‘ANZAC Day’ is a national day of remembrance that has become a cornerstone marking both the popular and political memory of Australians and New Zealanders alike. It is widely celebrated, with its stories now taking up an important portion of both the school curriculum and folk tales within the two countries — so much so that they have turned into a sort of mythology that some who wrote about it like to call it “Anzacian”.

With time, ‘Anzac’ became known as a day “of honoring and commemoration for those who served and died in all wars and conflicts”. However, it was — in name and in practice — primarily founded to honor members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) who fought in Gallipoli against the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

The Battle of Gallipoli, which began on the 25th of April 1915 and lasted for nine months, left half a million dead and wounded. At its core were the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps that fought side by side for the first time. This joint effort remained firmly ingrained within the national memory as the milestone marking the two countries’ coming of age that led them to step out from under the shadow of the British Empire.

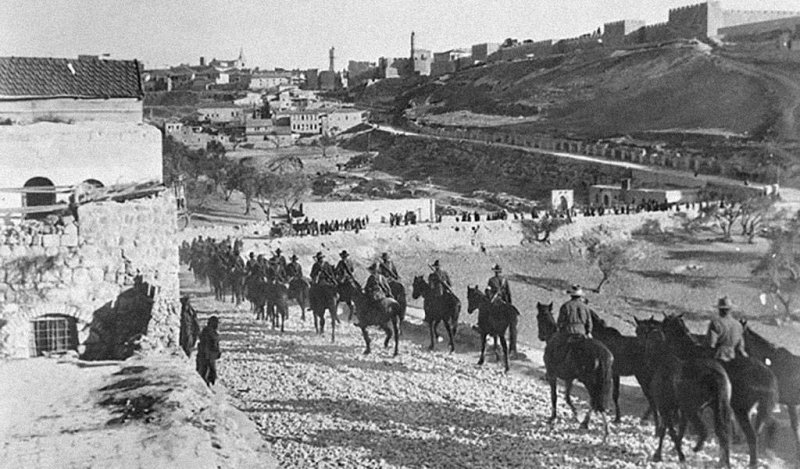

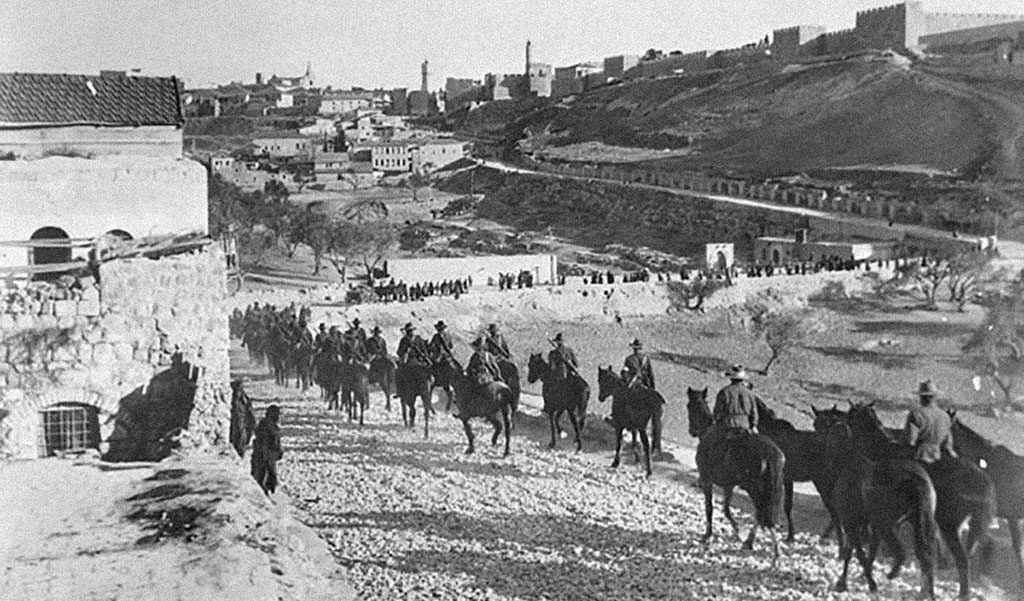

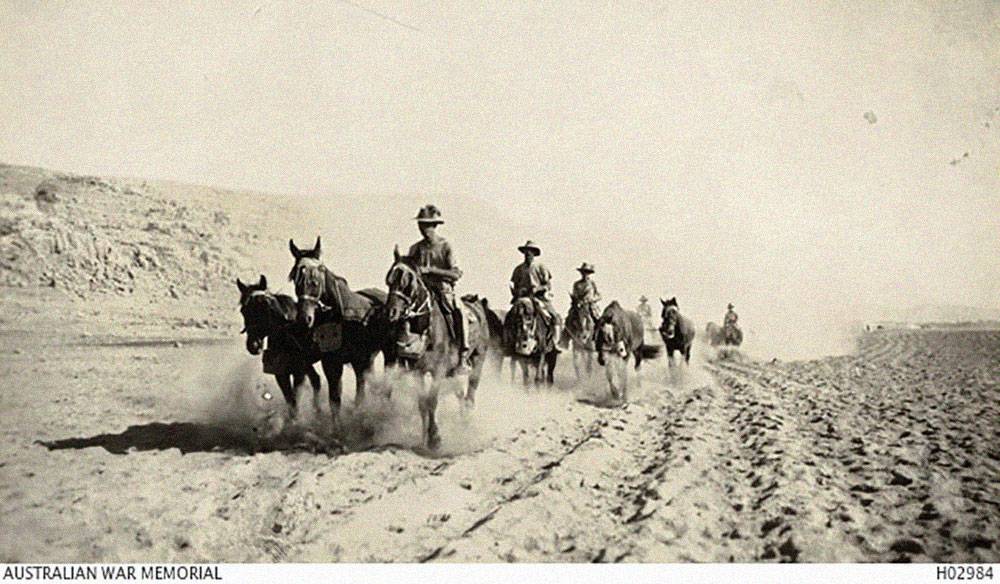

Two years later, the name ‘Anzac’ made an appearance once again. It was during the Battle of Beersheba (in southern Palestine), which took place during World War I — specifically in October of 1917. At that time, Australian and New Zealand cavalrymen (the Anzac Mounted Divisions) seized the area from Ottoman forces.

“Anzac Soldiers… A Part of the History and Memory of Israel”

Every October, the descendants of these men return to Beersheba dressed as cavalrymen to roam the region on their horses, recalling their ancestral “heroism”. Israeli, Australian, and New Zealand officials gather in the area to revive the exploits of the horsemen who defeated the Ottomans in a battle that paved the way to Jerusalem.

It is true that the inception of Israel is directly tied to the “Balfour Declaration”, but Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has repeatedly reiterated that this battle paved the way for the creation of the “State of Israel”. He said, “Anzac soldiers are part of the history and memory of Israel... and had not the Australians and New Zealanders overthrown Ottoman rule in Palestine and Syria, the Balfour Declaration would have remained mere ink on paper.”

Much has been written about Gallipoli and Beersheba and their role in reshaping the Middle East, but the roles of Australia and New Zealand have fallen short of gaining the attention of those who paid the price for that new formation. Among the markers almost absent within that role — and paradoxically almost completely absent from the Australian-New Zealand narrative — is what the Australians and New Zealanders committed on the 10th of December, 1918 in the small village of Sarafand (known as Sarafand al-Kharab) — not to be confused for the greater Sarafand village (Sarafand al-Amar).

The “Sarafand Massacre” and its Forgotten Details

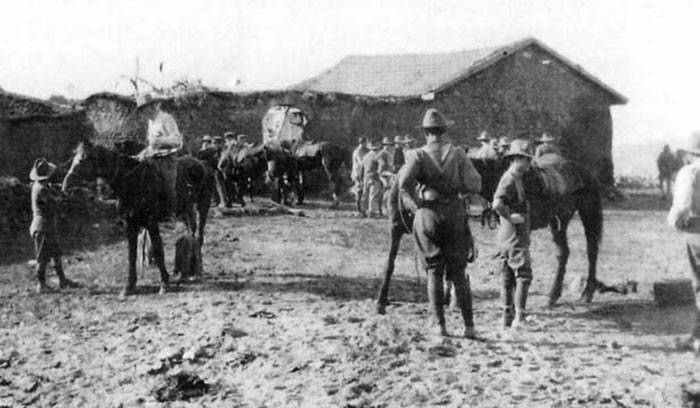

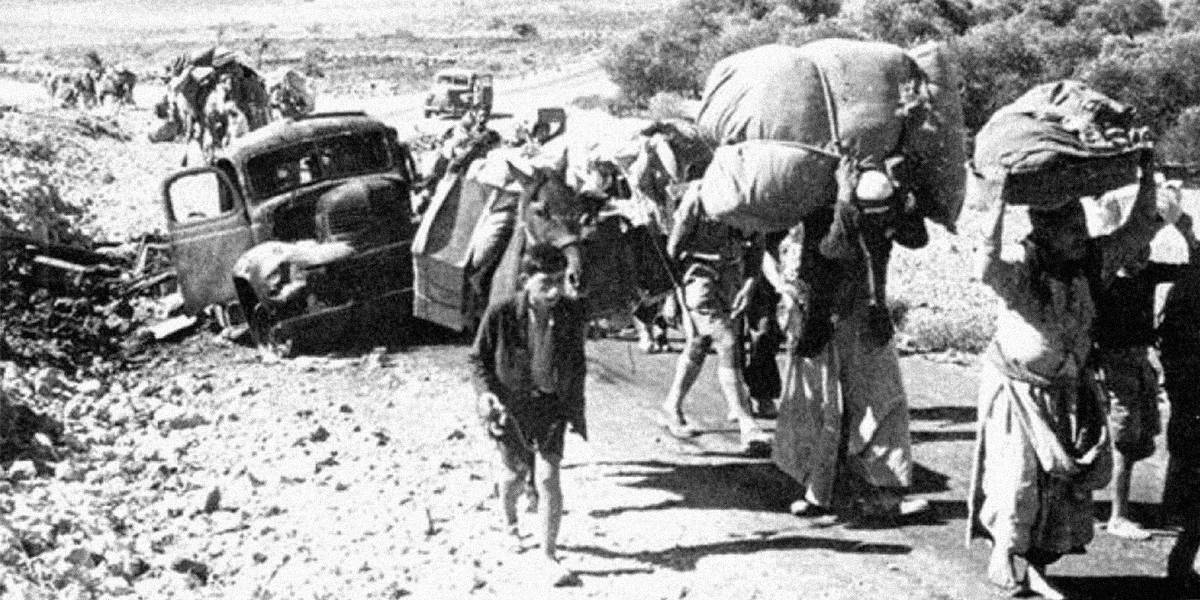

Early on the night of December 10th, 1918 — that is, following the end of World War I — about 200 Anzac soldiers surrounded the village of Sarafand (also dubbed the Surafend Affair). After expelling the women and children from the locale, the soldiers descended on the residents carrying heavy sticks and spears with the aim of killing every young man over the age of 16. It is estimated that they massacred somewhere between 40 and 120 before they set the huts on fire and killed the animals there. The fires lit the countryside region for miles around. Then they moved on to the nearby Bedouin camp, which they also burned to the ground.

It is true that the inception of the state of Israel is directly tied to the “Balfour Declaration”, but Israeli PM Netanyahu said, “If it weren't for the Anzac soldiers, the Balfour Declaration would have remained mere ink on paper.”

On December 9, an abusive New Zealand soldier, Leslie Lowry was stabbed and as he died, he told his comrades he was killed by an Arab thief... That is when the “revenge party” began.

There are two separate accounts detailing the causes of this massacre, one Western and the other Arab, but what is agreed upon by both is that it took place following the killing of a 21-year-old New Zealand soldier named Leslie Lowry on the night of December the 9th.

Paul Daley, the Australian writer, journalist, and storyteller, took interest in all the varying stages of his country’s corps’ participation in World War I. His interest took the forefront ever since he began writing about the ‘Battle of Beersheba’, documenting it in the book “Beersheba: Travels Through a Forgotten Australian Victory”, which he published in October of last year. However, the writer has now returned to talk about new discoveries that changed his view about many of his ideas about the aforementioned “victory”, specifically what he found in the Australian archives about the “Sarafand massacre” (also known as the Surafend Affair).

According to the Arabic narrative, soldier Leslie Lowry always troubling Sarafand residents with his constant pursuit of women. The reason for his killing was a problem over this — and not theft as he had claimed as he lay dying

The details of this massacre remained scarce, and while the role of New Zealanders was mentioned in the record, the Australian role continued to be absent until Daley resurrected it from the archives. He called on the Australians to take responsibility for it, saying, “The Surafend massacre shows that the core business of good history must always be the preservation of memory.”

In the archive, Daley found a recording of an Australian soldier in the Anzac Mounted Division (the cavalry horsemen) saying that he and his comrades drank enough rum (an alcoholic drink), narrowed their siege on Sarafand, and then attacked the village with spears and bayonets. The soldier known as Ted O’Brien admitted, “The Bedouins were evil... but the massacre was really bad, it was unjust.”

In the recordings, O’Brien talks about the horsemen, their presence in Palestine, and his visits to the pyramids of Egypt. There was nothing in it that caught the eye of Daley until he came across a recording with the “Australian horseman” recounting how the “New Zealanders and Australians went to the Bedouin village and killed its men with bayonets and broke up [destroyed] the buildings.”

O’Brien’s squadron was there, and he didn't know why he had gone there or why he had fought, but the rum was running its course, according to him.

Regarding the massacre, according to Daley, there were many secret investigations (by the Brits, due to the participation of some Scots at the time, and also by other Australians and New Zealanders), but they remained in the forgotten part of history in which writers devoted themselves exclusively to the horsemen’s heroics.

The “Revenge Party”: Between the Two Narratives of Theft and Debauchery

Daley spent months combing through the Australian and British archives — given the $600 million dollar compensation that Australia had devoted to the memory of its horsemen — to find that these people did not distinguish between the nomadic Bedouins and the town Arabs of Palestine. In their journals and writings, the Anzacs also linked the “miserable and starved” residents of the region to the “Australian blacks”, as they put it. The blatant racism of this comparison facilitated the Australians’ “racially-charged attitude” and reactions towards them, especially since the Australians and New Zealanders saw the Arabs as thieves and spies.

According to Australian archives, following the armistice of 1918, the Anzac brigades were gathered in the Jewish settlement of ‘Rishon LeTsiyon’ near the Mediterranean. The Australians were liked by the Jews there, and while they waited to repatriate, there was plenty of food and alcohol on hand. They spent their time horse racing in addition to playing football and cricket.

The story tells of how the horsemen suffered from thefts committed at the hands of the residents of Sarafand and the Bedouins next to the village. On the night of December 9, soldier Lowry was chasing a thief who then shot him dead when he was cornered. Before he died, he told his comrades about the thief and informed them that he had gone to the Bedouin Arab village. That is when the “revenge party” began.

The Arabic account differs regarding what went down that night. There was a bar in ‘Rishon LeTsiyon’, which was considered one of the most important Jewish spy cells before the Nakba, and there the soldiers residing in the settlement awaiting return to their homeland were receiving alcohol in large quantities. They were also being pushed by the Jews — after being taught Arab phrases that violate honor — to wander and practice debauchery between Sarafand homes. This was all done in the hope that they would force the residents of the village to sell their homes and move away from the army camps.

According to the Arabic narrative, soldier Leslie Lowry was one of them, always troubling Sarafand residents with his constant pursuit of women, and the reason for his killing was a problem regarding this particular matter — and not theft as he had claimed as he lay dying.

Compensation for the Perpetrators?

In the end, the investigations led by the aforementioned three parties (the Brits, the Australians, and the New Zealanders) did not conclude who was directly responsible for the massacre. The British accused the New Zealanders and the Australians. The New Zealanders blamed the Australians, and, naturally, the Australians blamed the New Zealanders. Moreover, the British demanded compensation for the costs of transporting the residents of the village (which was under their jurisdiction) to another area, also demanding further compensation for the victims.

A few days following the massacre, British General Edmund Allenby declared that the Anzacs were “a bunch of murderers” and “wiped his hands of them for good”. The massacre would then return to make a very timid appearance within a few pages in Australian history, eventually leading towards its near total absence within its records.

Daley’s return to the archives was in the context of a call to protect the Anzacs’ ‘heroisms’ by confronting the dark afn black points in their history, while our return to it appears to be just another new reminder of the numerous massacres committed in the region, with the only compensation for the spilt blood (whether material or moral) only being collected by the perpetrators themselves or their very own allies.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!