During the 1990s – and specifically the year 1992 – the first public appearance of the al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (“the Islamic Group”; also transliterated Al-jamāʻah al-islāmīyah) took place in the Imbabah neighborhood. The area was suffering from panic and devastation following the earthquake that struck Egypt and devastated that neighborhood. I recall how the people of the region crowded together along the railway line – the same one that Mohammad Ali established to link the wheat arsenal with the rest of the provinces – and they set up camps there. Everyone was afraid of after-shocks, afraid of their damaged homes crumbling above their heads, afraid of the ruthlessness and true brutality of nature. The families gathered and worked together to cope with the crisis. This is when the group appeared to provide the necessary assistance, participate in the restoration of homes, and call on people to reconsider religion as well as draw closer to God. The people of the neighborhood welcomed them with genuine warmth and were thrilled by the group’s care for them.

The earthquake finally ceased its activity to become a near memory that leaves minds trembling in its wake. But the group’s activity did not cease. It went on to expand into reconciliatory sessions between large families, involvement in the marriages of poor women, and food packages distributed to those in need. These actions limited the role of the government and at the same time expanded the range of al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, which gained enough confidence from the region’s residents to push their sons into joining it. I was one of those sons. When I did so, I became the youngest member of the group.

Music and pop songs disappeared from stores and taxis, replaced by the tapes of Sheikh Kishk and Sheikh Abdel-Rahman, the founder and godfather of al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, we were all pulled in.

At dawn, I head to the small al-Radwan Mosque for morning prayers. I pray with the brothers and enjoy special care from their emir Sheikh Khalid. I attend course sessions, and I go around with them to address people on the streets and urge them to hold on to their religion, while wearing short robes and with my head wrapped in a keffiyeh and a turban.

Not only did this transformation happen to me, but the region gradually gained a new character, as if it belonged to another culture from a distant, far and different era. I no longer saw a single woman without her niqab. As for the girls, they were introduced to the veil, while the young men wore their common Pakistani attire. Even popular music and songs disappeared from the stores and taxis, to be replaced by the tapes of Sheikh Kishk and Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the true founder and godfather of the group. Even festivities and celebrations – that Imbabah was well-known for – changed as well. Unlike the previous norm, they now host no dancers or singers, but are rather Islamic celebrations in which the groom rides a white horse and roams the streets and alleys, while the bride stays with other women – all to the beat of new anthems and tambourine drums.

One or more members of the group could be found in every household. No one could even think of or consider sin. Everyone was promoting virtue and forbidding vice, even inside their own homes. I remember, for instance, how my friend’s older brother once broke the TV set at his house because his father was watching an Ismail Yassin film.

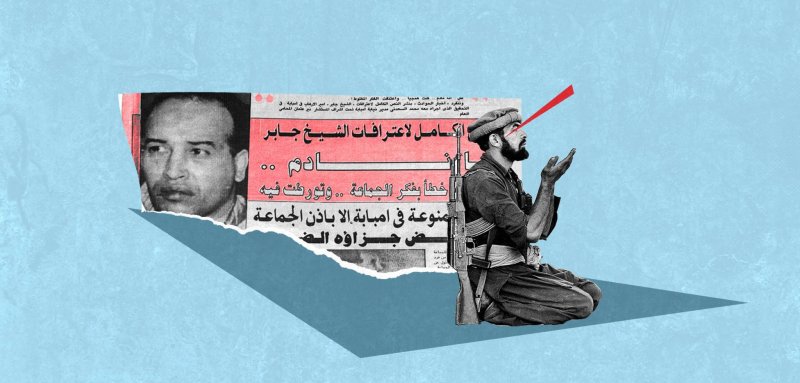

Meanwhile, Friday was always different from other days. We would wake up just before dawn and go to the largest mosque in the community, Al Rahma Mosque in Al Basrawi to which all the brothers flock from every direction. We pray the morning prayer and head to the camp – which is a vast empty lot of land – and we divide into teams. Each mosque and region has its own emir and assistant emir. We play football and ping pong, participate in religious competitions, and celebrate the winner. Before Friday prayer at noon, we go back to the mosque and listen to the sermon from our elder, Sheikh Jaber Rayan. He is the emir of the al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya in Imbabah, and we gave him the title, ‘commander of the faithful’. The sermons were mostly against Zionism, cursing Jews and Christians along with every person on the face of the earth that does not know Islam, with a special focus on the persecution that every Muslim goes through in the world’s countries. After the Friday prayers, we gather over food in circles around trays and eat with three fingers while sitting cross-legged. We return to our homes after sunset following an immense charge of faith and a strong desire for Jihad.

Everyone was promoting virtue and forbidding vice, even inside their own homes. I remember, for instance, how my friend’s older brother once broke the TV set at his house because his father was watching an Ismail Yassin film

One night I wished I had Mazinger (giant super robots from a cartoon series). I imagined myself driving it like Maher, using it to face the enemies of Islam, killing armies of heathens, and liberating Jerusalem from the grip of the Zionists. That wish dominated me for a long time, until the night of Rabat (or binding) came upon us. It was a very special night that only trusted members could attend. This night was held every little while in a different mosque. That night, it was the turn of the Radwan Mosque – my mosque. Long after the evening prayer, the door of the mosque was locked from the inside. A brother went up to the podium and set up a TV and video player, and the show began: various trainings for brothers in far-away lands, mountains, deserts, along with brothers crawling underneath barbed wires with weapons. A man appears and identifies himself as Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian, calling on all brothers to join the mujahideen everywhere. Other scenes from Bosnia and Herzegovina appear; corpses ravaged by flies, killing and slaughtering, and piles of rotting bodies. Other scenes of the Palestinian uprising also make an appearance; tanks bulldozing houses and uprooting olive trees, a woman embracing her baby and crying, a child of about my age throwing a rock at an armored vehicle as he recites, “I did not throw even when I threw, but God threw it”. He throws the rock and the armored vehicle explodes.

I was quite taken by the entire thing; enthusiasm, humiliation, pride, and a frenzied desire to participate – all conflicting and contradictory feelings. However, my eyes were distracted with the grand elder sheikh sitting in a corner under dim lighting. I noticed that everyone was avoiding approaching him. No one would approach him except Sheikh Jaber, exchanging a word or two with him and then nodding his head with excessive understanding and respect. I understood that the grand elder sheikh is Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman. He was visiting us, and the brothers had talked about him a lot before, weaving myths about his mighty personality and his ability to manipulate security despite being blind. They possessed a special art in crafting stories about their elder – perhaps one could even call it the art of myth-making – and here was the mighty legend himself, asking to see me. “Me! Why?” I ask Sheikh Jaber, and he tells me, “Do not be afraid. I told him about you. Just reply with one word.”

“Would you like to be a Mujahid with us, Sheikh Amrouch?” Of course I would love to, and I assured him that I would be a great warrior just like Khalid ibn al-Walid.

I wrote about this incident in my latest novel, “Law of Survival” and I will continue to write about it and retell it. At the time I approached the old sheikh. A white film covers the eyes. He is blind. Sheikh Jaber pushed me gently, so I stepped forward in spite of myself, until I was right in front of the sheikh who asked me about my name, and then about my brothers. When he heard that I had a younger brother, he seemed comforted and relieved. Then he went back to his questioning, “Would you like to be a mujahid with us, Sheikh Amrouch?” Of course I would love to, and I assured him that I would be a great warrior just like Khalid ibn al-Walid. He smiled and then asked, “What does your father work in?” I told him that my father draws and paints most of his time, and he also loves sculpting statues. I can never forget his reaction. His face transformed and scrunched up as if an insect had gone into his mouth. He did not respond, just signaled with his hand for me to leave, and I left. I did not know at the time that art had saved me from an ugly and unknown fate. I did not know that art would always be the most powerful weapon against outdated and backwards thinking – because it is, for it was the enemy of that group. Of course, artists were included as their enemies too. So thank the heavens that gave me a father who was one of these artists.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!