Falah Salah, 19, is hard to miss if he passes by you on the streets of Basra. With his petite and frail stature, his face bears unmistakable signs of profound weariness, making him appear much older than he actually is.

He would forcefully strike his chest and candidly tell you, "It's the crystal meth drug that has done this to me." After a brief pause to gauge your reaction, he would add with a touch of pride, "But I've conquered my addiction."

Falah lives in a dilapidated house with his parents and four siblings in Basra's Al-Jumhuriya neighborhood in southern Iraq. Due to challenging financial circumstances, Falah's educational aspirations halted at the third year of middle school. His family simply couldn't afford the expenses associated with his education and that of his siblings. So, instead of attending school, his circumstances compelled him to take to the streets as a street vendor. This marked the beginning of the story of his descent into drug abuse in 2019.

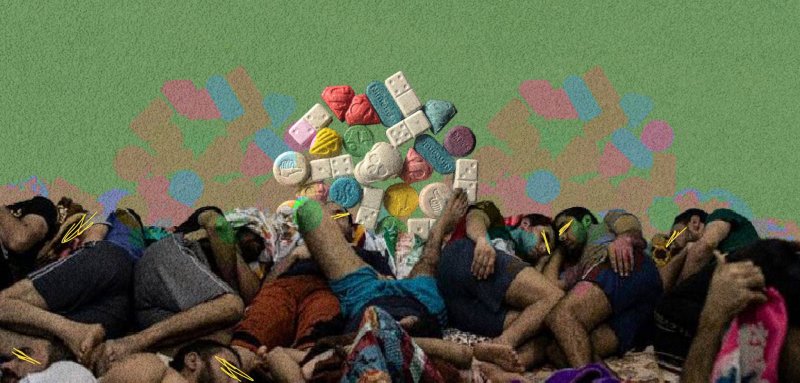

He explains that he became involved with a group of teenagers, among whom was an individual who freely distributed crystal meth among them. He described this drug as a "liquid substance placed in a glass tube, is heated, and then inhaled as smoke. It is the most prevalent drug in Basra." Subsequently, they began buying it from him, and over time, Salah became addicted. "I used it for over two years, and my health deteriorated significantly. Fortunately, my family intervened, and I was admitted to a rehabilitation center. It has been five months since I last consumed any substance, and I am determined never to return to it."

Although Falah still roams the streets, he now works as a marketing representative for a company that sells drinking water filtration systems. He wishes he had the means to help other drug addicts, just like he had received the help he needed and was able to rebuild his life, as he puts it.

"In Basra, many licensed bars and nightclubs were already closed down, even before the law came into effect after a decision by the provincial council. So many young people turned to drugs because obtaining them became easier than acquiring alcohol"

Based on his experience, Falah believes that drugs are spreading very quickly, due to the alcohol ban law that came into effect in March 2023. He says, "In Basra, there were many licensed bars and nightclubs that were closed down, even before the law came into effect. This closure resulted from a decision by the provincial council. Consequently, many young people turned to drugs and other forms of narcotics because obtaining them became easier than acquiring alcohol."

To illustrate the ease of drug distribution in Basra, Falah provides an example, "Dealers would park their cars on the side of the road, waiting for customers. They would provide the substance and collect payment before continuing on their way, simple as that."

His face tightens and then relaxes several times, and he brushes his hand across his forehead and confesses, "This is also due to the damned crystal drug." He goes on to highlight another factor, saying, "The prices of pills are lower than those of alcohol, especially now, since the availability of alcohol has become limited and can only be purchased secretly, much like drugs."

Drawing from his personal experience, Falah also reveals that many young people used to consume alcoholic beverages in the streets and public parks. However, after being pursued by the police, they formed what they called "dens" or hideouts. These dens are houses rented by groups of young people in random residential areas and slums, where they would indulge in both alcohol and drugs.

According to Falah, the number of these hideouts has increased, and they have become safe spaces for drug dealers in Basra. They basically serve as learning grounds for young individuals to become addicts, as he explains.

"Each person brings out whatever they have and shares it with others. And this is where the dealer showcases his merchandise," he says, then adds, "There is a large number of drug dealers in Basra, and they can be found almost anywhere teenagers are present, even in schools. Their operation functions in a hierarchical manner, with major traders at the top, followed by lower-level dealers. Each trader employs a group of distributors who freely spread and distribute drugs throughout the city."

The government's shortcomings

A police officer, holding the rank of major in the Basra Narcotics Division, corroborates Falah's account and expresses his regret over the numerous obstacles faced by the province's anti-drug apparatus. He laments, "Drug traffickers and dealers are constantly developing their methods, while we lack the necessary resources. The developmental courses and training for our personnel falls short of the required standard, and the equipment that would facilitate our arduous tasks in combating this perilous menace is generally inadequate. Additionally, border surveillance is lax, with a lack of thermal cameras or observation towers to cover the areas through which drugs are smuggled, such as Al-Faw, Abu Al-Khaseeb, and Al-Seeba."

The police officer also underscores the scarcity of rehabilitation facilities in Basra. Currently, there is only one center with a capacity of no more than 50 beds. He notes, "Meanwhile, the number of drug users languishing in prisons surpasses four thousand."

The closure of establishments selling alcoholic beverages has contributed to a surge in drug use and addiction "due to dealers targeting the youth. While consuming alcohol is generally discouraged, it poses a lesser risk and can be controlled, unlike drugs"

The officer admits that the closure of establishments selling alcoholic beverages and nightclubs has contributed to a surge in drug use and addiction. He explains, "This is primarily because dealers have found a thriving market, preying on vulnerable young people and enticing them to consume these toxins. While consuming alcohol is generally discouraged and stigmatized, it poses a lesser risk in terms of addiction and can be controlled, unlike drugs."

In 2017, Iraq enacted Law No. 50 to combat drugs and psychotropic substances. According to Article 28 of the law, individuals involved in "managing, preparing, or facilitating places for drug or psychotropic substance use face penalties including life or temporary imprisonment and fines ranging from 10 to 30 million dinars."

Article 32 of the law imposes prison terms of "at least one year and up to three years, accompanied by fines ranging from five to ten million dinars, on those engaged in drug importation, production, manufacturing, possession, acquisition, or purchase of drugs or plants used in drug production or psychotropic substances, or their acquisition for personal use."

Furthermore, the law mandates that drug addicts or users of psychotropic substances be admitted to specialized healthcare institutions. It also requires individuals found to have used drugs to seek psychological counseling to aid them in overcoming addiction.

According to a medical source in Basra, the only addiction recovery center in the province is not sufficient in meeting the significant number of addicts in the region. Despite this, the center has accommodated addicts from the Nasiriyah and Maysan governorates, which lack their own treatment facilities.

The center in Basra currently has a capacity of only 44 beds, with 23 allocated for men and the remainder for women. However, during the first half of this year, it received over a thousand cases involving both men and women, with an average stay of three weeks per person.

Previously, Dr. Ameen al-Zamel, the director of the Addiction Department at the Basra health department, stated that 419 drug addicts in Basra, whose ages ranged from 16 to 35 years old, received treatment in 2021. He also acknowledged the center's inability to accommodate the growing number of addicts and called on the Health Directorate to expand the center to house at least 400 individuals.

Groups and entities benefiting from the drug epidemic

In Basra, there are individuals who hold powerful political parties and militias widespread there accountable for the drug epidemic. They claim that these entities have been working a long time on banning alcohol in order to promote and distribute drugs, thus making significant financial gains.

Some individuals in Basra hold powerful political parties and militias there accountable for the drug epidemic, saying these entities have been working a long time on banning alcohol in order to promote and distribute drugs, and make major financial gains

Ali Al-Abbadi, the head of the Iraq Center for Human Rights in Basra, sheds light on this matter, stating, "Based on our monitoring and dialogue sessions conducted as part of the drug file in the province, and information received from our confidential sources within the security establishment, there is significant interference from influential figures in the political arena, as well as others who wield influence in armed factions that facilitate the smuggling of drugs into Basra through border crossings and aiding their circulation."

Al-Abadi accuses political blocs in Basra of direct or indirect involvement in drug trafficking and smuggling. He explains, "Regarding those involved indirectly, they are complicit through their silence, failure to enact the necessary laws, and exerting pressure on the central government to combat this phenomenon."

Furthermore, he also accuses government institutions of failing to reduce the drug problem and highlights their inadequacies in addressing the escalating drug problem in Basra. He emphasizes that the roles played by civil society organizations, human rights centers, civil activists, and volunteer groups in combating the issue far outweigh the role and contributions of these state institutions.

He calls for a nationwide campaign to reduce the dangers of drugs, as he sees them as more deadly and lethal to society than terrorist groups. He urges, "Just as efforts have been dedicated to combating terrorism, we should mobilize our efforts to the war against drugs."

Researcher and writer Ghazwan Kazem Mukhlis presents what he believes to be corroborating evidence supporting Ali Al-Abadi's statements. He states that Basra was once known for its vibrant nightlife and establishments that sold alcohol in certain areas, particularly in the Al-Ashar district, specifically on Al-Watan Street, which was a popular destination for young people from Basra and foreign tourists. However, "the allure of this street began to fade, and nightclubs gradually closed their doors over the past decade due to militia harassment driven by extortion and religious extremism."

He indicates that the prohibition of alcohol in Basra did not coincide with the enactment of the alcohol ban law in 2023 but occurred much earlier. Mukhlis recounts an incident in March 2010 when a hand grenade was thrown into a lounge serving alcoholic beverages in Umm Al-Broom Square, located in the Al-Ashar district. No injuries were reported. Shortly thereafter, an alcohol-selling shop on Al-Watan Street was targeted by an explosive device, "In this way, the militias threatened alcohol vendors in Basra and coerced them into shutting down their businesses and nightclubs."

According to numerous testimonies that Mukhlis gathered from affected alcohol vendors during that period, the primary motive behind these attacks was extortion. Armed groups were targeting them to extort a share of the profits in exchange for protection and to not be targeted.

Additionally, there were religious extremist groups associated with Islamic parties advocating for the closure of nightclubs and the prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages in Basra. These groups carried out their actions openly, within full view of the security forces and local government, leading Mukhlis to describe it as "official complicity with armed groups."

Furthermore, the Basra Provincial Council was the first to issue a local legislation to ban alcohol. "The resolution was voted on on the second of August 2008, and imposed a fine of five million Iraqi dinars on anyone involved in the production, import, sale, or consumption of alcohol in public places. The decision overlooked alcohol vendors from the Christian community, but then the local government did not renew their business licenses."

The main driving force behind the vote and issuance of this resolution within the Basra Provincial Council was the Islamic Dawa Party, which had majority representation in Basra's council, along with the Islamic Virtue Party.

Recovery before it's too late

Abdullah Jassem, a 19-year-old from Hayaniya in Basra, comes from a poor family residing in slums. With seven siblings, two older and four younger, Abdullah's father works as a municipal employee, but his meager salary falls short of supporting the family's needs. Consequently, Abdullah abandoned his studies before completing the first year of middle school and did various jobs to earn a daily wage, such as construction work and carrying goods in the local markets. Due to being acquainted with young men involved in drug use led him down the path of addiction. He found himself working solely to fund his drug habit instead of assisting his impoverished family.

Jassem recalls his first encounter with crystal meth. One day, his friends invited him to a 'den', an abandoned, unfurnished house in western Basra, serving as a gathering place for consuming alcohol, indulging in drugs, and dismantling stolen motorcycles

Jassem distinctly recalls his first encounter with crystal meth. One day, his friends invited him to a den, an abandoned, unfurnished house located in the Hayaniya neighborhood of western Basra. This hideout served as a gathering place for consuming alcohol, indulging in drugs, and dismantling stolen motorcycles at night.

At the center of these gatherings was a 27-year-old named Mujtaba. Abdullah recounts. "He was responsible for providing drugs to the youth there. During my first visit, after I was invited by a friend, I reluctantly acquired a bottle of liquor, intending to only drink a little and then leave. However, Mujtaba persistently urged me to stay and offered me crystal meth. Everyone was looking at me, so I felt compelled to do so. I accepted it and consumed the drug, and that was the onset of my addiction."

Soon after succumbing to drug addiction, Abdullah's physical and mental health rapidly deteriorated. "My entire body would tremble nonstop, and I lived in a perpetual state of anxiety, fear, and tension. I reached a point where I was prepared to harm others or even kill myself. I also resorted to theft, partaking in the theft of motorcycles with my friends, dismantling them, and using the proceeds to fuel my drug addiction."

At one point, some even asked him to work as a drug dealer, and roam the dens to distribute pills and crystal meth, but he refused. Fortunately, he is very grateful to some of his loyal friends who helped him break free from addiction more than a year and a half ago, specifically in early 2022. Now, he actively contributes to a volunteer team dedicated to combating drug abuse in Basra.

Drugs, an imminent danger

Ammar Sarhan, the head of the Basryetha Organization for Federal Culture, highlights that Basra province holds the title of having the highest number of drug addicts and users in Iraq. This can be attributed to its strategic location, bordering several countries, which has turned it into a major transit point for drug trafficking. Sarhan further emphasizes the deep-rooted corruption within the security establishment, creating an enabling environment for drug traders and distributors. Moreover, the absence of nightclubs and bars where alcoholic beverages are sold has driven the youth towards drugs, which he deems to be a more perilous and destructive threat to society than alcohol.

Zainab Hussein, a civic activist, raises alarm bells regarding the exploitation of schools as hubs for drug distribution. She recounts a personal incident involving a 13-year-old girl who became ensnared in the web of drugs. Through online platforms, she encountered a young man who manipulated her into peddling drugs among her middle school classmates, enticed by financial gain. Zainab explains, "The young girl naively agreed, unaware of the grave risks involved. She had only her elderly grandmother as a caretaker, as her parents were divorced and had remarried."

When the school administration uncovered the situation, they collaborated with the community police to handle it delicately, ensuring the girl's avoidance of arrest or legal repercussions, thereby allowing her to continue her education. In exchange, she cooperated with authorities to identify the young man responsible for supplying her with drugs.

Zainab expresses her astonishment at the audacity of drug dealers and promoters infiltrating girls' schools for drug dissemination and enlisting unsuspecting students in these illicit activities. She questions, "How are they allowed to do this? How is such behavior allowed to persist? Where are the precautionary measures?"

Ali Manha, another civic activist hailing from Shatt al-Arab in Basra, acknowledges the widespread drug problem in Iraq, particularly in southern cities, with Basra taking the lead. He emphasizes the urgent need for proactive intervention from various governmental institutions to identify the underlying causes, transparently disclose comprehensive statistics, and devise effective strategies to combat the issue. He warns, "Otherwise, Iraqi society is on a perilous path towards disintegration, given the immense harm inflicted by drugs, especially among the impressionable young population."

Manha's viewpoint resonates with others we encountered while preparing this report. He asserts, "The closure of alcohol shops and nightclubs has undeniably contributed to the proliferation of drug-related issues. This concern is compounded by the high unemployment rates and the absence of cultural and educational institutions that play a crucial role in educating and empowering young individuals."

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!