I have this problem. I can’t write on command, I approach it like a chore. It’s always squeezed out of me, or happens as a means of trying to escape doing something else.

It’s been about a month since the Kawkaba show opened at Christies. I wrote something that some people found profound. They asked me to write more, then my friends egged me on. Try as I may, I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I revisited the show in hopes of finding a spark to write. And sure enough, no shortage of ideas. And now, here we are at 3 am, with a few days of this exhibition left and a burning urge to be there every day until the end of the show.

My first trip was a profound one. It unlocked so much and it’s hard to know where to begin and where to end. But perhaps it’s here:

So many years in the city I called home. Not once have I ever visited Christies. And perhaps to no one's surprise. I dwell in green rooms, tour buses and train stations.

Last year in Baghdad I got to visit an exhibition that held some of the finest work by pioneers of the Iraqi Art universe. I spent days in that exhibition alone, hours on end staring into paintings and works by the greats. So much so the curators began to worry and would check in on me. It altered my existence and art practice forever.

In Baghdad the paintings barely had any descriptions, next to each artwork was a small label with the artist's name. Some were dated, some were not. Some had titles, others had serial/lot numbers. Most of these works had been looted or disappeared at some point before having been returned. Two particular paintings commanded my attention as soon as I stepped into the empty gallery, I knew nothing about them. And to be frank, I still don't know a whole lot. It’s been just over a year since I returned from Baghdad. And I just learned the name of one of them.

I spent two hours circling the room that day, photographing paintings and signatures up close. Taking in every detail I could possibly conceive. It was tiled with marble floors if I recall correctly and there was a leak in the corner that a few people were greatly ashamed of. I understood why but it didn’t make me feel any type of way. Those were not the details I was there for.

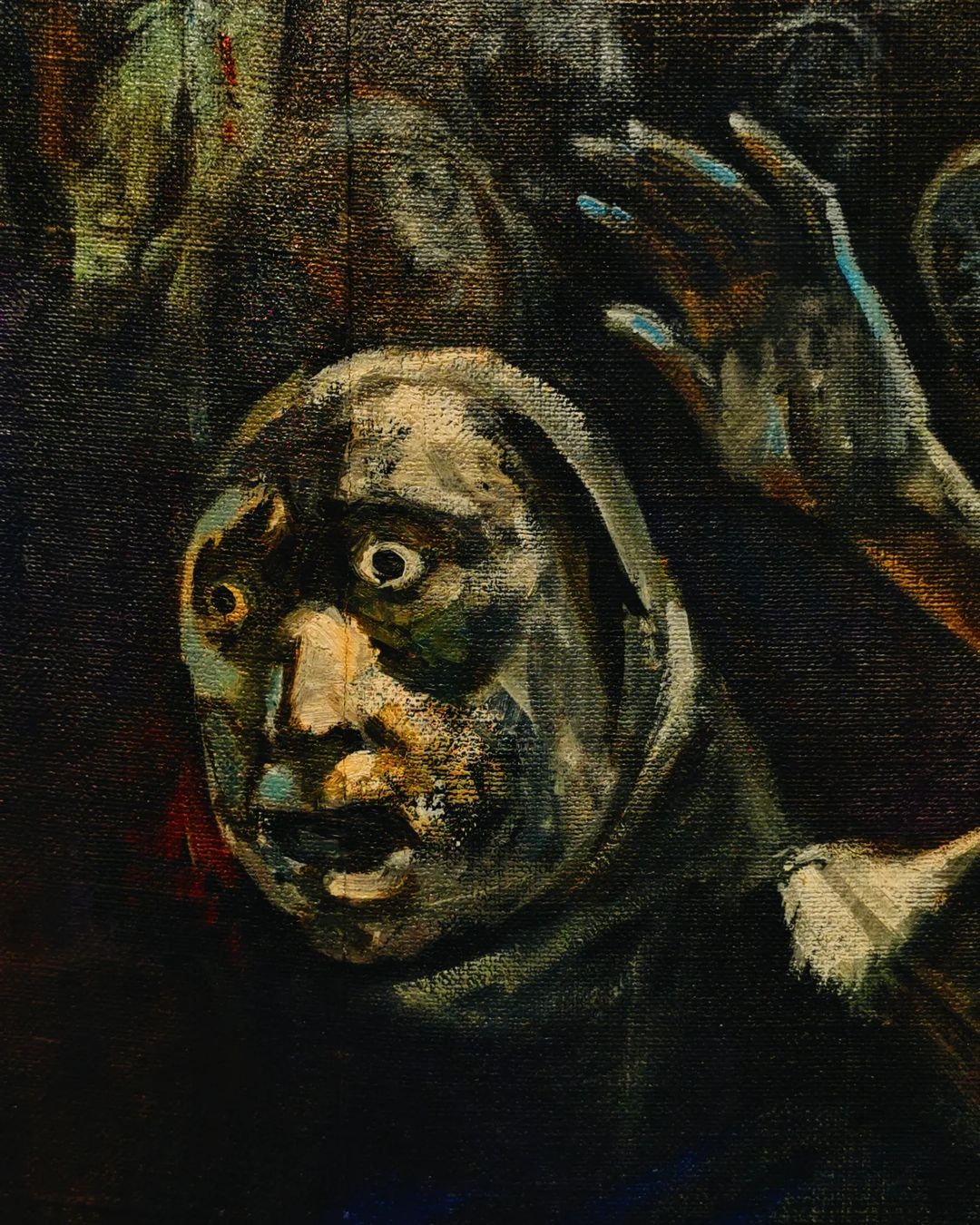

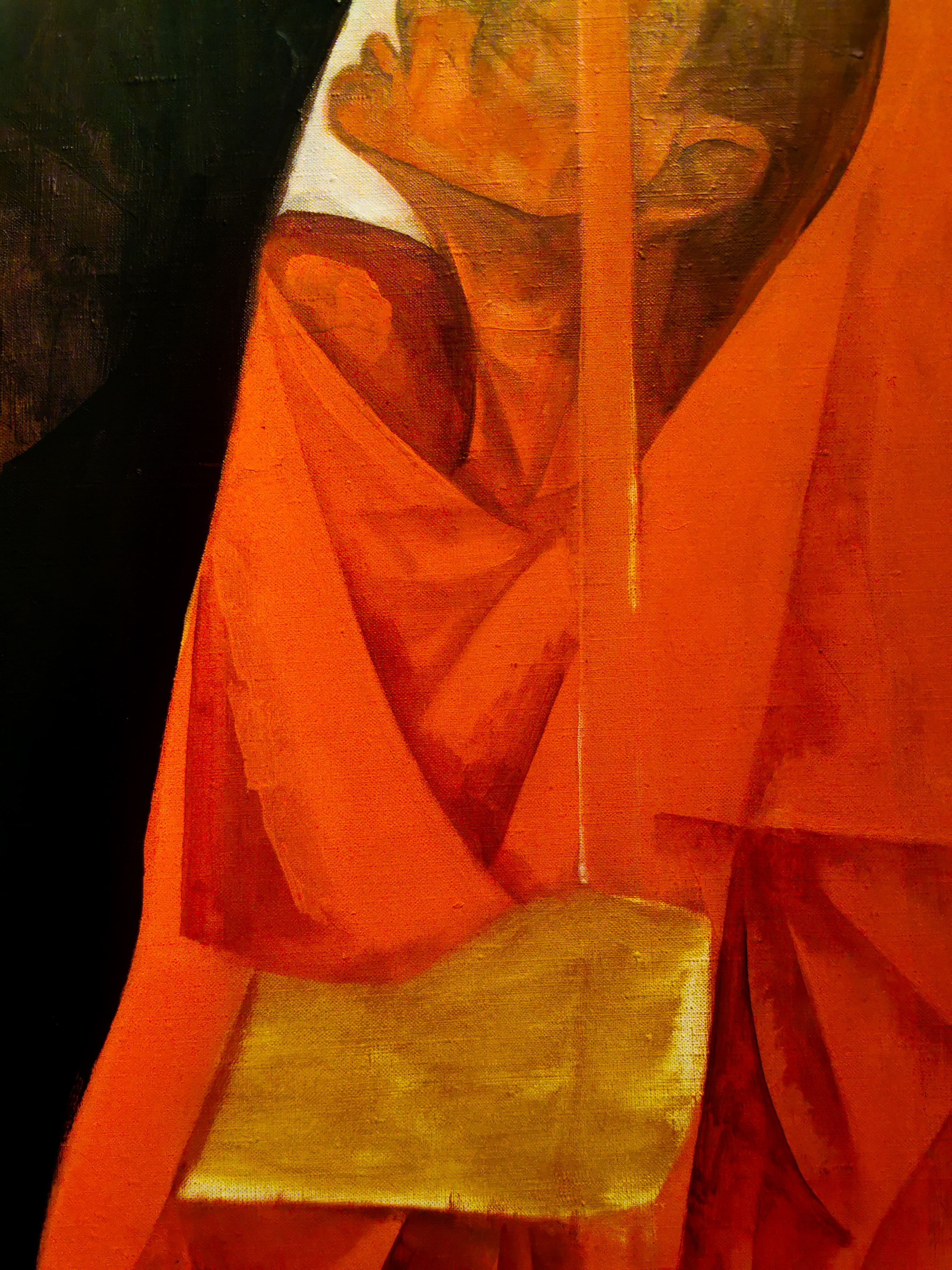

I sat on the floor in front of this painting by Faeq Hassan and time passed. It reeked of something that I couldn’t put my finger on. And perhaps that’s what kept me. It had a haunting allure that I couldn't shake. I wondered what the scene it depicted sounded and smelled like and I was reminded of a conversation I had days prior where a friend describes going home following tragic news. He describes the same event almost 30-40 years apart, where groups of young men in different times but of the same place were rounded up by powers that were. The most vivid part of his descriptions were the sounds, up until I had seen this painting I couldn’t see an image for his description.

His exact words were: “أبد ما أنساها هاللحظة. أمشي بالشوارع و ماكو كل أحد. بس آني و صوت النحيب”.

Translated: I’ll never forget that moment. Walking down the streets and there was not a soul in sight. Just me and the sound of wailing.

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

Faeq Hassan - تل الزعتر

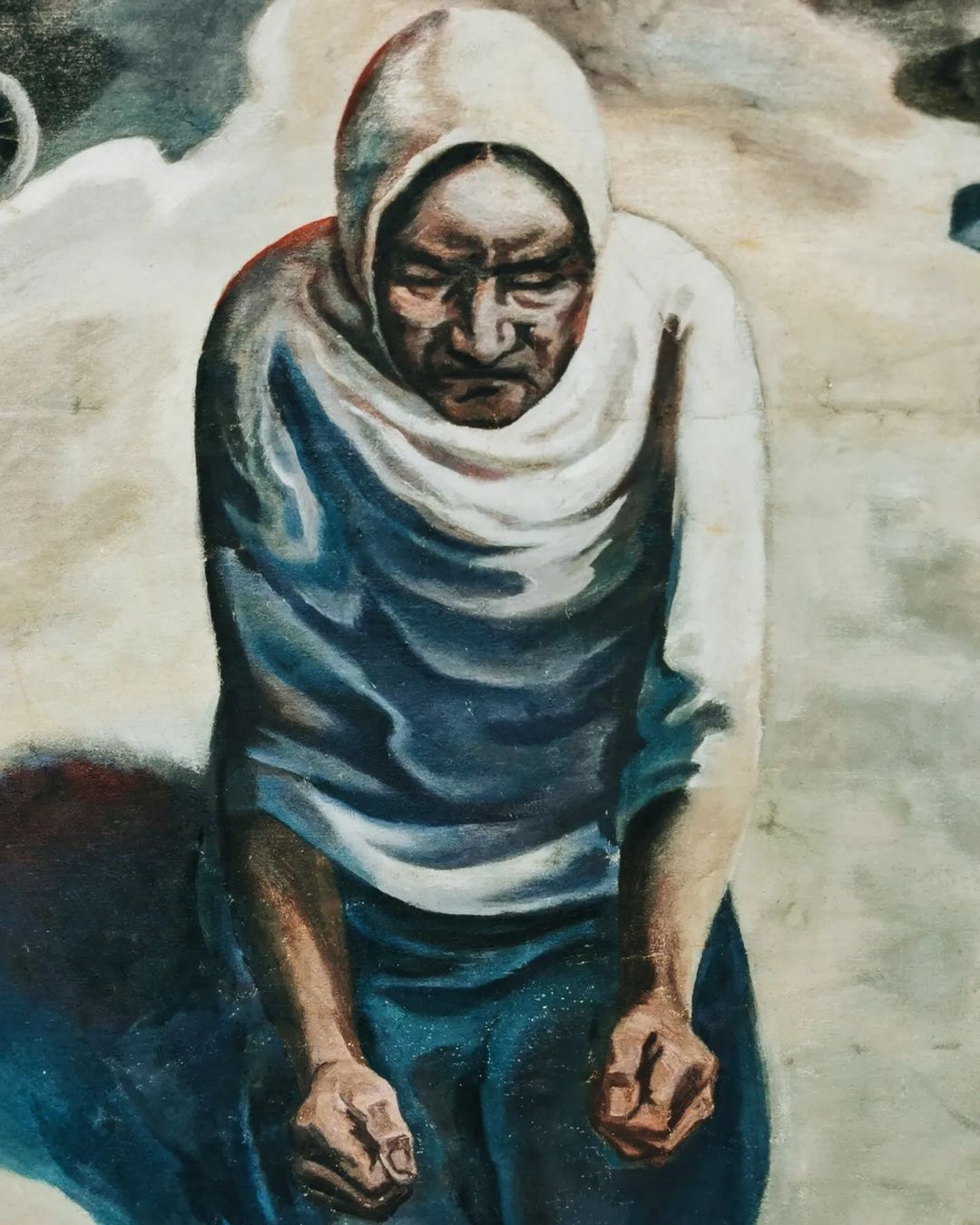

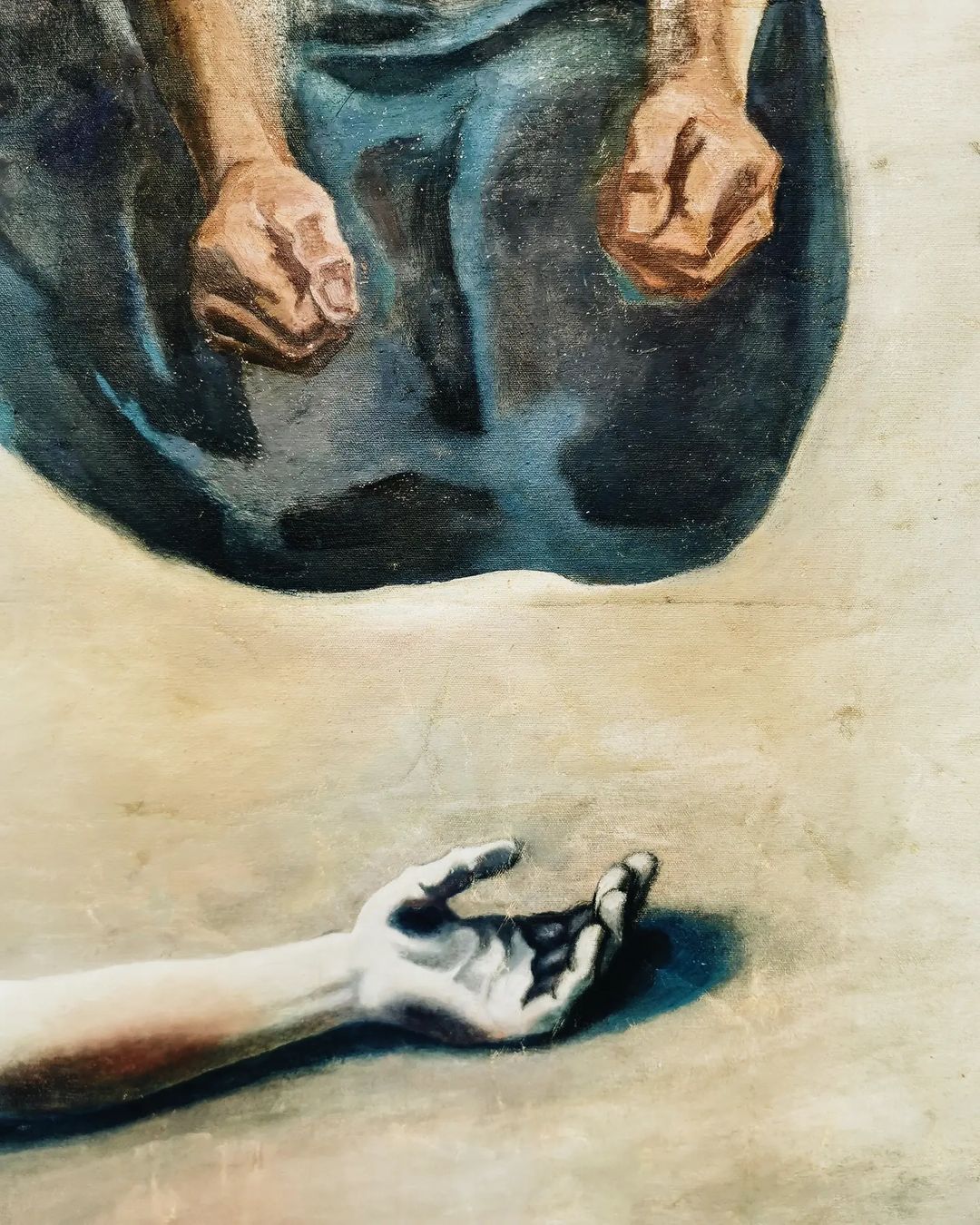

After a while I returned to a Mahoud in the same gallery that made me feel similarly. An old woman surrounded by the ruins of what appeared to be her house, with a hand sticking out from under the rubble. Some more time passes when I’m approached by the only other person in the gallery. An older woman in a burgundy suit, glasses on the tip of her nose who was sat at a desk in the centre, reading.

She stands over my shoulder as i’m sat on the ground and asks me why I like these paintings. “They’re so full of grief,” she says. I don’t really answer with much other than a shrug and an unbreaking eyeline. She takes off her glasses to take a look at me and says “and you’re in all black too, like a funeral”. I take a look at myself and sure enough I am dressed in all black. She puts her glasses back on and says look, if you want you can drop your backpack over there at the desk where i’m sitting. Seeing you carry it for this long is making me tired. We chuckle, I thank her and she retreats back to her desk. The truth is I wasn’t so sure grief is what it is that was overwhelming about those paintings. It was something else.

I buried the experiences from that day deep into my work and process and tried not to ask too many questions of myself. I came to understand that while it’s possible, not everything must be explained in words. Least of all English words. So much about Baghdad cannot be carried by the limitations of this language. And that’s true of its art too. I wish I could tell you this is an article about Kawkaba or that exhibition in Baghdad. But it’s about neither. This is about ideas and experiences that remain incomplete.

I knew when I began to hear of the works that would be on display for Kawkaba that I would have to find my own time again. And visit when footfall was at its lightest. To get my time, as I did in Baghdad. And so I did.

Places like Christies make me feel tense and uncomfortable. Like when you’re followed down an aisle in a shop by a bossman trying to make sure you don’t steal biscuits. Except these biscuits are quite expensive and not for consumption, but the coffee is free.

Part of me is already nervous to be here, Iraq has a chequered history and experience with auction houses. Particularly ones that trade in art and antiquities, but I won’t twist that knife today.

I order a flat white and make my way up the stairs into the first gallery where I’m greeted by the emptiness I was praying for. I start to take it all in, I want to see it all at once but also every piece on its own. I pace from room to room and ditch my friends, I walk into one where I’m greeted by the unmistakable Gateway to the west by Mohammed Ghani Hikmat. I turn to my right and I see a wall adorned with works by Jawad and Naziha Salim. This whole room felt like one of my bookcase shelves swallowing me up and spitting me out. All these works I had hunched over with magnifiers and scanners to get better looks at were all before my…..”SIR YOU CAN'T HAVE COFFEE IN HERE”. -WHAT?!- “NO DRINKS ALLOWED” Why would you serve them free at reception then? “Sir please, you have to leave”.

Downing my coffee to get back to the task at hand probably didn't help the nerves, but between “wasting it is haram” and “I didn’t pay for it anyway” it felt like the best course of action. I took a deep breath, now amped up on coffee and went back in to start again. This time methodically, I had to stop running around from wall to wall to make sure I didn't miss anything.

I sell books sometimes, and there’s something real humbling about standing in front of works by all the names on those book covers. And I felt it in those moments, recognising fragments, connecting dots. But I wasn't ready to be whisked back to Baghdad, in my all black. Sitting on that marble floor staring at grief filled paintings again.

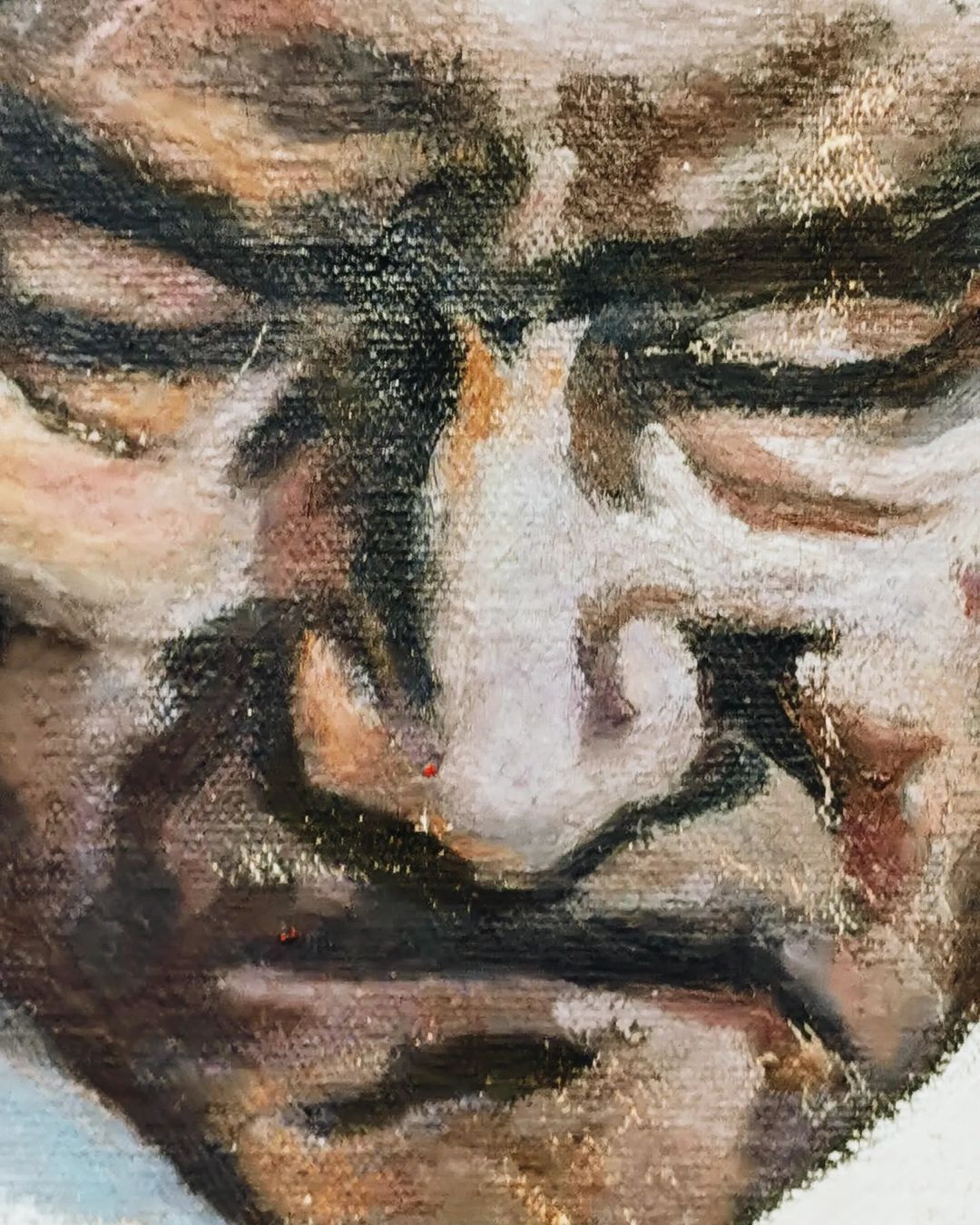

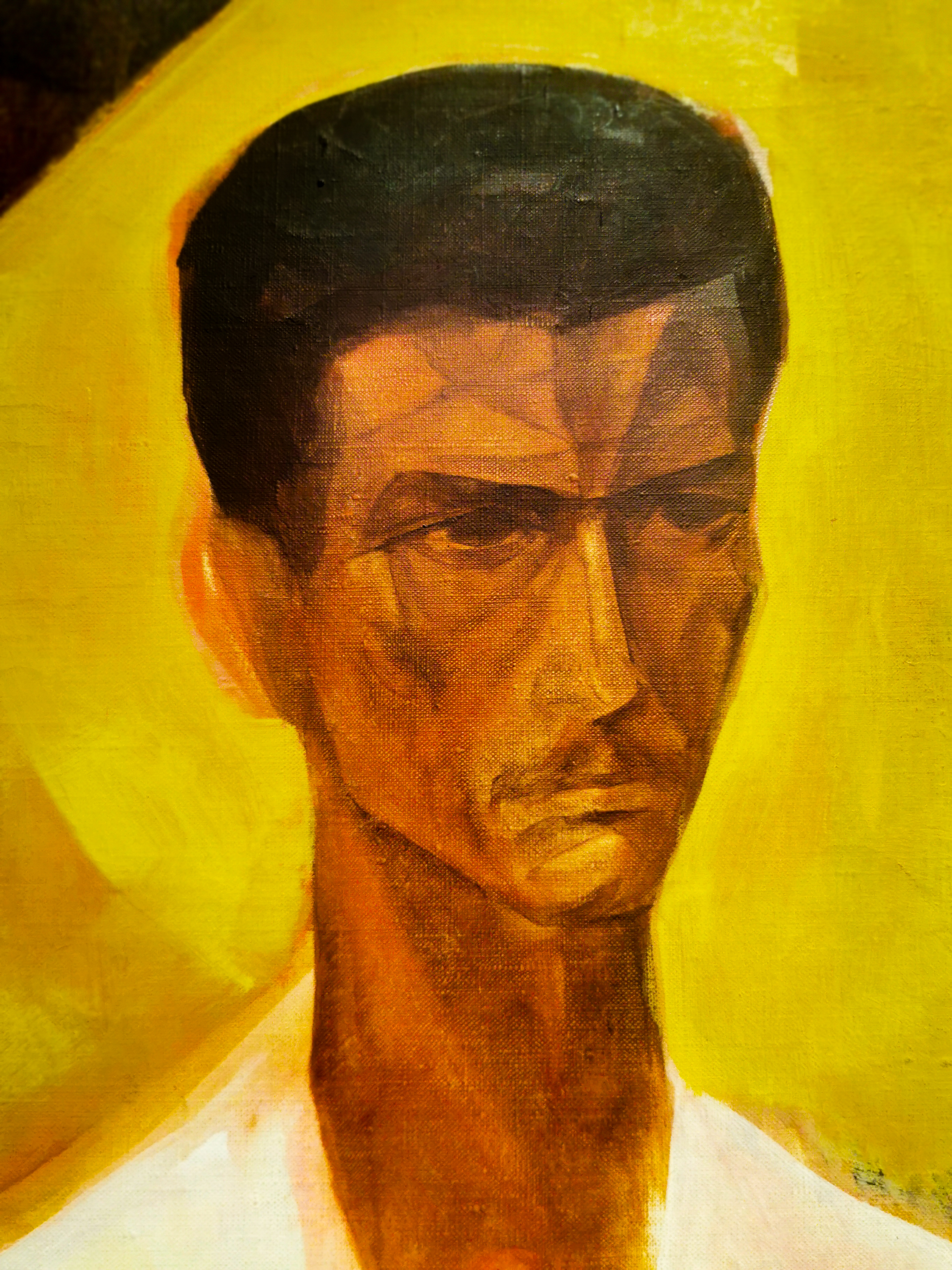

In the second room we’d return to chaos. All my self talk about doing it methodically left the chat and I beelined to this one painting. I told myself it had to be a Faeq Hassan, it has all the hallmarks. I look not for the name next to the painting but into the expressions of all is people. One by one, every face checks out. The expressions, that haunting allure, the composition, the sound of wailing. All of it screamed that painting from Baghdad. After scanning heavily, I look at the label to confirm my suspicion and feel a smug sense of achievement. But I’m wrong. It’s not a Faeq Hassan. In fact, it’s not even a Mahoud.

Now there's a handful of people in the gallery. But I have bigger problems to solve. I put this problem away in my mind a year ago in Baghdad and now it’s back. The echo of that woman asking me why I liked those paintings is ringing in my ears, I look down at myself and yet again I’m sat on the floor, legs crossed, examining a painting and I'm covered in all black.

I loved a lot of the works in the gallery. But this particular piece brought me back. It reopened this well of questions that I quelled. What do all of these paintings have in common. Why am I perceiving this connection that I can’t seem to identify? There’s more to it than the fact that they’re all Iraqi painters. Or that they depict tragedy or grief. That’s all too easy, too surface level. I’ve spent this past month trying to get to the bottom of this question. Perhaps it’s been the crux of why I haven’t been able to write this until now.

On one of my latest visits, I ran into Sultan Al-Qassemi in the Gallery. Luck and my obsession with this painting would see me there just in time for him to give myself and the small crowd gathered around this painting some background on it. While it was informative and good, It didn’t give me my answer. Later Sultan tells me I’m a poet and it strikes something. I leave the exhibition and pull up my pictures from Baghdad, I put them side by side with the ones I’ve just taken in London. And it all falls into place for me. I’ve read these paintings as poetry long before I ever perceived them as Images. So many poets have written plenty in descriptions of Baghdad and Jerusalem, and I often see kindred spirits in the cities' descriptions of themselves and each other. But the connection these paintings had was deeper than that. They described and illustrated death in a way only a poem could.

Death and danger in western art and civilization is often observed and depicted as terrifyingly sudden, within a blink of an eye. Nobody knows what it looks like, dark myths and haunted figures or gory dark ages and blindfolds. It comes unexpected and uninvited. But not here. These artists spent time staring into it’s face and crafting it’s image. You would have to see death, anger and anguish and not run from it, but pace directly towards it to pull off what they did. They would've had to sit through it all in order to create an image so vivid. You would have had to never run.

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

The Hero (Mahmoud Sabry)

Perhaps there is no finer poet than a Palestinian, our kindred spirits to capture in words what Iraqi painters put in images for so long. In conversation with death, Tamim Al Barghouthi writes:

قد رأيناك حتى حفظنا ملامح وجهكَ

عاداتِ أكلكَ

أوقاتَ نومكَ

حالاتِك العصبيةَ

شهواتِ قلبكَ

حتى مواضع ضعفكَ، نعرفها

أيها الموت فاحذرْ

ولا تطمئن لأنك أحصيتنا

نحن يا موت أكثرْ

ونحن هنا،

بعد ستين عاماً من الغزو،

تبقى قناديلنا مسرجةْ

بعد الفي سنةْ

من ذهاب المسيح إلى الثالث الإبتدائي في أرضنا،

قد عرفناك يا موت معرفة تتعبُكْ

أيها الموت نيتنا معلنة

إننا نغلبُكْ

وإن قتلونا هنا أجمعينْ

أيها الموت خف أنت،

نحن هنا، لم نعد خائفين

تميم البرغوثي

Translated:

We have seen you for so long we’ve come to memorise your facial features

Your eating habits

Your bedtimes

Your irate states

Your heart's desires

Even your soft spots, we know them

So death be warned

Do not rest because you have us counted

For we are more

And we are here

After 60 years of battle

Our lanterns remain lit

After 2000 years

Of Jesus attending the third grade on our land

We’ve come to know you oh death, with a familiarity that exhausts you

Oh death, our intentions are declared

We’re defeating you

Even if they killed us here whole.

Oh death, YOU be afraid

We are here, scared no more.

-Tamim Al Barghouti

The whole experience of visiting the exhibition at Christie’s feels odd. It feels happy. It feels painful. It feels as blissful as it is withering. Like visiting a loved one in prison, or boarding school. Glad to see you, sad we're not home.

But home is where we make it. And I’ve encouraged all of my friends in this time to make time. And a home amongst this art whilst it's in town. The collection is magnificent and a testament to the spirit of exiled peoples of all nations.

I had told my friends I was very keen to visit at an early hour to ensure the gallery was empty. And that I would be free of distractions, at least on the first visit. And sure it was. I was deep in concentration taking in this large scale painting, completely alone in this room. Not a whisper. When suddenly my ears pick up a heavy sigh from the corner of the room and the all too familiar "أويلي ع العراق".

I don't feel sorrow, I don’t feel sadness. Nor do I feel pride or a sense of patriotic attachment. For now I just know some things connect. And nothing is finished until we are.

I don't know if we've ever had something this good and this accessible for our art in London. And truth be told, way things are going. I don't know if we ever will again. It’s bitter sweet, and perhaps I'll shroud myself in black for one more visit before our time is up. I hope by now you’ve made time for your visit too.

I know one thing for sure after visiting Kawkaba. This isn’t the first time we’ve existed. As artists, thinkers, creatives, human beings and people forging what feels like new paths in a hostile world. We’ve been here before, and we’ve made it back again. People like us existed back then, and they’ll exist when we’re gone. Be fearless about what you put on a canvas, one day it may be your only remaining truth.

I should still call my grandma.

But before I go, I’d like to leave you with one of my favourite quotes in this universe. Found in a book by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Quoting Jewad Selim.

“Art in Mesopotamia has always been like it’s people, who have been the product of the land and climate. They have never reached decadence and never achieved perfection; for them perfection of craftsmanship has been a limitation on their self expression. Their work has been crude but inventive, has had a vigour and boldness which would not have been possible with a more refined technique. The artist has always been free to express himself, even amid the state art of Assyria, where the true artist speaks through the drama of the wounded beast.”

There's never been a better time for us to take up space.

Iraq Everywhere. Iraq Forever.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!