The Problem: Why Headless Revolutions?

In the era of selfies, expecting younger generations to transfer their own decision-making powers to representatives seems unjustified. The phenomenon of the selfie—and the prioritizing of self-esteem behind it—displays that, in the younger generations, individuals consider themselves the most valuable and potential subjects of a work of art. Mona Lisa, by Da Vinci, symbolizes modern art because, for the first time, not a noble person but an ordinary woman could be the subject of a work. In the era of selfies, everyone is the Mona Lisa.

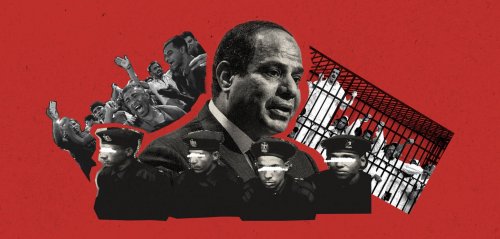

In the Arab Spring, Egyptian protesters created the “We Are All Khaled Said” movement. Khalid Said was an ordinary young man who was the victim of a brutal beating by the police. As the founder of the “We Are All Khaled Said” Facebook page describes, Khaled was someone with whom all Egyptian protesters could relate. They saw how every individual’s most valuable aspect—human dignity—can be disrespected by the Mubarak regime. Achieving equal dignity for everyone was the main goal of the Arab Spring Protests.

Achieving equal dignity for everyone was the main goal of the Arab Spring Protests.

The Arab Spring in Egypt and Mahsa Revolution in Iran display key elements of any revolution. The protesters do not wish to reform the system; they want to alter it drastically, at a foundational level, not because the regime is not reformable, but because the era, which I call the era of equal dignity, has arisen and the traditional style of sovereignty cannot function in this era. These two movements are headless revolutions. The revolutionaries deliberately avoided assigning leaders.

In the Mahsa Revolution in Iran, people chanted, “no Shan, No Rahbar, Democracy, Equality.” In this slogan, Shah represents the patriarchal monarchy (literally “Shah,” in Persian, means “king”), and the Rahbar (spiritual leader) represents the theocracy of The Islamic Republic. The slogan shows that protesters think that to solve the country’s current political problems, they need to go beyond the current political understanding of the raison d'être of society. The problem is not that authoritarian regimes of the region are not democratic; the problem is more fundamental than that. The problem is the insufficiency of this style of sovereignty which is coming to its end all over the globe. Modern liberal states were created to bring security to the people. This is the Hobbesian foundation for the existence of the state. To have a powerful state secure the lives of its citizens, they must give a part of their right to self-sovereignty to the state, and obey it, to allow the state to be able to defend them against internal and external threats.

When, in Iran, people chant, “I want my vote back,” what is meant is that the very concept of state sovereignty had become invalid. This fall of state sovereignty can be seen in the phenomenon of the headlessness of revolutions. Youth activists repeatedly have expressed that these revolution have no leader, not because of a lack of capable figures, but because the era of equal human dignity cannot accept the concept of leadership.

Now people in Iran and Egypt (and perhaps many other countries) do not want to give their sovereignty to their states. They do not want representatives. This is the spirit of this age. Classical state sovereignty over its subjects is coming to an end, even in the most democratic states of the world. This challenge of sovereignty is everywhere, but it shows itself first and most readily in non-democratic states such as Iran or Egypt.

When, in Iran, people chant, “I want my vote back,” it is not only a complaint about the correctness of this election or that election. What is meant is that the very concept of state sovereignty had become invalid.

This fall of state sovereignty can be seen in the phenomenon of the headlessness of revolutions. Since September 2022, when the death of Mahsa Amini triggered the uprising against the Islamic Republic, traditional political parties in the opposition have tried to offer their representatives as speakers or potential revolutionary leaders. However, the youth activists repeatedly have expressed that this revolution has no leader. These revolutions have no leader, not because of a lack of capable figures, but because the era of equal human dignity cannot accept the concept of leadership.

The revolution is completely leaderless, not in the sense that people see no potential in previous political figures to talk on behalf of the people, but in the sense that they see no reason to transfer their right to self-governance to a state. As Fatemeh Shams, an Iranian poet in exile, describes it: “people in the streets are not waiting for anyone to come and take the lead. They are the leaders of the revolution.”

This topic of headlessness goes back to the Green Movement in Iran in 2010 when Iranian voters protested against distorted presidential election results. In that movement, two reformist candidates who claimed that the regime had manipulated the election results in favor of a government-backed candidate were sometimes considered the movement’s leaders. However, this idea was discussed for the first time among protesters that the Green Movement should stay headless and those two opposing candidates (Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi) should be regarded as followers of the movement—like every other person—and not as the leaders of the Movement.

Both of the heroic figures of the Green Movement in 2010 and the Mahsa Movement in 2022 are female. Neda Agha-Soltan and Mahsa Amini were two victims whose deaths (by the government) triggered the uprising. Not only are the heroic figures female, but the most outstanding revolutionary figures of the movements are also women. One may wonder: What is the relation between the female-basis of these movements and their headlessness? Can one conclude that because women have always been suppressed in these countries, they are not sufficiently experienced and knowledgeable to lead social movements? Or is it that, because prominent figures are women, they intentionally keep the movement headless or leaderless?

Nasrin Sotoudeh, one of the influential figures in the Mahsa Movement and a human-rights lawyer who has represented many female activists arrested by the regime, believes this movement is intentionally leaderless because all Iranian women are leaders of this revolutionary act. And they pursue their egalitarian goals by the most traditionally non-political activism, they just take their scarves off their heads and walk in the streets of Iran. That is the kind of political activism which is in line with the era of human dignity.

In Egypt, youth activists deliberately tried to keep their revolution headless in order to keep the power in the hands of “the people.” They seemed uninterested in the procedural and organizational requirements of taking power, refraining from creating political parties or challenging the existing power through elections.

Although having no leader or being headless sometimes is considered a weak point for these social movements, the essence of these revolutions requires such headlessness. The revolutionary figures do not want to retread the traditional way of seizing power through traditional political machinations, raising themselves up as the new representative of the people. The youth revolutionaries insist they remain leaderless, which means achieving a new model of political life that surpasses the traditional political activism and political decision-making.

Similarly, in Egypt during the Arab Spring, the youth activists deliberately tried to keep their revolution headless in order to keep the power in the hands of “the people.” The youth movement in Egypt seemed uninterested in the procedural and organizational requirements of taking power. They intentionally refrained from creating political parties or challenging the existing power through elections.

The movement’s founders staunchly refused to be associated with political parties. In an interview, members of a youth-based association stated that political parties cannot represent public opinion or the revolution's demands. Political parties—by nature—act for their own benefit.

The name of the first anti-Mubarak movement in 2004-6 shows the end of this political era—they called their movement Kifaya, which means “enough.” The name indicates that people feel the need to close a long chapter of malfunctioning sovereignty and have a new political system which leaves no or minimal room for corruption and misuse of power.

However, based on the status quo of politics in Egypt, the youth movement of the Arab Spring suffered a significant disadvantage. On their way to freedom, they encountered well-established institutions and opposition parties who hijacked the movement in favor of their own ideologies. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt rallied behind the youth movement and opportunistically took power. They had an established and experienced leadership structure, which could mobilize and organize their members and control the current of events. They did and made the movement their own.

Although elected representatives are supposed to represent citizens and protect their cultural and economic interests, corrupt politicians exploit people and natural resources in the name of representative democracy. Those perennial problems of representative democracy, such as concentrated power, corruption, and lack of post-election accountability, have become cancerous in Middle Eastern semi-democracies.

The Problem of Centralization of Power in Middle Eastern Democracies

In the Iranian political structure, there is a closed loop. The people elect an Assembly of Experts. The Assembly of Experts elects the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Leader appoints the members of the Guardian Council who vet the candidates for elections of the Assembly of Experts. This structure obviously cannot satisfy the criteria of a free election because the Supreme Leader can have the final say over any issue.

The tribal nature of political structures in Iran has strong potential to corrupt any elected representative. The idealistic egalitarian revolutionaries in Iran’s 1979 revolution became corrupted oligarchs after a few decades due to the traditional tribal structures of political power in the country. During the 44-year life of the Islamic Republic, despite civil society’s continuous efforts to reach a democratic political system, election campaigns quickly became corrupt. Due to the corrupted structure of the election procedure, candidates could easily manipulate the election result. In Ahmadi Nejad’s presidency, his campaign could buy people's votes with a bag of potatoes in Iran’s rural areas.

Corruption is also present in all economic and social infrastructure. Amidst the 2022-2023 protests against the regime in Iran, the sudden fall of the under-construction Metropol tower in Khuzestan, resulted in dozens of people being killed just because the corrupt oligarchic owner did not follow construction codes.

In Egypt, the situation is the same. Any political stakeholders in power try to confiscate the power for themselves. The military, which took control of the country in the transition period between the Mubarak system and a new government with a new constitution always tried to secure its top members’ power. For instance, when an assembly was created to draft the new constitution, heads of the military attempted to secure their power and escape from any assessment and investigation based on law.

After the 2011 election in Egypt and its surprising result, the Islamist president Mohammad Morsi tried to exercise his power undemocratically. He forced many high-ranking military officers and judges to retire. His action upset the youth movement, which caused the toppling of the Mubarak system and opened the way for Morsi’s presidency.

During the Arab Spring, the youth activists distinguished the reason for their action from the reason of the previous generation. They believed that previous generations had always been interested in their personal gain in political activism. Corruption has become a substantial element of the state bureaucracy; it is standard practice in any administrative process; it is everywhere, penetrating everything from parliamentary elections to judiciary structure. For instance, the April 6th Youth Movement referred to all party men, politicians, and businessmen as “thieves” in their slogan.

Egyptian youth movements asked to recast state-society relations and remodel the political system because they believed that representative democracy causes corruption by its essence. Reform is not enough because as long as they stay in this governance model, no problem is solved. Based on this belief, any negotiation with Mubarak’s system was considered a betrayal.

In the Egyptian youth’s understanding, politics is, inherently, a competition to achieve power and benefit. The youth have concluded that not only are politicians corrupt, the political system—representative democracy—corrupts everyone.

In the Egyptian youth’s understanding, politics is, inherently, a competition to achieve power and benefit. The youth have concluded that not only are politicians corrupt, the political system—representative democracy—corrupts everyone.

This need for a new model of sovereignty is seen even in the best models of governance, as in American democracy. The very problem which James Madison, one of the founding fathers of the United States, saw at the very outset of the first modern democracy reaches its pinnacle in the Middle Eastern model of governance.

Madison believed that the idea of the Senate, which shows the British aristocratic roots of the American political structure, was harmful to democracy. He believed the House of Commons represents the people, and the House of Lords represents the aristocracy. The so-called Middle Eastern democracies show that aristocratic corruption quickly becomes cancerous in a representative democracy.

Toward a New Conception of The Political in The Middle East

In the Middle East, we see the need for new models of sovereignty. People no longer want to rely on traditional politics to manage their society. People want to get out of a social contract which has been beneficial for only one side.

Some may argue that it is time to return to direct democracy. If having a direct democracy was impossible due to historical-geographical barriers, now it is rendered possible thanks to public digital platforms. The youth in the Middle East have shown that they are very knowledgeable in using digital platforms to pursue their democratic goals. They could effectively use social media to organize their events, promote their values, protest against corrupted systems, and force the authorities to change their undemocratic policies.

In a recently published book, the Iranian political activist, Mehdi Jami, argues that Iran has been suffering from continuing centralization of power, even before the Islamic Revolution. First, it was under the monarchic system of the Shah and then under the theocracy of the Islamic Republic. Jami’s book can be regarded as one of the first notable theoretical steps to prescribe participatory or council democracy for addressing the problem of centralization of power in Iran. What he calls a council or community democracy encourages people to participate in the decision-making process of their society. Just voting for representatives is not enough. The decisions should be made by people, from the bottom up. These goals can be reached by creating a system of local, municipal, and provincial councils in which people can bring an idea to the fore, discuss it between themselves, vote for it, and send the result of their votes to a higher level of the system to be finalized as a law. Jami thinks that something like federalism, but in a more atomistic shape (like city-states), can be called council democracy, and it can solve the problem of corruption and power centralization in Iran. He emphasizes that Iran, a multicultural country with diverse religions and cultures, cannot reach a just and unbiased political structure without a participatory democratic form. In this semi-federalist participatory democracy, little parliaments can reach a consensus instead of a tyrannical majority imposing its opinion on minorities.

The revolution is completely leaderless, not in the sense that people see no potential in previous political figures to talk on behalf of the people, but in the sense that they see no reason to transfer their right to self-governance to a state.

Revolution for Egyptian activists meant something similar. It would be a transfer of sovereignty to the masses or relocation of power into the hands of the people. The Egyptian activists, during the Arab Spring, emphasized that the solution is participatory politics, power-sharing, and consensus decision-making. During the transition period, they tried developing governance models which were deliberately non-hierarchical. The groups like Kifaya, Youth for Change, and Revolutionary Socialists attempted to develop a power-sharing arrangement to generate active participation for all members. They deliberately avoid the emergence of leaders. They did so by creating numerous internal committees which were open to all members.

Tahrir Square was also a place for renewed enthusiasm for a new form of politics. People of all different social classes were able to meet and communicate with each other with equal dignity. Muslim, Christian and secular, poor and rich, educated and uneducated, the girl without Hijab and with Hijab, all gathered with equal rights and dignity to discuss their issues and vote for them. A co-founder of the April 6th Youth Movement describes Tahrir as a new utopia.

In Tahrir, the state-society relation changes to a new paradigm. The power that people once transferred to the state (according to social contract theory) is going back to people because the very concept of a social contract has lost its validity in the new era of political philosophy.

When we look at the leaderlessness of recent revolutions in the Middle East from the perspective of a new era in political philosophy, then we may recognize that leaderlessness is not a weak point for the recent revolutions. It is entirely in line with the nature of these revolutions, which put their efforts towards a ruler-free and contract-free structure of social order. Although it might seem a weak point in the status quo of politics in countries like Egypt, and some people may argue that, due to that problem, the youth movement was doomed to fail, in fact leaderlessness leads us to imagine a new shape for sovereignty.

This new shape can be an end-point for the entire history of social contract theory. Based on Rousseau and Locke’s social contract theory, people transfer a part of their freedom to the state because of the belief that they can emancipate themselves from the state of nature to the state of civil society. This social contract is valid as long as the state remains within the contract's terms, which brings citizens political, economic, and cultural security. When the state cannot meet the terms due to the inherent and inevitable problem of power centralization, the contract becomes invalid by default. This has happened for Middle Eastern States such as Iran and Egypt.

Hobbes threatens citizens, saying that if they step away from the contract, they will return to a state of nature and the war of all against all. This might not necessarily happen. People can take back the right to sovereignty from the state and remain in a state of civil society. If people can cooperate to manage their own affairs without transferring their rights to a third party, no raison d'être remains for the state in its traditional shape. Hanna Arendt opened the way to this new era of political philosophy through the concept of political action in which citizens participate freely and equally in public life and public decision-making. In this new polis sovereignty remains always with the people, and there is no ruler and ruled. This lack of ruler in a civil society is a new era in political philosophy. Ardent believes history of political philosophy has always been clustered around the concept of rule, the ruler, and the ruled. Rule by one is a monarchy, rule by few is an oligarchy, and rule by many is democracy. The problem is that the concept of rule rests on suspicion of true political action, which is citizens’ free and equal participation in public life and public decision-making.

It is the time to go beyond the dichotomy of the ruler and the ruled, even in the best existing democracies. This goes beyond the traditional concept of social contract. People want to keep the right to make political decisions in their own hands with no need for representatives.

Now the question for further steps is, what shape of government may this new era of politics have? Can participatory democracy work in this era? Many critics legitimately alert defenders of participatory democracy to pay attention to problems such as the insufficient political knowledge of the majority.

In answering this criticism, it is worth taking a look at one of the first successful cases of participatory democracy in the Middle East, which is not in Iran, nor Egypt; it is in Rojava, the self-governed Kurd region in the North of Syria. After the uprisings in Syria against the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad, Kurds in the north of Syria created an exemplary participatory democracy for the Middle East. The main element of their democracy is avoiding any centralization of power. Similar to what I explained above with respect to Mehdi Jami’s plan for participatory democracy in Iran, Kurds have created a structure of small and local councils at the lowest levels of their society, and the process of decision-making is entirely bottom-up.

In Rojava, there is no single leader. Even the chair of the councils is a pair of male and female members. They insist on collective leadership because they believe that any power centralization turns members' public duty into political careerism. To prevent this political careerism, they developed the mechanism of non-paid public offices. People perform their administrative duties voluntarily. Another exciting element of Rojava’s participatory democracy, which is in line with what I described in the previous section, is that they have done away with political parties. Instead of political parties, local communes assume decision-making roles.

To sum up, this phenomenon of leaderlessness refers to a new era in politics in the region. It is the time to go beyond the dichotomy of the ruler and the ruled, even in the best existing democracies. This goes beyond the traditional concept of social contract. People want to keep the right to make political decisions in their own hands with no need for representatives. They are educated enough and capable of figuring out what is politically right and wrong for their society. They claim the entitlement, enjoyment, and practice of this right by themselves, perhaps for the first time in the history of nation-states.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!