Not on the margins

Not on the margins

This report comes as part of the "Not on the Margins" project, which sheds light on freedoms, and sexual and reproductive health and rights in Lebanon

It’s Pride Month. As Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Intersex, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQIA+) individuals around the world celebrate the historical progress—and future—of the LGBTQIA+ community, many LGBTQIA+ individuals in Arabic-speaking countries continue to face widespread institutional, structural, social, and familial discrimination and exclusion on the basis of sexuality and gender identity.

The legal framework: A facilitator of violations

These practices are particularly apparent in Lebanon. Since 1943, Article 534 of Lebanon’s Penal Code has explicitly outlawed “unnatural” sex, or “any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature”—a fuzzy definition that authorities have used to criminalize LGBTQIA+ people (and considered by some to be a relic of French colonialism). Other articles of Lebanon’s penal code—such as Articles 521, 531, 532, and 533—explicitly and implicitly seek to control same-sex relations and how gender non-conforming and non-normative individuals identify through the control of morality and public decency.

In addition, no other Lebanese law or legal framework mentions LGBTQIA+ people or provides any sort of protection from gender- or sexuality-based discrimination. Critically, this shaky legal status of LGBTQIA+ individuals in Lebanon complicates their ability to easily access qualitative sexual and reproductive healthcare, as it paves the way for various forms of marginalization and discrimination by healthcare providers.

What makes sexual rights more particular for the LGBTQIA+ community?

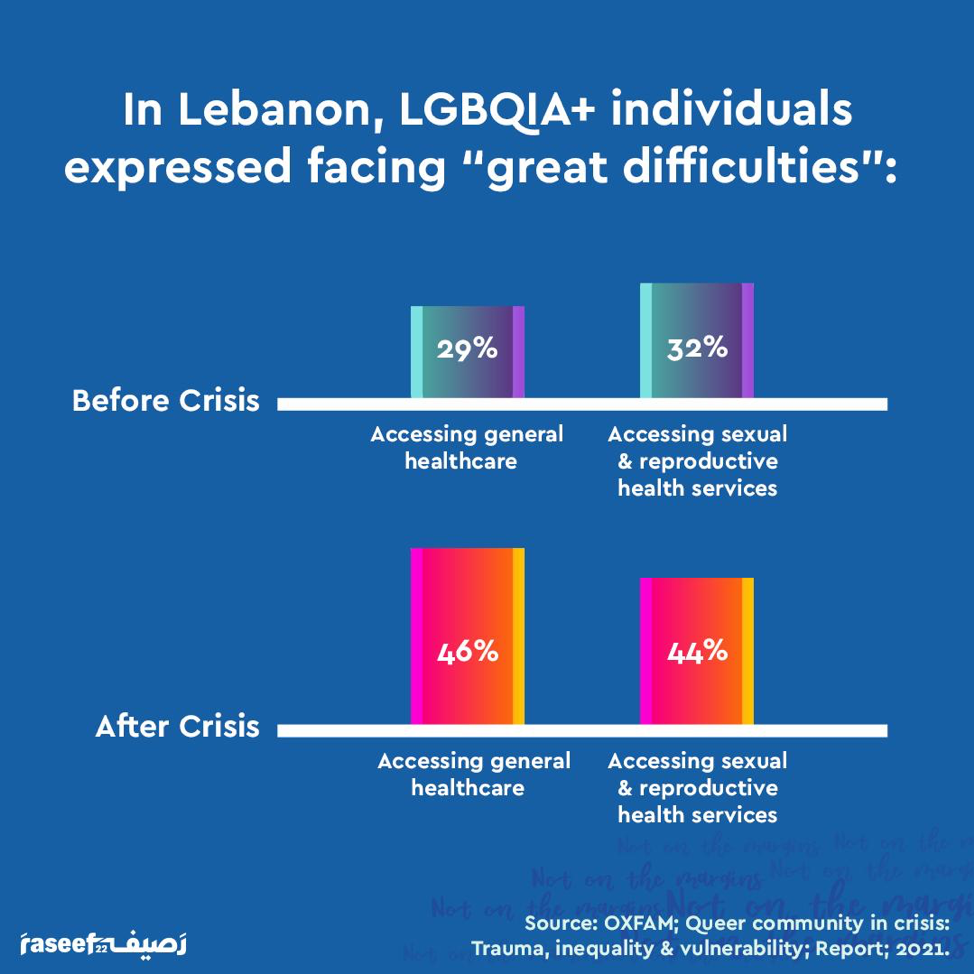

Queer people in Lebanon face a higher risk than cisgender and straight individuals of encountering barriers to equitable healthcare, having less communal support than their peers, and experiencing social stigma and prejudice. A survey conducted by Oxfam in 2021 highlighted that many LGBTQIA+ individuals in Lebanon are reporting decreased access to general and sexual and reproductive health services, in part due to Lebanon’s ongoing economic crisis, former COVID-19 restrictions, and the aftermath of the Beirut port blast.

According to the 2021 report, 46% of queer people in Lebanon said they faced “great difficulties” accessing general healthcare compared to 29% saying so before the crises, and 44% reported “great difficulties” accessing sexual and reproductive health services, compared to 32% before. Queer people in Lebanon also lack adequate numbers of healthcare professionals who are experts in LGBTQIA+ health and healthcare facilities providing safe healthcare environments for such people.

Constituting an increasingly worrisome mental health crisis, approximately 75% of those Oxfam surveyed said their mental health was “negatively impacted” by the crises facing Lebanon, and the other 25% said they were “somewhat negatively impacted.” Oxfam found that Lebanese queer people overwhelmingly faced challenges to their psychological well-being, and 44% of survey respondents said mental health services were “very difficult to access” or “not accessible at all.”

LGBTQIA+ report, 2021 (Source: Oxfam)

LGBTQIA+ report, 2021 (Source: Oxfam)

LGBTQIA+ individuals in Lebanon also face routine harassment and human rights violations—a trend that appears to be increasing. In 2021 alone, for example, the Beirut-based LGBTQIA+ rights organization Helem processed over 4,000 incidents of humanitarian needs, human rights risks/violations, and violence for LGBTQIA+ individuals in Lebanon, up 667% from 2019. Refugee queer populations in Lebanon are especially vulnerable to sexual violence and tend to have a greater prevalence of mental health illnesses compared to Lebanese citizens.

Simultaneously, Lebanon’s economic crisis has hit its queer community especially hard. LGBTQIA+ Lebanese nationals and refugees were unemployed at nearly twice the national average across Lebanon after the Beirut port blast and during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Oxfam’s report, unemployment levels within the LGBTQIA+ community reached about 79% that year, and two-thirds of respondents had no income. LGBTQIA+ people face a series of discriminatory labor practices, including biased recruitment, no legal work guarantees, a lack of equity in pay, abusive or nonexistent work contracts, and unsafe working conditions, exasperating their ability to make ends meet, access healthcare services, and consequently live healthy lives.

To combat these realities, multiple Lebanese civil society organizations are fighting to change the difficult legal and societal status LGBTQIA+ people face in the country. In this article, Raseef22 conducted interviews with three such organizations to better understand the institutionalized homophobia and challenges the LGBTQA+ community faces in accessing sexual and reproductive healthcare. The article also aims to highlight some of the relevant resources currently available to them.

Addressing a lack of services head-on (Nadia Badran, SIDC)

We first spoke with Nadia Badran, the executive director of the Society for Inclusion and Development (SIDC) in Lebanon. SIDC is a Beirut-based organization that was established in 1991 and provides Lebanese people with harm reduction, mental, sexual, and reproductive health services. A fully staffed healthcare provider, SIDC provides various physical healthcare services to the LGBTQIA+ community across different modalities, including HIV/AIDS counseling, treatment for drug users, STI/STD services and treatment, lab tests, HIV partner notification, vaccines, and medication distribution (such as PrEP for gay men). SIDC also offers mental health support for different clients. In our conversation, Nadia stressed that most LGBTQIA+ youth who SIDC works with experience high levels of stress, anxiety, or even suicidal thoughts, and sometimes resort to drugs.

Facing discrimination and criminalization for who they are, young queer people in Lebanon encounter social aggression and a lack of acceptance in their communities—a situation worsened by the helpless economic crisis in the country.

This, Nadia noted, has to do with a societal lack of acceptance for LGBTQIA+ individuals. Facing discrimination and criminalization for who they are, young queer individuals often encounter social aggression and a general lack of acceptance in their communities—a situation worsened by the seemingly helpless economic crisis in the country. Gay men and trans people, for instance, often face stigma from colleagues, family members, law enforcement officers, and healthcare providers related to stereotypes related to their appearance. Many environments “do not accept commonly associated appearances with the community,” which invites bullying and, at times, job termination. Moreover, gay men face heavy stigmatization due to a problematic association between them and HIV, leading many workplaces to be likely to fire HIV-positive individuals due to a lack of legal workplace protections. To help fight this, SIDC keeps HIV and HIV-related healthcare records entirely confidential and avoids asking for the names of patients.

In addition to offering invaluable physical and mental healthcare services to the LGBTQIA+ community, SIDC documents workplace violations and social stigma to engage—and educate—the public and employers. In an effort to decrease general stigmas associated with queer individuals, SIDC trains various members of Lebanon’s community to improve how they treat LGBTQIA+ people. SIDC trains healthcare providers to better understand LGBTQIA+ health and positively interact with queer individuals, encourages acceptance and tolerance with religious figures and media professionals, and works with police to help them learn how to better deal with queer individuals in detention centers. SIDC also engages in communications and advocacy campaigns, negotiates with workplaces, and actively tries to work with Lebanon’s communities to better the situation for Lebanese LGBTQIA+ people.

SIDC, LebMASH and Helem are three NGOs fighting to change the difficult legal and societal status LGBTQIA+ people face in Lebanon. Together they support, lead, and create the right environment for the LGBTQIA+ liberation movement to succeed in MENA.

“With education, behavior can be changed.” (Zavi Lakissian, LebMASH)

“We need to be louder, we need to speak up about the issues the LGBTQIA+ community is facing [...] People have to start listening. Things must change.”

That was Zavi Lakissian, the director of LebMASH, a group of doctors, clinical educators, and healthcare professionals in Lebanon working toward health equity, specifically for the LGBTQIA+ community. Unlike SIDC, LebMASH does not yet provide direct healthcare services. Instead, it occupies a unique niche in providing capacity building, training, and awareness campaigns to healthcare professionals to ensure they know how to provide inclusive and affirming healthcare. Often collaborating with other organizations and working all over Lebanon, LebMASH aims to fill the gap in educating all types of healthcare providers on providing LGBTQIA+ individuals with necessary services, as such information is not normally taught or available to them.

The training LebMASH provides sensitizes trainees to basic vernacular and terms relating to LGBTQIA+ healthcare to provide a baseline understanding of important concepts, including the physical, clinical, and mental health aspects of inclusive care. LebMASH makes providers aware of the queer community’s differing, though specific, needs; helps physicians who want to work with LGBTQIA+ individuals more properly assist the community; and trains healthcare providers interested in training others on providing inclusive healthcare. LebMASH importantly created and maintains “LebGUIDE,” a directory of physicians who self-identify as being LGBTQIA+-friendly. LebMASH thoroughly vets the physicians through questionnaires and interviews them prior to listing them on LebGUIDE. However, as Zavi made clear to us, friendly does not mean knowledgeable, which is part of the reason why LebMASH focuses so heavily on ensuring that healthcare providers who want to offer inclusive care do so properly.

Zavi underlined several issues that LebMASH is working to tackle regarding the challenges faced by LGBTQIA+-inclusive healthcare. One of the most prominent problems is that there are still various popular misconceptions about the LGBTQIA+ community and their needs. For example, Zavi noted that some health and mental health providers still believe that being gay is a mental health issue and/or a disorder, support conversion therapy, and medicalize such identities. Various healthcare providers are simply unaware that being gay or trans is no longer considered a mental health disorder. They tend to scrutinize gay and queer relationships while knowing little to nothing about them and use highly outdated approaches to diagnosing LGBTQIA+ individuals, such as offering a therapy prescription for sexual and reproductive health issues. As Zavi put it to us, “We have medicalized the well-being of the entire community and yet we have not prepared the medical system to treat them well.”

Another issue LebMASH focuses on is the doctor/patient dynamic. Doctors often paradoxically rely on LGBTQIA+ patients to give them information due to a lack of knowledge on LGBTQIA+-focused healthcare, creating an uncomfortable and unhelpful environment where they aim to “fix” the patient. For example, many healthcare professionals, due to their ignorance and highly heteronormative approach to providing care, ask unhelpful and often discriminatory questions. Zavi pointed out that many ask gay men about their preferred sexual position and role (even though it is medically impertinent), ask who the “man” and “woman” is in a relationship, assume gay men are promiscuous and having unprotected sex, and bring up mental health unnecessarily when patients come for physical health needs (critically assuming a queer identity is a mental health issue).

Healthcare providers’ ignorance or lack of inclusion can also often worsen community health. For example, LebMASH has received several reports from civil society organizations and community members about an uptick in health issues related to inadequate access to information on PreP and PEP, HIV-prevention medications. Nongovernmental organizations and the Ministry of Public Health, the main distributors of PrEP and PEP, have broadly distributed the medication without offering sufficient information about it and necessary monitoring. This has led to a correlated increase in gay men being diagnosed with syphilis and chlamydia and incorrectly taking both medications, erroneously assuming they protect against all STDs. Zavi mentioned that other like-minded organizations have also recorded many lesbian women in Lebanon who think they cannot get STDs if they do not have sex with men. Highlighting how a popular public health misconception held by healthcare providers and community members could impact a community, this resulted in higher instances of lesbian women contracting STDs.

Zavi stressed that a lack of inclusive, highly available healthcare has caused some trans individuals to self-diagnose medication without medical intervention. Especially during the economic crisis and associated shortage of medications, specific medications such as hormonal replacement therapies sometimes became unavailable or highly expensive, leading some trans individuals to self-dose with whatever medication they could find. Others looking to transition more quickly due to the high cost of gender-affirming care may increase medication dosing or take medications based on what they have seen and heard their peers do without monitoring by a doctor, leading them to potentially take the wrong doses of medicines in the wrong forms.

Because of this, LebMASH also works hard to normalize medical concepts related to the LGBTQIA+ community to decrease misinformation and discrimination—and resulting health complications—against patients. It is important for medical providers to realize giving LGBTQIA+ individuals healthcare is “not a matter of choice,” Zavi urged. “You took an oath, respect that oath by doing no harm.”

When asked about addressing the various stigmas queer individuals face in Lebanese society, Zavi noted that LebMASH emphasizes the importance of using fact-based knowledge instead of cultural and religious beliefs to teach about proper inclusive care. LebMASH ensures healthcare providers in training know updated guidelines, are less defensive about personal views, and are comfortable asking the right questions. “With education,” Zavi urged, “behavior can be changed,” and healthcare providers can learn to do better.

Lastly, Zavi stressed that the current general lack of accountability and nondiscrimination laws in Lebanon allow healthcare discrimination to persist. For Zavi, there are several important ways to address this in addition to building the capacity of healthcare professionals. Passing nondiscrimination laws, insisting that institutions and organizations have zero-tolerance anti-discrimination policies, speaking up against injustice and inequity, and increasing accountability help fight such systemic healthcare discrimination.

Capacity building and legal and policy advocacy to combat institutionalized Discrimination (Tarek E. Zeidan, Helem)

We finally spoke with Tarek E. Zeidan, the executive director of Helem. As the first LGBTQIA+-focused NGO in the Arabic-speaking world, Helem focuses on supporting, leading, and creating the right environment for the queer liberation movement to succeed in the Middle East and North Africa—and Lebanon specifically. Helem was founded in 2001 and is community-based and community-focused. It provides several advocacy and legislation services to Lebanon’s queer community, offering legal and policy reform work, documentation of human rights violations, crisis response, digital rights advocacy, allyship and movement building, a community center for gathering, family support, and programming for parents. Helem also compiles research on Lebanon’s LGBTQIA+ community. Its thematic research focus is decriminalizing same-sex relations and gender non-conforming and non-normative identities, online hate speech, access to healthcare, education, housing, and housing equality. Aiming to build power alongside other human rights organizations in Lebanon, Helem’s community-centered approach leverages a “particular mobilization of community as a fundamental answer to institutionalized homophobia and transphobia in the region.” Consequently, Tarek emphasized that Helem works to be not the one-stop-shop for the LGBTQIA+ community in Lebanon but rather a place that “builds the capacity of humanitarian organizations to live up to their own mandate and help queer individuals get the services they deserve.”

Like Zavi and Nadia, Tarek told us about the various stereotypes pertaining to Lebanon’s queer community, many of which complicate LGBTQIA+ individuals’ ability to access the healthcare they need. Currently, Tarek said, one of the main myths LGBTQIA+ people face in Lebanon is that queerness and same-sex attraction are contagious diseases. Representing a certain sense of deviancy, LGBTQIA+ individuals are perceived to pose a threat to the family that is “coming for our children.” Tarek warned that the “amorphousness of accusations is important. The more vague they are, the more potent they are.”

Helem fundamentally works to combat and overturn the various practices stigmatizing or criminalizing queer people’s lives in the country. In addition to fighting for decriminalization, the organization also aims to help LGBTQIA+ people in unions, help them obtain housing, and end unfair labor practices. Helem refers queer individuals to necessary services around the country and provides information on healthcare and rights (and even has an activism boot camp to do so). Helem critically provides social media blasts and outreach for Lebanese LGBTQIA+ individuals on guidance on using drugs safely, avoiding blackmail and extortion, and dealing with potential legal issues they may face.

Tarek strongly emphasized how Helem works to join issue-based coalitions to set the queer community up for success in challenging institutions upholding systems of homophobia and transphobia. Many humanitarian organizations in Lebanon face a mountain of bureaucracy to get funding for providing any humanitarian services; if organizations can get substantial funding, Tarek said it often does not go to LGBTQIA+ people. Consequently, it is important for Helem to work horizontally alongside other like-minded organizations to build a more powerful like-minded coalition. Moreover, to improve the status quo, Helem takes a multifaceted approach to improve the lives of queer people in Lebanon, working alongside Oxfam, other Lebanese civil society organizations, and the United Nations to get LGBTQIA+ individuals better education, healthcare, and social institutions. For example, Helem is working on developing a resource project alongside SIDC for Lebanon, topographically mapping out LGBTQIA+-inclusive services based on community interviews and knowledge of local resources.

With its community-first approach in mind, Helem’s legal advocacy work has also been highly successful. In 2022, Helem helped stop Lebanon’s Ministry of the Interior’s June 2022 ban on any gathering that promoted what the minister of the interior called "the phenomenon of sexual deviance.” By filing a lawsuit alongside The Legal Agenda, Helem’s challenge led Lebanon’s high court to suspend the decision in November 2022. Noting a glass ceiling with how far organizing tactics that are successful in the West can go in Lebanon, Tarek told us Helem constantly works to reassess, restrategize, and optimize its organizing tactics. Helem’s approach can be characterized by a very vocal and confrontational approach to advocacy, which has led religious establishments; local non-state actors, such as the “Soliders of God”; and local law enforcement to aggressively oppose its work. However, such marginalization and discrimination have only galvanized Helem’s movement toward achieving queer liberation and its fight to counter politicians who support prejudiced ideologies. As Helem has become increasingly successful, such political and community leaders, as Tarek put it, "unfortunately discovered the massive political windfall of developing moral panic around gender and sexuality.”

The battle to end institutionalized homophobia and help LGBTQIA+ individuals achieve equitable access to inclusive healthcare is still ongoing in Lebanon. Where does the state's responsibility lie in offering sustainable resources for all without discrimination?

The battle to end institutionalized homophobia and help LGBTQIA+ individuals achieve equality and equitable access to inclusive healthcare is still ongoing every day in Lebanon. As the right to access sexual and reproductive health rights remains dismissed in a country struggling with deep socioeconomic crises, LGBTQIA+ individuals and other marginalized people pay the highest price while they resort to relying on alternative resources and civil society institutions. Thankfully, these organizations are working hard to provide short- and long-term solutions today to help marginalized communities. Where does the responsibility of the state, however, lie in maintaining sustainable resources for all individuals without discrimination?

Raseef22 reached out to several human rights organizations concerned with LGBTQIA+ individuals in Lebanon during the writing of this report. Three organizations—Helem, LebMash, and SIDC—agreed to conduct interviews with Raseef22 staff members. In addition to these organizations, The A Project, the Arab Foundation for Freedoms & Equality, Hivos, Marsa, MOSAIC, Proud Lebanon, and Salama provide advocacy, sexual and reproductive health services, and other critical resources to the LGBTQIA+ community in Lebanon. LebMash also provides a list of LGBTQIA+-welcoming resources in Lebanon.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!