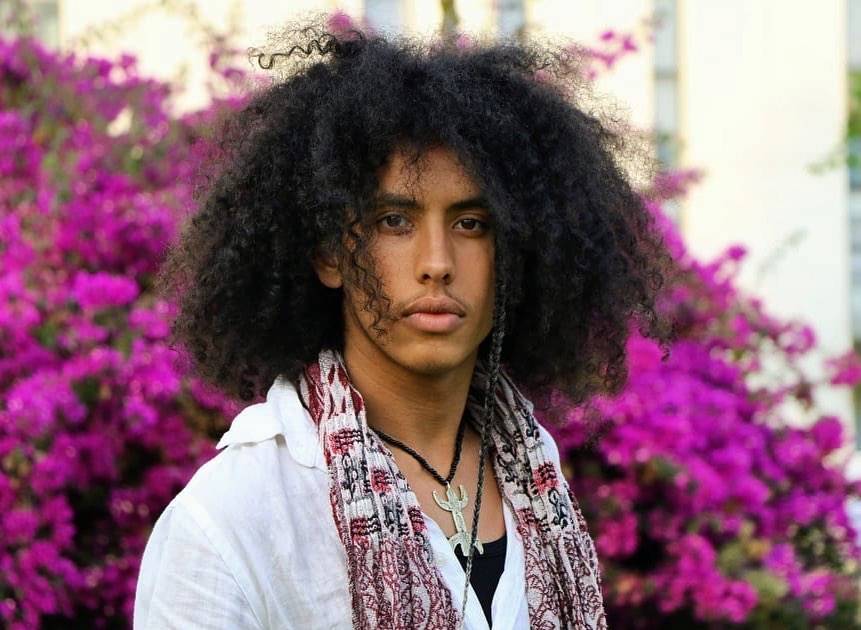

On Tuesday October 6th, a lower court in Sidi Kacem, Morocco sentenced gender-non-conforming Moroccan artist Abdelatif Nhaila to a suspended prison term of four months and a 1,000 dirham fine. Abdelatif was found guilty of “outrage to a public agent in the exercise of his duty” and “violating the sanitary state of emergency.” His supposed “crime”? Abdelatif went to his local police station to file a complaint for defamation and death threats after he got targeted by the violent online outing and hate speech campaign sparked by a Moroccan Instagram celebrity. Instead of attending to his case, police officers insulted, humiliated and arrested him.

Last April, Turkey-based transgender influencer Sofia Taloni instructed her tens of thousands of followers on how to expose closeted queer men by creating fake profiles on gay dating apps. Her stunt sparked a devastating online outing campaign across Morocco, where homosexuality remains criminalized and punishable with up to three years’ imprisonment. In the middle of a strict quarantine, with no escape from potentially abusive domestic situations, hundreds of gay men saw their private pictures exposed online.

A few days prior, Abdelatif Nhaila had accepted the influencer’s invitation for an Instagram Live conversation on an unrelated topic. During their discussion, Sofia Taloni began speculating about Abdelatif’s sexual orientation, made abusive comments about his style and attitude which she deemed not to be masculine enough, and went as far as to call on her followers in the young artist’s hometown to rape him. Following the influencer’s incitement, a Facebook page targeted Abdelatif Nhaila, posting his pictures, making assertions about his private life, and defaming his character.

Like the countless other men caught up in the outing campaign, Abdelatif received an onslaught of insults as well as death and rape threats. Fearing for his safety but knowing his rights, he headed to his local police station to file a complaint against Taloni and the admin of the Facebook page. However, what should have been a routine legal procedure quickly turned into a nightmare.

A transgender influencer in Morocco outs Abdelatif and calls on men to rape the effeminate artist, Abdelatif seeks police protection, instead they abuse him and Abdelatif ends up with a 4 month jail term

Abdelatif, a daring young artist who has consistently used his theatre productions and performances to champion progressive causes and defend the rights of minorities in Morocco, said he faced verbal abuse and discrimination at the hands of the police. In an interview with writer and journalist Achraf Remok, the actor explained: “When I first arrived at the station, the police officer who was supposed to take my claim looked at me in such an odd way. He stared at my piercings, my afro-hair, and my clothes. I immediately felt that he conducted prejudices about me. He then said, ‘we are not working today, go away.’” Abdelatif continued asking the officer to hear his case, pleading: “My life is being threatened. Just think of me like your son.” With palpable disgust, the agent spat back: “if you had been my son, I would have burned you.”

As Abdelatif insisted upon his right to file the complaint, the police officer quickly turned on him. He claimed his circulation permit was not appropriately filled (Note: Moroccan citizens were required to carry a permit issued by local authorities in order to go outside for essential trips during the COVID-19 lockdown). Before he knew it, Abdelatif was arrested and held in custody for two days, during which he was repeatedly denied his rights to a phone call or to legal representation. In the face of this onslaught of abuse and injustice, Abdelatif had two severe anxiety attacks while in custody which required him to be transferred to an urgent care unit.

Abdelatif was charged with “outrage to a public officer” and “violating the sanitary state of emergency,” and sentenced to a four-month suspended prison term and 1000 dirhams fine. To add insult to injury, Abdelatif was also ordered to pay a one-dirham symbolic restitution to the very officer who abused him. Since then, the young artist has filed an appeal to overturn the court’s decision, which he described as a “huge injustice.”

Moroccan LGBT activists, human rights defenders, and progressive artists have all expressed their solidarity with Abdelatif Nhaila throughout his trial. In an op-ed on OpenChabab, LGBT rights activist and columnist Soufiane Hennani wrote: “Today, to support this militant artist is to support freedom of gender expression, freedom of expression generally, and the right to bodily autonomy. We refuse that in the Morocco of 2020, donning a khelkhal (traditional bracelet), having wild hair, and wearing a piercing could be a crime. We will repeat as many times as it takes: a Queer generation, passionate about art and culture and about freedom is on the way. Not to see it coming is a denial. To repress it is a crime against youth.”

When Looking Different Becomes A Crime: Queer and Trans People Face Police Abuse in Morocco at Alarming Rates

Sadly, Abdelatif Nhaila’s case is not the first time that Moroccan police joined in on the bullying against queer people or people presumed to be homosexual based on their gender expression.

In 2019, for instance, a trans woman named Manal got involved in a minor car crash on her way back from a new year’s eve party in Marrakech. When the police showed up, they dragged Manal out of her car and humiliated her in front of a crowd that had gathered around the scene. Instead of protecting Manal from the mob hurling homophobic obscenities and threats at her, the police agents took photos of her, mocking her dress and make-up. The officers then leaked those photos to social media and the press, along with pictures of Manal’s ID, thus exposing her identity and putting her in immense danger. Although the officers responsible for leaking those pictures were admittedly reprimanded, the damage was already done. Manal was forced to seek asylum in France because she was no longer safe in Morocco.

Local activists see these cases as mere symptoms of a much wider systemic problem. A recent study by the organization Association Akaliyat among nearly 250 LGBTQ people — the largest of its kind ever conducted in Morocco —revealed that the community was disproportionately policed and criminalized. 29% of participants said they had been arrested or detained at least once, in most cases over suspicions of homosexuality. Other reasons mentioned by participants included being detained because of their gender expression, after defending themselves from aggressions, or in missing person searches launched by the families they had fled from. Transgender and non-binary people were twice as likely to have been arrested than cisgender queer people, indicating that gender non-conformity remains heavily repressed by Moroccan authorities.

Moroccan actor, director, and performance artist Abdelatif Nhaila said he faced police abuse and discrimination merely because of his hair, his clothes, and his non-normative gender presentation.

More alarming still is the treatment queer people receive when they’re held in custody. Echoing the nightmare scenario faced by Abdelatif Nhaila, over 63% of LGBTQI people who had experienced an arrest said they were mistreated by local authorities, and only 15.3% were able to access a lawyer. Cisgender lesbian women and trans women were the most vulnerable to police ill-treatment, with respective rates of 75% and 77.5%, highlighting the ways in which homophobia, misogyny, and transphobia intersect for queer and trans women.

As their identities continue to be criminalized under the Moroccan penal code, queer and trans people are very seldom able to seek justice. According to the same Akaliyat study, only 14% of LGBTQ victims of violence had filed a complaint, largely citing fears of retaliation, outing, and prosecution by authorities. In 2019, Dina El-Omary, a Moroccan trans activist, was attacked and kicked out of a café in Tangier. In an interview with Moroccan magazine Plurielle, she admitted: “I’m scared of going to the police and ending up being the one arrested because of my make-up, instead of those responsible being arrested.” For the queer and trans community, cases like Manal’s or Abdelatif Nhaila’s only serve to reinforce these fears, confirming their distrust of the entire Moroccan criminal justice system.

In the face of these systemic abuses, the Moroccan government chooses to look the other way. In September 2017, the Moroccan delegation to the United Nations Human Rights Council, led by Human Rights Minister Mustapha Ramid, rejected recommendations from several member states to decriminalize homosexuality. Paradoxically, the delegation not only accepted a recommendation to “take urgent measures to repeal the norms that criminalize and stigmatize lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex persons and investigate and punish the perpetrators of acts of discrimination and violence against them,” it claimed that the recommendation was already “fully implemented.” Completely disregarding the lived realities of its queer citizens, the government’s stance was that the Moroccan constitution already fully protected all citizens against discrimination and stigmatization and that no further measures were necessary to protect LGBTQ people.

A mere week after he was in Geneva arguing that Morocco already protects LGBTI people against discrimination and stigmatization, Mustapha Ramid came under fire for calling gay people “scum” in an interview. The Minister of Human Rights, formerly in charge of Justice and Liberties, has made multiple homophobic comments in recent years, illustrating that institutional homophobia in Morocco doesn’t end with the police, but extends all the way to the highest levels of government.

Between Abuse and Homelessness: Covid-19 Lockdowns Heightens Concerns Over Domestic Violence

Abdelatif Nhaila was accused of violating Morocco’s Covid-19 quarantine provisions because his circulation permit had not been filled out properly according to the police. Abdelatif argued in court that he carried the permit exactly as he had received it and that any omissions were the responsibility of the issuing authorities. Regardless of whether the actor had the appropriate documentation, however, it remains very troubling that a victim of abuse and death threats could be arrested and prosecuted merely for leaving their house to seek protection from authorities. The case raises many questions about the vulnerability and isolation of gender-based violence and domestic abuse survivors during the Covid-19 lockdown.

In April, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres raised alarm over the rising rates of violence against women. “We know lockdowns and quarantines are essential to suppressing COVID-19. But they can trap women with abusive partners. Over the past weeks as economic and social pressures and fear have grown, we have seen a horrifying global surge in domestic violence,” Guterres said, urging governments worldwide to center prevention and response mechanisms to gender-based violence in their pandemic response plans.

During the height of the first wave of the pandemic, Moroccan citizens were required to carry an official permit attesting they had a legitimate purpose to leave the houses. However, authorities issued only one such permit per household, authorizing a single member to leave the house for essential trips. Owing to patriarchal gender norms, this permit overwhelmingly went to the “man of the house,” exacerbating existing gender inequalities. For many women, this effectively meant being trapped with their abusers, with no access to safe shelter or support systems. Indeed, even before the pandemic, the rates for gender-based violence in Morocco were staggering. A 2019 study by the Moroccan Higher Planning Commission found that 46% of women in the country experienced domestic violence.

Likewise, several LGBTQ people in Morocco also experienced heightened domestic violence, particularly in the wake of the outing campaign. One 23 years old man who was outed and kicked out by his brother told Human Rights Watch: “I have been sleeping on the street for three days and I have nowhere to go. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, not even my close friends are able to host me.” In the absence of any LGBTQ+ shelters in the country, the community had relied on informal queer solidarity networks to offer emergency housing to vulnerable individuals and those kicked out by homotransphobic families. As intercity travel became prohibited, this last lifeline for queer people became inaccessible, forcing many to make the impossible choice between violent abuse and homelessness.

Instead of protecting Manal from the mob hurling homophobic obscenities at her, Morocco's police agents took photos of her, mocking her dress and make-up. The officers then leaked those photos via social media along with pictures of Manal’s ID

No Longer Safe on the Web: MENA LGBTQ People Face Outing and Hate Speech Online

While 2020 has been a trying year for communities around the world, LGBTQ people in the Middle East and North Africa truly could not catch a break. The wave of outings and harassment that saw Abdelatif Nhaila and hundreds of Moroccan gay men targeted this spring was but the first of several homophobic hate campaigns to arise in the region this year. Social media and online dating applications, once a somewhat safe haven allowing persecuted communities to meet and connect, are now being weaponized against queer individuals increasingly frequently.

For instance, a Human Rights Watch report released on October 1st revealed that Egyptian security forces have been using Grindr and other gay dating applications to hunt down and entrap LGBT people. The previous month, a Tunisian Instagram influencer named Lady Samara went on a homophobic rant in which she called gay people “mentally sick perverts” and claimed they were brainwashing children to become homosexual. Not unlike the Moroccan Sofia Taloni, she urged her followers to speak out against homosexuality, sparking a wave of hate speech, harassment, and cyberbullying against the Tunisian LGBTQ community.

During the summer, in the wake of the tragic death of Egyptian queer feminist activist Sarah Hegazy, who had been jailed and tortured three years prior for waving a rainbow flag at a concert in Cairo, the entire region saw yet another surge in online abuse against queer people. Posts included incitements to violence, death threats, and countless despicable publications that gleefully celebrated the young activist’s suicide. In Morocco, some users also created Facebook groups dedicated to identifying queer individuals and organizing gay-bashing attacks on LGBTQ communities.

Moroccan LGBTQ rights organization Association Akaliyat warns its followers about gay-bashing campaigns organized via Facebook groups. The screenshot attached reads: “Hi. About those f*ggots, there is a spot where they gather in Agadir, specifically in [redacted]. They’re always there until midnight. Let’s set a time to go give them a beating and come back. Whoever wants to meet today, comment here.”

A coalition of over twenty LGBTQ organizations from across North Africa urged Facebook to step in, accusing the company of dragging its feet when it comes to enforcing its hate speech community standards in the region. In an open letter, activists explained “although the MENA LGBTQI+ community has been reporting thousands of Arabic hate speech posts [...] most of these reports were declined because the content ‘did not contradict the Facebook community standards.’” The coalition called on Facebook to protect the safety of gender and sexual minorities, by providing LGBTQ-specific training to Arabic language content moderators and by applying its policies against anti-LGBT hate speech uniformly across the world, including in the Middle East and North Africa.

In response to these demands, the Facebook administration reportedly agreed to place greater priority on reviewing hate speech reports based on sexual orientation emanating from the MENA region. The company vowed to take down posts targeting specific queer individuals but maintained that attacks against LGBTQ “concepts/ideology” did not violate its standards because they were a matter of freedom of opinion and expression. Such permissible posts could therefore include describing homosexuality and transness as diseases or perversions, promoting forced conversion therapies and other abusive practices against queer people, spreading misinformation linking homosexuality to pedophilia, or peddling conspiracy theories about nefarious “LGBT lobbies,” to only name a few of the recurring themes in homophobic posts seen across the region.

While acknowledging Facebook’s engagement as a small step forward, these measures were far from good enough according to activists. They contended that “homosexuality is not an ideology but an essential component of the identity of individuals,” arguing that discourse that incited hatred against queer identities could directly lead to increased physical violence and persecution against LGBTQ individuals in the region.

Further, LGBTQ organizations expressed concern about the impact of such violent content on the mental and emotional health of Middle Eastern and North African queer people, most of whom are already criminalized, marginalized, and excluded from accessing many psychosocial services. A region-wide report titled Hate Speech Spreads Like Wildfire, warned that over 77% of queer people surveyed had experienced online hate speech or harassment based on their sexual orientation or gender identity in the weeks leading up to the survey. Of those, about half said they had felt severely depressed and hopeless as a direct result of seeing such posts, and nearly 1 in 4 said they had had ‘very strong’ thoughts of self-harm, with some participants even mentioning having been driven to attempt suicide. One young gay man quoted in the report pleaded: “I wish from the bottom of my heart that this issue will be taken seriously by Facebook, so we are no longer exposed to all this hatred and emotional harm.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!