The historical interplay between the East and the West has often been confrontational and marked by conflict, stemming from mutual misunderstandings, with few attempts to thaw the ice. Orientalism was one of these attempts, but it was associated with occupation for a long time, so some describe it as “a factor and a moral excuse for colonialism.”

Orientalism, as defined by Edward Said in his book of the same name, is described as a tool wielded by the West to assert its "strategy (superiority), consistently placing the Westerner in a series of relationships with the East, where the Westerner always maintains the upper hand, and in a position of dominance in their interactions with the East."

For a long time, in Orientalist studies, Islam was commonly perceived as emblematic of the East, while Christianity was a representative of the West. The space in between the East and the West was fraught with tensions and clashes. As Samuel Huntington, the author of "The Clash of Civilizations", pointed out, "the relationship between Islam and Christianity was often tumultuous, with both sides regarding the other as 'the other'." Given that Muslims represented the primary competitors, according to Bernard Lewis, Europeans held varying perceptions of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad, or as they referred to him, "Mahomet." These perceptions evolved depending on the political context.

But where do we begin?

For a long time, in Orientalist studies, Islam was commonly perceived as emblematic of the East, while Christianity was a representative of the West, and the space in between the East and the West was fraught with tensions and clashes.

"God wills it"

The exact date of the first European text about Muslims remains unknown. However, some argue that the inception of such texts occurred during the conflict between Charlemagne and the Umayyad state in Al-Andalus. One notable example is the epic poem "The Song of Roland," which portrayed Muslims as ferocious monsters, labeling them "Mahometans" (a term that would persist into the early Renaissance), as it was believed that Muslims worshipped Prophet Muhammad alongside Apollo, the Greek god, and practiced polygamy, with the women marrying several men rather than men marrying several women.

This stereotypical image persisted, particularly among European philosophers and poets, during the downfall of the last Muslim stronghold in Al-Andalus in 1492. Subsequently, it returned to the forefront during the wars between Christian Europe and the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

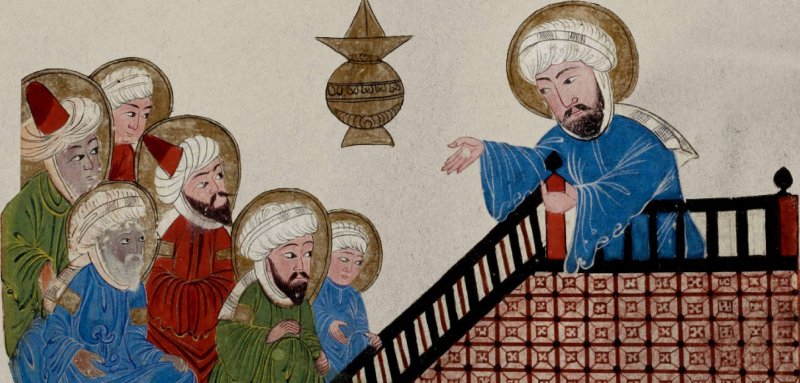

In his 2019 book titled "Faces of Muhammad," French academic John Tolan traces the evolution of Western European perceptions of Prophet Muhammad and the East. He covers nine chapters that span from deifying him to depicting him as a charlatan and deceiver, and ultimately recognizing him as a social reformer and revolutionary. These perspectives were profoundly influenced by the ongoing conflict between the East and the West.

This conflict gave rise to stereotypical perceptions of the East, most notably during the era of the Crusades, launched by Peter the Hermit. As Emad Sharaf recounts in his book "Facts About Evangelism", Peter the Hermit made a call to arms with the proclamation, "God wills it!" before forming a ragtag army, which served as the nucleus of the Crusades. "Then Pope Urban II reiterated this slogan, declaring it the slogan and rallying cry of the Crusaders, urging them to carry the cross on their chests as a symbol of their devotion. He stated, "Let it be your war-cry from this time forth; let the cross be your badge and symbol of immortality." The direction of these crusades was consistently towards the East, where Muslims were perceived as corrupt desecrators of Christian holy sites, including the alleged act of urinating on Christ's tomb, as claimed by Peter the Hermit.

With time, these campaigns advanced toward Al-Andalus under the banner of the "Reconquista" (Wars of Reconquest), resulting in a cultural crisis with the fall of one of the most significant centers of civilization. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche reflected on this in his work "The Joyful Science", stating, "Christianity has robbed us of the harvest of ancient culture and civilizations, and later it robbed us once again of the harvest of Islamic civilization."

The exact date of the first European text about Muslims remains unknown. Some argue that the first such text occurred in the poem "The Song of Roland," which portrayed Muslims as ferocious monsters, that worshipped Prophet Mohammad alongside Greek god Apollo

The moon in his sleeve

One of the most prominent fallacies made by Europeans during the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance was the logical fallacy of the "straw man". This fallacy involves creating a caricatured figure parallel to the actual person, then stripping the caricature of all the flaws and shortcomings attributed to the real individual, which is exactly what Voltaire, the French philosopher, did. Some Muslims claim that he began his life as a critic of Islam but ended up extolling it in his final work, "Voltaire's Philosophical Dictionary." In it, he vehemently states, "I say it again to you: O foolish and backward-minded people who have been convinced by some ignorant people that the religion of Muhammad is sensual and lustful! Not one word of truth lies in that."

However, in another chapter of the same book, he describes the Prophet Muhammad as a fraud: "Muhammad nearly failed twenty times, but in the end he succeeded with the Arabs of Medina, and the people believed that he was a close friend of the angel Gabriel. If any man today were to go to Constantinople and announce that he is the favorite of the chief angel Raphael, higher in rank than Gabriel, and that he alone must be believed in, they would put him on a stake in a public place. Hence it is up to the charlatans to choose the best time very carefully."

At other times, he depicts him as a cunning deceiver and a highwayman, perplexed by the public's admiration for historical figures like Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and "Muhammad, the deceiver, the highwayman, but he us the sole religious legislator with the courage to establish a great and formidable empire."

This is compounded by certain inaccuracies and contradictions that Voltaire stumbled upon, particularly when he mocked the mentality of the Mahometans (Muslims), under the mistaken belief that they thought Muhammad once placed the moon within his sleeve!

However, Voltaire was neither the first nor the last; rather, he was a product of a historical context fraught with misunderstanding. In his book "The Life of Muhammad," author Muhammad Hussein Haykal quotes Emile Dermenghem as remarking, "As war erupted between Islam and Christianity, differences and misunderstandings naturally deepened and intensified. We must acknowledge that the Westerners were the first to engage in the most severe disagreements. Among the Byzantines, some regarded Islam in contempt and disdain, without taking the trouble to study its essence."

As for the origins of this misunderstanding and its persistence, Edward Said, in his masterpiece "Orientalism," suggests that it was primarily politically driven: "Because Islam was consistently seen by them [the West] as fundamentally belonging to the Orient, its specific role within the broader framework of Orientalism was to first be perceived as monolithic, fixed, and not as it truly is – diverse. Then, after its diversity was acknowledged, it was viewed as a threat, and by becoming such a threat, it was made to appear increasingly rigid, then viewed with both hostility and fear."

………

Expressions of disdain from "Dermenghem" and apprehension from "Said" continue to surface from time to time. In his book "Modern Egypt," British consul Lord Cromer conveys a condescending view of the East and its Muslim inhabitants, remarking, "Ingratitude and a lack of appreciation by a people of their foreign benefactors are as old as history itself. No matter how great the moral harvest we may reap, we must, as St. Paul says, fulfill our duty, and that duty is clear ."

As for the element of fear, right-wing orientalist Bernard Lewis states, "For nearly a millennium, from the first Moorish landing in Spain to the second Turkish siege of Vienna, Europe faced an enduring threat from Islam."

The most famous error made by Europeans during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance was the logical fallacy known as the "straw man." This entailed creating a caricatured figure as a parallel to the real individual, which is what French philosopher Voltaire did

You are worse than the Arabian Prophet

The act of comparing someone to the Prophet Muhammad was long regarded as a mark of disgrace and a severe insult in the Western world. Even in the early 20th century, during political and denominational conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in the United States, Muhammad was used as a subject of ridicule and denigration. In his research paper titled "The Stereotypical Roots of Muslims in the American Mind," Muhammad Al-Shanqiti recounts John Quincy Adams' attack on President Thomas Jefferson, labeling him as "the Arabian Prophet," and how another Baptist minister referred to him as "a new Mohammed."

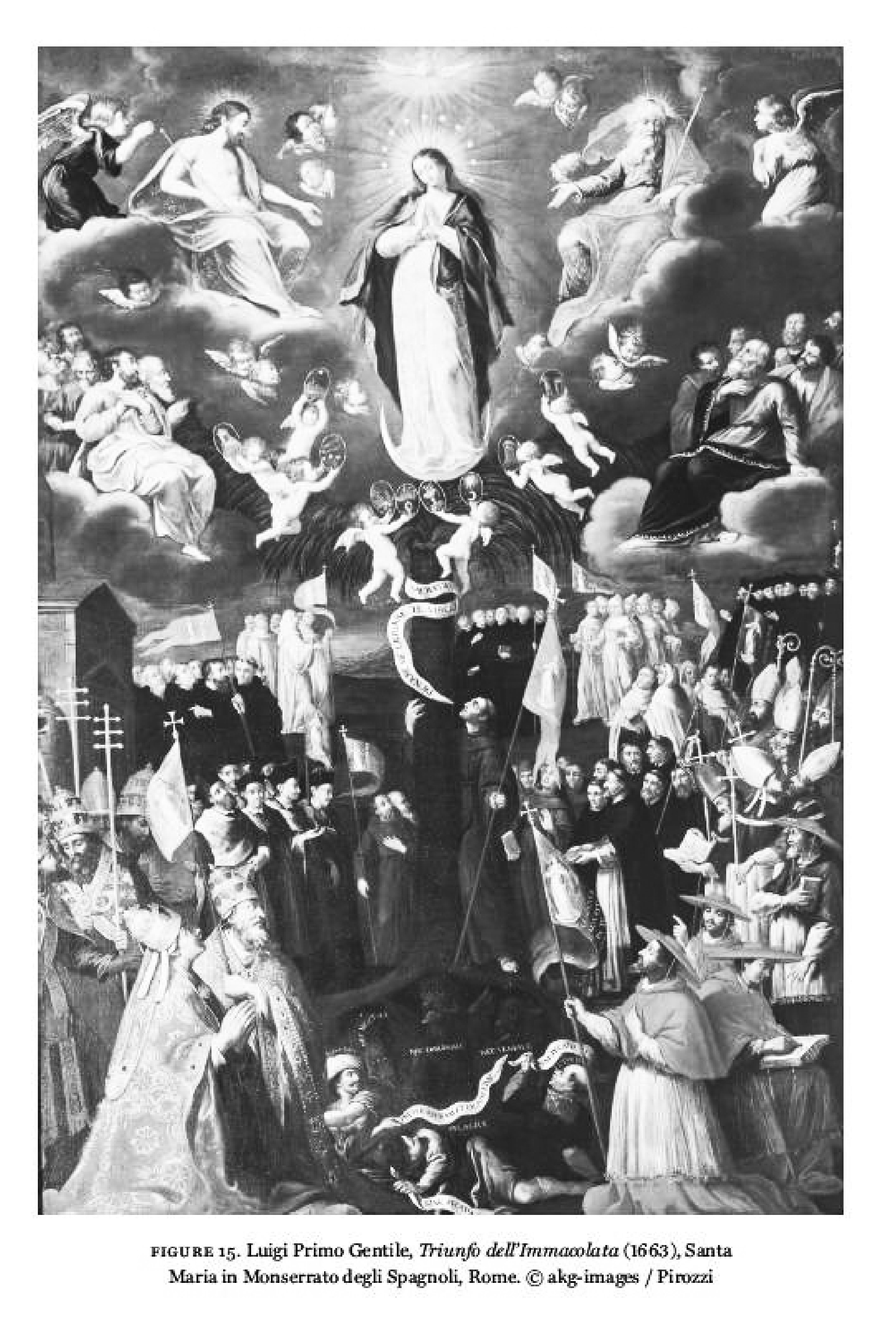

In Europe, the situation was not vastly different. In his book "Faces of Muhammad," John Tolan discusses the Catholic-Protestant conflict and how Catholics equated Protestants with Muhammad. During the 16th century, artists commissioned by the Catholic Church excelled in satirical art. They portrayed "Mahomet" and Martin Luther in their paintings but as heretics and apostates. Despite acknowledging the purity of Mary, the mother of Jesus, the Catholics did not grant them forgiveness. In one of the paintings, they depicted these figures at the depths of the Earth, beneath the feet of faithful Christians who gazed up toward the Virgin.

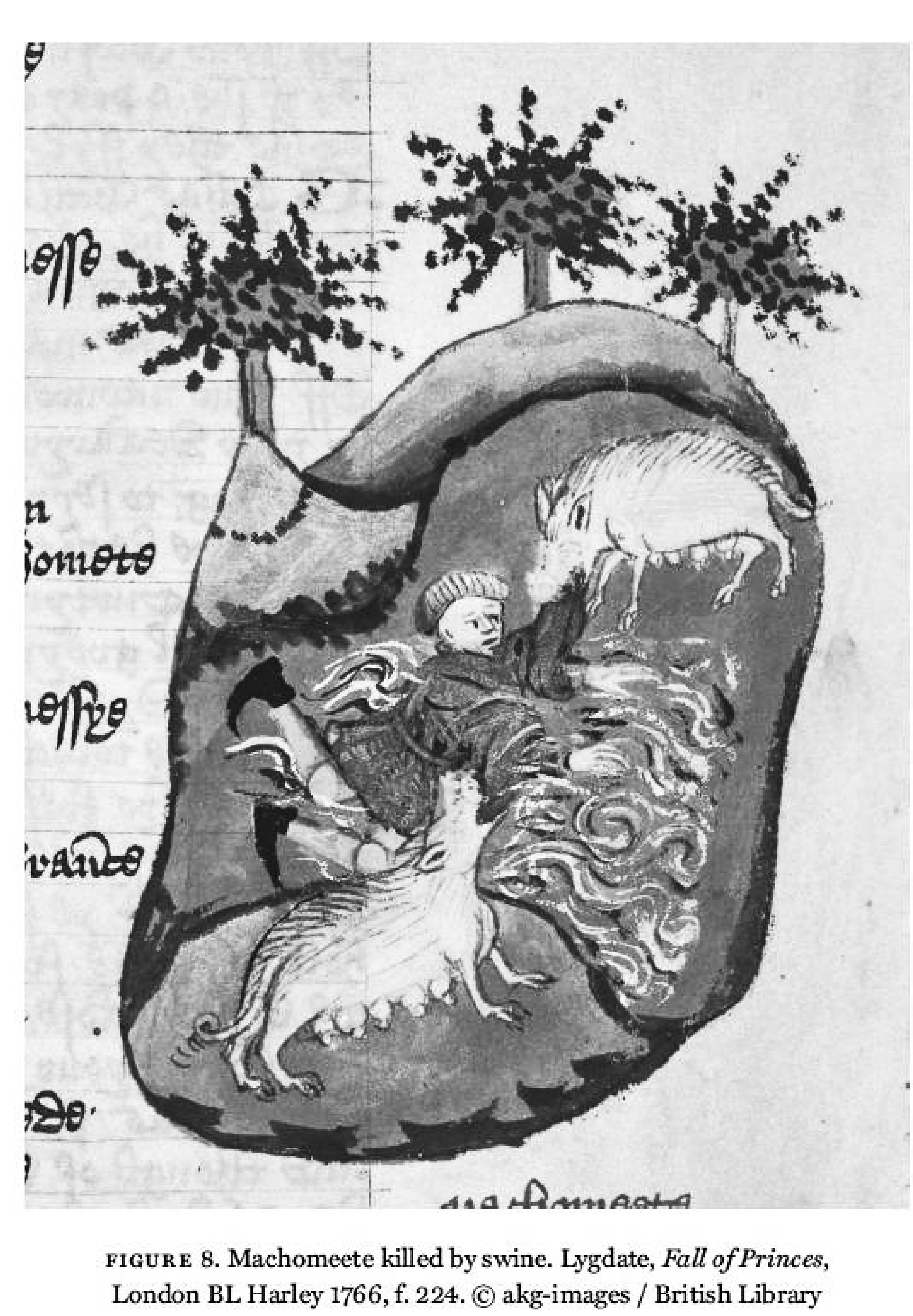

Just as Voltaire erroneously claimed that Muhammad held the moon in his sleeve, these stereotypical depictions extended to the unverified assertions of Church artists that Muhammad died in a drunken stupor and was consumed by pigs, leading to the prohibition of pork consumption among Muslims.

This prompts the question: From where did Europeans derive their knowledge about Islam and the East?

Tolan asserts that these entrenched stereotypes endured robustly and rarely faced opposition, thanks to a politicized form of Orientalism. There were, however, a few exceptions, notably the German Orientalist Abraham Geiger (1810-1874) and his pupil Gustav Weil (1808-1889). They concurred that "Muhammad was not a charlatan but a sincere reformer," a sentiment shared by another Orientalist, Isaac Goldziher (1850-1921). Strikingly, all three were of Jewish descent and admired the urban design of Budapest, Hungary, for its architectural resemblance to the Arab Umayyad style. Regrettably, much of this architectural heritage was demolished by the Nazis, as documented by Tolan.

While the name Mohammad served as a badge of shame for some, others regarded it as a badge of honor. For instance, the Frenchman Victor Hugo described Napoleon Bonaparte by saying, "It is as if Mohammad had come from the West." According to John Tolan's book, Napoleon himself saw his mission as akin to that of a new Muhammad.

While the name Mohammad served as a stigma for some, others regarded it as praise, such as Frenchman Victor Hugo, who quoted Napoleon Bonaparte saying, "It's as if Mohammad had come from the West." According to John Tolan, Napoleon saw himself as a new Mohammad

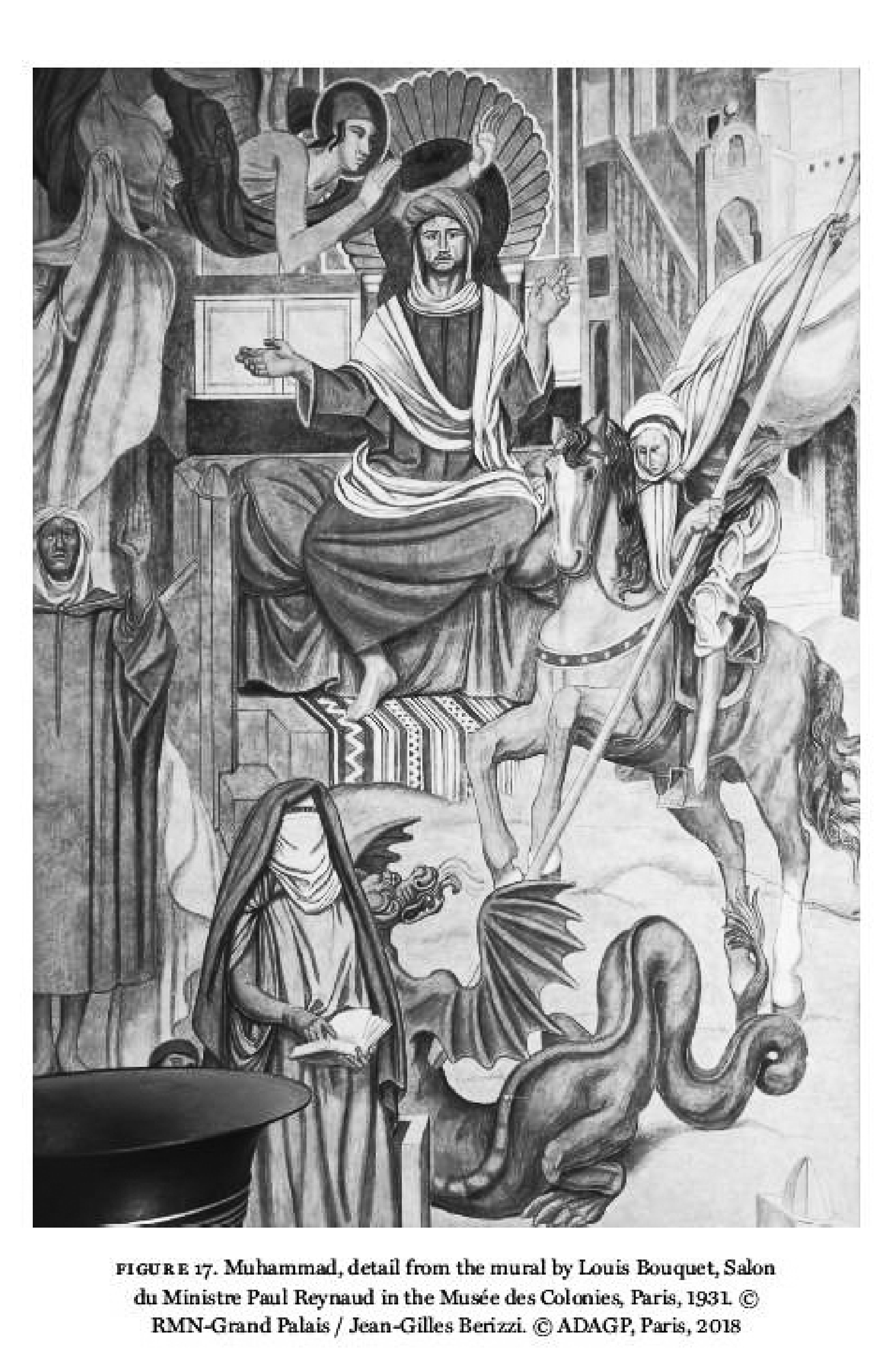

During the 19th century, a handful of impartial voices began to emerge among Orientalists, but they eventually receded in conformity with colonial policies. Among these more balanced perspectives of an artistic nature, there exists a piece of artwork depicting the Arabian Prophet as a human figure enveloped in a sacred aura, with the angel Gabriel whispering in his ear, but this portrayal depicts him as a person of African descent.

Despite occasional glimpses of neutrality, overt bigotry often took center stage, as exemplified in Mark Twain's work, "The Innocents Abroad." In this book, the American author showcased his prejudice against Arabs and Muslims. During his 1867 visit to Palestine, he came across a column in Jerusalem, mistakenly believing that Muslims believed the Prophet Muhammad would serve as a judge and arbiter while sitting upon the column on Judgment Day. Twain said, "I wish he'd judged them from his homeland Mecca, and had not crossed the borders into our Holy Land."

The concluding phrase, "our Holy Land", exposes the bias of some individuals against anything associated with the East. For many centuries, it was not uncommon for Orientalists to depict Christ as a European figure instead of an Eastern one, irrespective of his Palestinian origins. So it is no wonder the image of a fair-skinned, blue-eyed, and blond-haired Jesus became prevalent. For Christ to be tan-skinned, with black eyes and hair, is unacceptable, since to these observers, Christ's sanctity, as perceived by the white man, was reinforced through the West's affiliation to him.

Remarkably, it was the Orientalists themselves who propagated these stereotypes. As Said argues, "what the Orientalist does is to validate the prevailing image of the East in the eyes of his readers; as he has no intention of challenging these firmly rooted beliefs."

Despite these stereotypes and images, there have been several impartial and rational studies conducted at various points in history. Works like Gustave Le Bon's "The Civilization of the Arabs" and John Tolan's yet-to-be-translated book, "Faces of Muhammad," stand as examples. However, on occasion, remnants of medieval-era stereotypes resurface in juvenile acts, such as burning copies of the Quran, creating provocative caricatures of Mohammad (or "Mahomet"), or producing offensive films like "Innocence of Muslims", which faced substantial criticism from Western intellectuals, with Salman Rushdie being among the prominent voices against them.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!