the pain in his leg remains. "But what pains me more is its absence," he emphasizes.

Shehadeh spent nearly a month in the hospital. “The atmosphere there was hard to bear. People were screaming in horror at the sight of the martyrs and the injured,” he recalls.

"During the period of my injury and treatment, I entered a difficult psychological state. I had mixed emotions, especially since I was still at the beginning of my career as a photojournalist. I had been eager to practice journalism and had big ambitions. But the Israeli occupation crushed my dreams. I felt like I would never return to work, especially since I wasn’t able to fit a prosthetic leg."

He adds, “At one point, I decided I would not be defeated, and I got out of bed. I used crutches and returned to my fellow journalists and the camera I had missed, my companion of two decades. It is my eyes through which I see the world and a witness to my life-altering injury.”

At that moment, Shehadeh’s colleague was preparing to go live on air for the channel. He insisted on filming it himself, "and that's what happened. I filmed the live broadcast, followed by many more standups in the days after I left the hospital," he says.

Despite needing assistance from his colleagues, and at home for basic tasks like sitting and standing, Shehadeh was determined to continue his work. He says he constantly fights the feelings and doubts that he could ever return.

“I have witnessed five wars and filmed countless horrific massacres against children, women, men, and peaceful civilians. However, my determination to continue stems from my belief that my professional mission and message aren’t over. I still have much more to offer,” says Shehadeh.

“I have witnessed five wars and filmed countless horrific massacres against children, women, men, and peaceful civilians. However, my determination to continue stems from my belief that my professional mission and message aren’t over. I still have much more to offer. Nothing can break me or prevent me from practicing my profession, not even disability. I won’t sit around waiting for help. I’ll keep filming, even if it’s on crutches.”

He continues, “Nothing can break me or prevent me from practicing my profession, not even disability. I won’t sit around waiting for help. I’ll keep filming, even if it’s on crutches.”

However, Shehadeh dreams of leaving Gaza and getting a prosthetic leg so he can return to work as he did before his injury.

Photojournalist Moamen Qreiqa also had to stop working and underwent treatment for nearly nine months. “But I returned to work in a wheelchair, with the encouragement of my wife, family, and friends. I couldn’t accept becoming just another number, killed or injured by the occupation,” he says.

“The feeling of being a normal person with two legs, only to suddenly find yourself missing a limb, is extremely difficult. It's a defect in the body, but it causes a defect in your entire life. The pain in my leg remains, but what pains me more is its absence."

One of the obstacles he faced when returning to work was the reluctance of some colleagues, who felt his presence hindered their movement while taking photos. Additionally, their environment was not suitable for people with disabilities who rely on wheelchairs.

Journalist Moamen Qreiqa

Journalist Moamen Qreiqa

Journalist Moamen Qreiqa

Capturing the frame and the moment

Regarding how his disability has affected his ability to practice photojournalism, Qreiqa says, "The angles I rely on have somewhat changed. Sitting in a wheelchair, I have a different perspective compared to someone who can move freely. To overcome this, I study the field and the event I intend to cover before I head there."

Qreiqa currently works as a photographer for Italy's Noor Agency and as a freelance photographer for several other agencies. He adds, "It's true that moving around in my environment has been challenging, but this quickly turned into a strength that inspires my colleagues who were injured and returned to work after their injuries to expose the crimes of the occupation."

"I hoped my leg would be restored after the operation, but when I woke up, I found my leg had been amputated above the knee." Journalist Sami Shehadeh was supposed to continue his treatment abroad, but then the Israeli army closed the Rafah crossing, his only gateway to the world.

The same goes for Hazem Suleiman, who adapted to his amputation and decided to return to work. He became active on social media platforms. "I continued to photograph and showcase the beauty of life in Gaza before the war. I worked as a freelance journalist for several outlets like Al Jazeera and Roya," he says.

Suleiman acknowledges that losing his leg makes it difficult to move quickly from one location to another and find the best angles for photographing. He also faces challenges in protecting himself from ongoing Israeli attacks. "It's not easy to choose the right angle when you're on crutches," he says.

He continues, "In my determination to keep working, I started using a bicycle with one leg. I trained myself to move and photograph while riding it. Since 2020, it has been my companion. With it, I capture the images and events of the ongoing genocidal war."

“I was forced to stop working and underwent treatment for nearly nine months. But I returned to work in a wheelchair, with the encouragement of my wife, family, and friends. I couldn’t accept becoming just another number, killed or injured by the occupation.”

Like his colleagues, Suleiman hopes the war will end soon, allowing him to undergo the surgery his leg requires abroad, and perhaps return to photographing Gaza as it once was—a beautiful city.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!