“‘There is a Trojan horse in Britain: Hardline Muslims' claims Patrick Christys." “Vile Muslim extremist with his own 'ARMY' plans to create an Islamic homeland under Sharia law.” “Radical British preacher Anjem Choudary was convicted of directing a terrorist group." These are all headlines major British news organizations have published over the last four months. They are also prime examples of the kind of articles the British public is used to reading.

The British press readily spreads false and Islamophobic information about British Muslims, relying on words such as “hardline, “radical,” and “terrorist” to describe them. In this feature, Raseef22 analyzes the polarizing way British media depict Muslims and how such coverage leads to a lack of trust in media entities.

Islamophobia in British media

“I definitely think there's a narrative,” says Imam and councilor Adeel Shah. “Unfortunately, I think there is a negative narrative when it comes to reporting about religion, particularly Islam in the media.” Shah has been an Imam for four years as part of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community—a faction of Islam whose caliph and headquarters are based in Tilford, England. He has worked in the community’s Press Office for five years and is one of many British Muslim leaders attempting to challenge widespread Islamophobia and Islamophobic media narratives in the UK.

The Muslim Council of Britain’s Media Monitoring Centre, a project that aims to promote fair coverage of Muslims in the media, attempts to track and debunk such narratives. It released a report on British media coverage of Islam and Muslims from 2018 to 2020. The report revealed that 59 percent of online articles and 47 percent of TV clips associated with Muslims or Islam had negative connotations. The report, which analyzed nearly 50,000 online articles and over 5,000 broadcasts from UK media, found that one in five articles associated Islam with terrorism or extremism.

The Muslim Council of Britain’s Media Monitoring Centre, a project that aims to promote fair coverage of Muslims in the media, attempts to track and debunk Islamophobic narratives. It released a report on British media coverage of Islam and Muslims from 2018 to 2020. The report revealed that 59 percent of online articles and 47 percent of TV clips associated with Muslims or Islam had negative connotations. The report, which analyzed nearly 50,000 online articles and over 5,000 broadcasts from UK media, found that one in five articles associated Islam with terrorism or extremism.

Negative and false coverage directly impacts the safety of British Muslims. On the one hand, it can play a role in how those who consume media view Muslims. According to Hope not Hate's 2023 State of Hate report, for example, 42 percent of 20,000 surveyed Britons “definitely” or “probably” believe that many European cities are under Sharia law control as “no-go” zones for non-Muslims. This conspiracy, popularized by Donald Trump, originally gained traction thanks to various media outlets. On the other hand, such coverage can lead to bigotry-fueled physical violence. Just last month after a Russian news site falsely associated the July mass-stabbing attack of a children’s dance class in Southport, Merseyside, with Muslims, a wave of anti-immigration riots spread for a few days across Britain. Rioters threw rocks at a mosque in Southport and shouted Islamophobic slurs.

Islamophobia Mirrored in British Politics

British mainstream media is not the only group that struggles to accurately depict Muslims.

The Conservative Party has a history of members of Parliament (MPs) making Islamophobic comments, such as former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s comments describing women who wear a niqab as “letterboxes” and Conservative MP Lee Anderson accusing London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, of being controlled by “Islamists."

Such comments are not only dehumanizing, they are politically exclusionary. As Mobashra Tazamal, the associate director of the Islamophobia watchdog The Bridge Initiative, argues, the Conservative party has not only signaled that tacit acceptance of institutional Islamophobia but that Islamophobia is permissible rhetoric in politics.

And while the Labour Party more vocally vows to combat Islamophobia, it has nevertheless hemorrhaged support from British Muslims since October 7. An October 2023 survey of 30,000 British Muslims showed a 66 percent drop in support for Labour in favor of Independent or Green Party candidates or not voting at all. The primary reason? Party leader Keir Starmer and Labour’s wavering stance on Israel’s genocidal campaign on Gaza.

General Distrust in British Media and News Avoidance

Since 2017 the number of people in the UK who avoid TV, radio, and print news has doubled to 46 percent. This news avoidance is especially prevalent in minority communities that do not feel they are accurately represented in the media. According to the Reuters Institute, across different markets, those who avoid the news say they do so because they think it can’t be trusted (29 percent). Those under 35 say the news brings down their mood (36 percent), while 29 percent of participants said they feel worn out by the news and 16 percent say it leaves them feeling powerless.

A popular example of what contributes to this growing distrust of the media is how the public perceives the fairness of media coverage of Israel’s war on Gaza. A recent YouGov poll commissioned by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community asked members of the public to compare media coverage of the Israel-Hamas war and Russia’s war on Ukraine. While 62 percent said that coverage of the Ukraine war was “Totally fair," only 33 percent gave this answer regarding coverage of the Israel-Gaza war. This lack of confidence in coverage coincides with an Edelman Trust Barometer report from January 2024, which found that out of 28 countries the UK trusted the media the least.

Misrepresentation of Muslims plays another role in the growing distrust in British media. "There are countless examples of how British media has misrepresented Islam and Muslims, whether that's with misleading headlines, outright Islamophobia, or a lack of basic knowledge about Islam,” says Atif Rashid, editor-in-chief of Analyst News and former social media lead at the BBC’s Today Programme. “And it's not always just the tabloids.”

A protester supports Muslim rights in London.

A protester supports Muslim rights in London.

A protester marches against Muslim bigotry at London anti-Trump rally. (Image by Alisdare Hickson)

Misrepresentation of Muslims plays another role in the growing distrust in British media. "There are countless examples of how British media has misrepresented Islam and Muslims, whether that's with misleading headlines, outright Islamophobia, or a lack of basic knowledge about Islam,” says Atif Rashid, editor-in-chief of Analyst News and former social media lead at the BBC’s Today Programme. “And it's not always just the tabloids.”

Adam, a young professional raised as a Muslim in Britain who requested partial anonymity, has also noted this phenomenon. “The main thing I've witnessed is how Islam is always portrayed as a monolith or a singular narrative. This is from outlets across the political spectrum.” Today, Adam continues, “The actions of one person often speak for you and your entire community whether you want them to or not.”

The popularization of such narratives has lent itself to the homogenization of Muslim perspectives and the generalization about Muslims in Britain in general.

“Outside of the religion, there's very little that would unite a Muslim from Indonesia, Pakistan, or Nigeria. Yet in the eyes of the British media, you would be classed the same by virtue of being a Muslim. I feel this often makes British Muslims feel isolated and mistrustful of the British press.”

“Outside of the religion, there's very little that would unite a Muslim from Indonesia, Pakistan, or Nigeria. Yet in the eyes of the British media, you would be classed the same by virtue of being a Muslim. I feel this often makes British Muslims feel isolated and mistrustful of the British press.”

Representation in the Newsroom

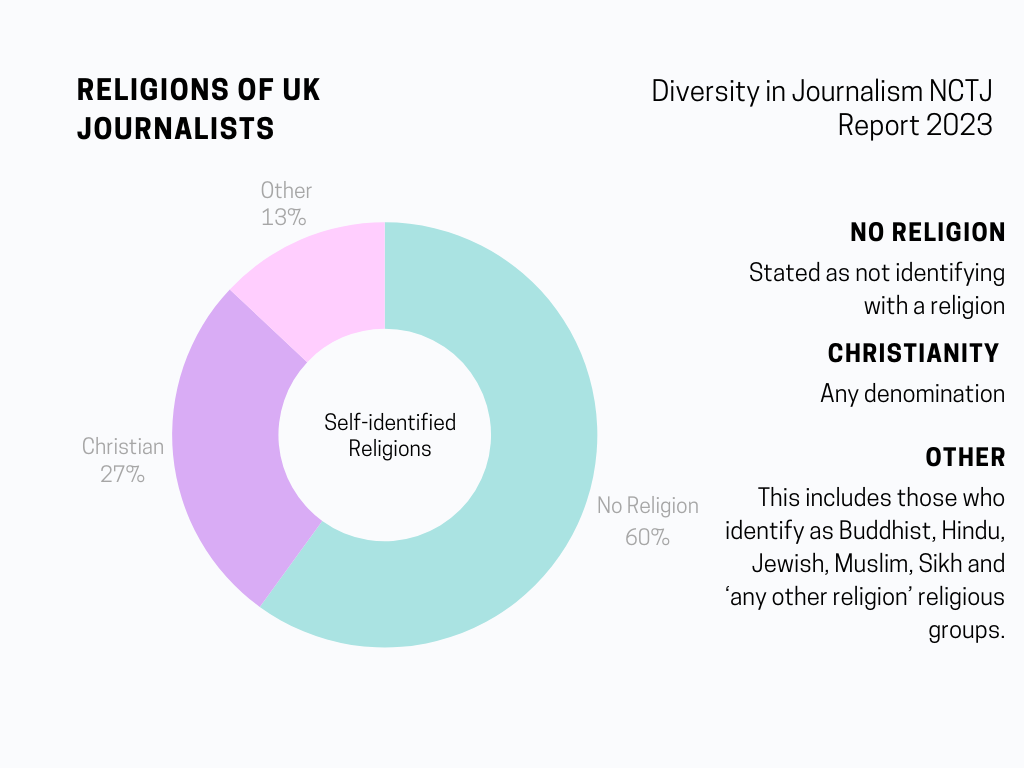

A possible reason behind why Muslims feel misrepresented in mainstream news is the lack of Muslim representation in newsrooms. As of 2023 in the UK, only 13 percent of journalists and 9 percent of editors identified as being part of a religion other than Christianity.

A graph depicting the religions of UK journalists based on a NCTJ report in 2023.

A graph depicting the religions of UK journalists based on a NCTJ report in 2023.

A breakdown of the religions of UK journalists based on data from the National Council for the Training of Journalists. (Image by Chloe Lovatt)

Rashid emphasizes that “Less than 0.5 percent of journalists in the UK are Muslim, yet a vast amount of stories are about Islam.”

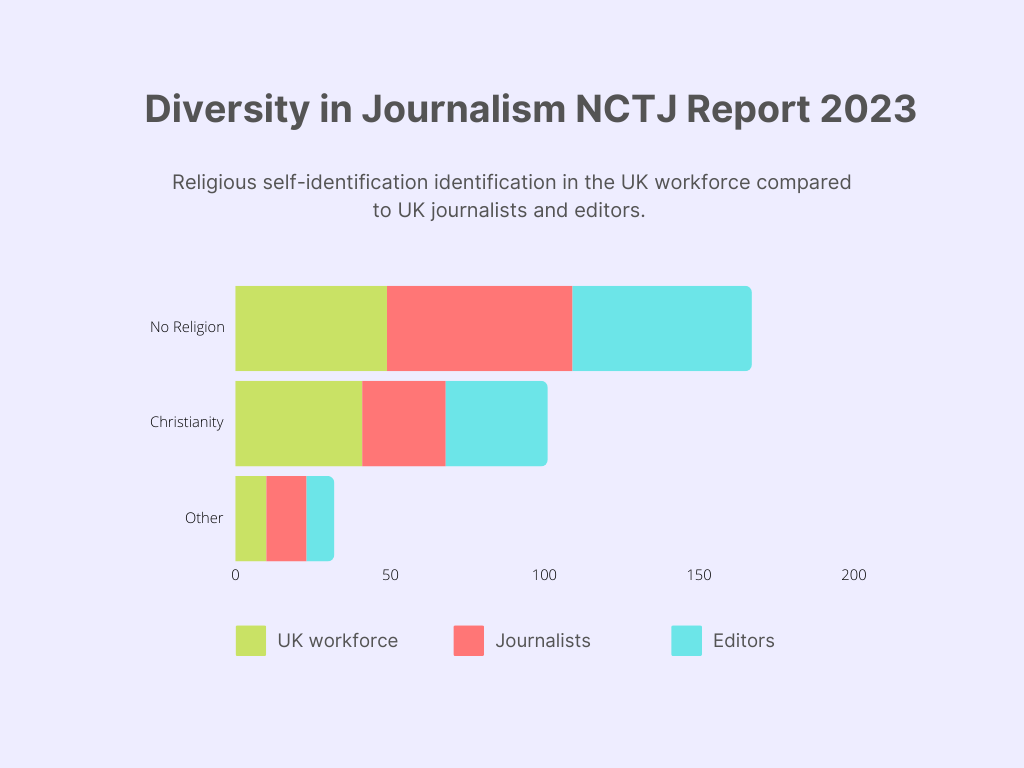

A graph depicting the diversity of UK journalists based on a NCTJ report in 2023.

A graph depicting the diversity of UK journalists based on a NCTJ report in 2023.

The religious diversity of the UK workforce broadly compared with UK journalists and editors based on data from the National Council for the Training of Journalists. (Image by Chloe Lovatt)

Shah, who also works as a fact-checker for media outlets about British Muslims, has encountered the effects of this lack of representation during his work.

“I've met journalists who've said, ‘Oh, before we spoke to you, when there was a story about Islam, we had no way to fact-check it.’ This is due to a lack of representation of Muslims in editorial boardrooms.” He and other journalists have been proactively contacting journalists to combat this.

Gaining back trust

So how can mainstream news outlets combat Islamophobia and gain the trust of the British Muslim population?

“There needs to be better representation within newsrooms and not just empty tokenism. We need to see more responsible reporting and better regulation,” argues Rashid.

Newsrooms must commission more stories from Muslim writers and seek out more Muslim sources to provide more diversity in perspective and open the pool to wider sources.

The power of this in creating more balanced media coverage was exemplified through the hit serial podcast “Trojan Horse Affair.” The podcast investigated the Trojan Horse letter, a supposed 72-page document outlining a plan to “Islamize” primary schools across Birmingham. One of the hosts, Hamza Syed, identifies as a British Muslim. Although it attracted some criticism for its journalistic practices, having a Muslim host investigating the case provided an alternative angle to the investigation. Syed’s background knowledge of the Birmingham Muslim community helped Muslim interviewees generally skeptical of the media trust him. Syed also provided social commentary based on his lived experience as a Muslim in the UK.

Shah frames the issue another way: “When we reach out to the media to say, ‘Do you want to report this positive, good story?,’ they often say, ‘No. Good news is no news.’”

Counteracting negative coverage by using “constructive” journalism, a form of reporting that focuses on providing solutions to societal issues, is another way to increase trust and readership.

The Guardian and The BBC trialed this approach in collaboration with The Constructive Institute. The BBC’s trial called ”Crossing Divides” produced stories about social cohesion across BBC platforms. A viral hit, the stories gained over 40 million views online and via social media. The Guardian found during its pilot of "The Upside" that the constructive approach increased readership and reader retention.

Ultimately, the British press has a clear path to increasing Muslim trust in media: expanding representation, using a diverse range of sources and journalists, and relying on fact-checked and verified information for stories. For the issue lies not in what British media can do to change Muslim distrust in the press; it lies in whether mainstream British media are ready to make such a change.

Ultimately, the British press has a clear path to increasing Muslim trust in media: expanding representation, using a diverse range of sources and journalists, and relying on fact-checked and verified information for stories. For the issue lies not in what British media can do to change Muslim distrust in the press; it lies in whether mainstream British media are ready to make such a change.

Shah frames the issue another way: “When we reach out to the media to say, ‘Do you want to report this positive, good story?,’ they often say, ‘No. Good news is no news.’”

*This article was edited and proofread with the assistance of Zoe Wolfsen.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!