In April of 2003, a delegation of attorneys from Darfur entered Sudan’s presidential palace on an urgent humanitarian mission. Horrified by the surging massacre of Black Muslim civilians in Darfur, the civic leaders had documented dozens of violent attacks on villages by government militia. They desperately called on Sudan’s then-President Omar Al Bashir to stop the murderous raids. Hundreds of thousands of Black lives hung in the balance.

Rather than meet the human rights lawyers personally, Al Bashir delegated his top lieutenant, Qutbi Al Mahdi, to handle the matter. The former head of Sudan’s Intelligence Service, General Al Mahdi served as Presidential Adviser on Political Affairs. He listened to the impassioned pleas of the Darfuri emissaries to prevent an unfolding genocide – and then did nothing. As a Human Rights Watch account of the meeting dryly notes, “There was no follow up on their recommendations to the president.” 300,000 Black Muslims would soon be killed and 2.5 million more made refugees in a modern-day genocide.

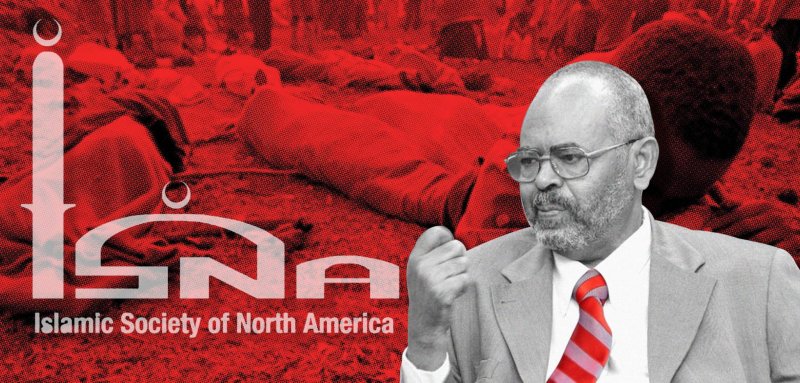

What the Darfuri lawyers likely did not realize was that Al Mahdi not only served as an enabler of their people’s slaughter but also as former leader of America’s preeminent Muslim organization: the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA). Al Mahdi’s transition from ISNA President to Sudanese Presidential Advisor reveals how Islamists used Muslim American institutions for their own overseas political agenda and further entrenched systemic racism. In so doing, innocent civilians, like the women and children of Darfur, became their forgotten collateral damage.

As ISNA gathers for its latest annual convention on September 5, it remains unclear if the organization will finally confront its toxic past in the spirit of Black Lives Matter.

As Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) gathers for its upcoming annual convention on September 5, it remains unclear if the organization will finally confront its toxic past in the spirit of Black Lives Matter

Abetting the Killing Fields in Darfur

“We will not allow blacks here… This land is only for Arabs!”

New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof reported this chilling quote in a June 2004 dispatch titled “Dare We Call It Genocide?”. Investigating on the ground near Darfur, he cited the testimony of 24 year-old refugee Magboula Muhammad Khattar, who recalled how Sudanese forces had raided her village during fajr prayers. As the soldiers chanted racist slogans, they shot her parents dead. While Khattar fled into the woods with her children, raiders burned the village school and mosque to the ground.

Kristof interviewed another widow, Zahra Abdel Karim, who described how Sudanese soldiers ripped her 4-year-old son Rasheed from her arms and slit his throat. Then the men gang-raped her and her sisters. One of her attackers slashed her leg with his sword and told her: “You belong to me. You are a slave to the Arabs, and this is the sign of a slave.”

While these atrocities were being carried out, Qutbi Al Mahdi sat in Sudan’s Presidential Palace as a senior government official whitewashing mass murder in Darfur for international reporters. When regime forces decimated over 180 Black villages and forced out 18,000 Black refugees, Al Mahdi simply told the Associated Press that Darfur rebels had suffered “a lot of losses.” When George Clooney’s Satellite Sentinel project uncovered evidence of civilian mass graves dug by Sudanese forces, the BBC reported that the regime denied any massacres had taken place – and that Al Mahdi himself threatened to expel international humanitarian aid agencies in response.

Al Mahdi had previously served as the head of Sudan’s internal and then external intelligence service, before merging the two under his command. For his brutally effective work crushing any opposition to the regime, Al Mahdi – despite being a civilian – was accorded the rank of General. As Sudanese troops perpetuated the Darfur genocide, he retained that title as he delivered propaganda to foreign reporters and repressed internal dissidents.

On May 30, 2010, three Sudanese women’s rights activists boarded a plane in Khartoum en route to Uganda for a “Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice” conference organized by the International Criminal Court (ICC). No doubt worried about ICC genocide proceedings against Sudanese regime leaders, Al Mahdi declared that the women’s participation was “a provocation to the feelings of the Sudanese and disregard to their self-esteem, dignity and pride in their national sovereignty.” Before the flight could depart, officers from Sudan’s National Security Service stormed the plane and forcibly removed the women.

While the systemic slaughter of blacks in Sudan was being carried out, Qutbi Al Mahdi, once the President of ISNA, sat in Sudan’s Presidential Palace as a senior government official whitewashing mass murder in Darfur for international reporters.

Leading America’s Preeminent Muslim Civic Organization

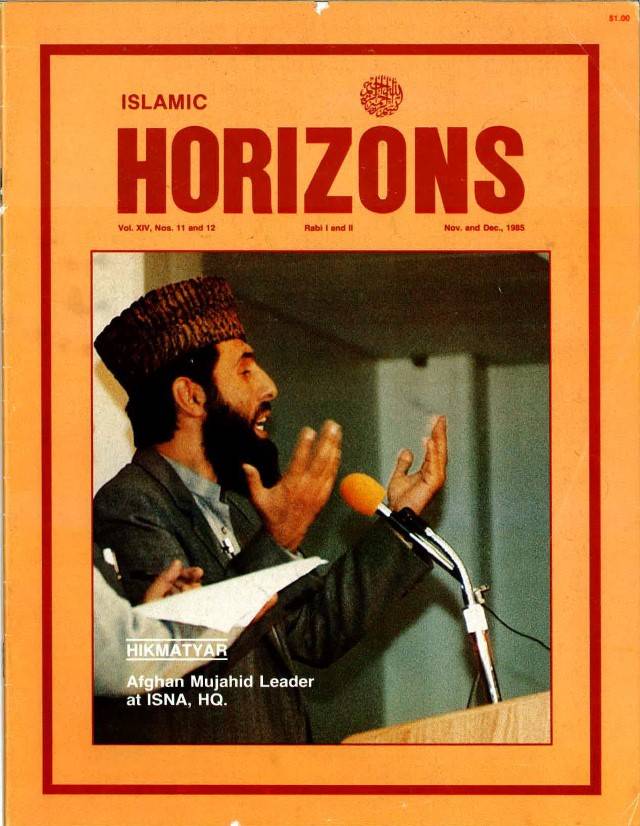

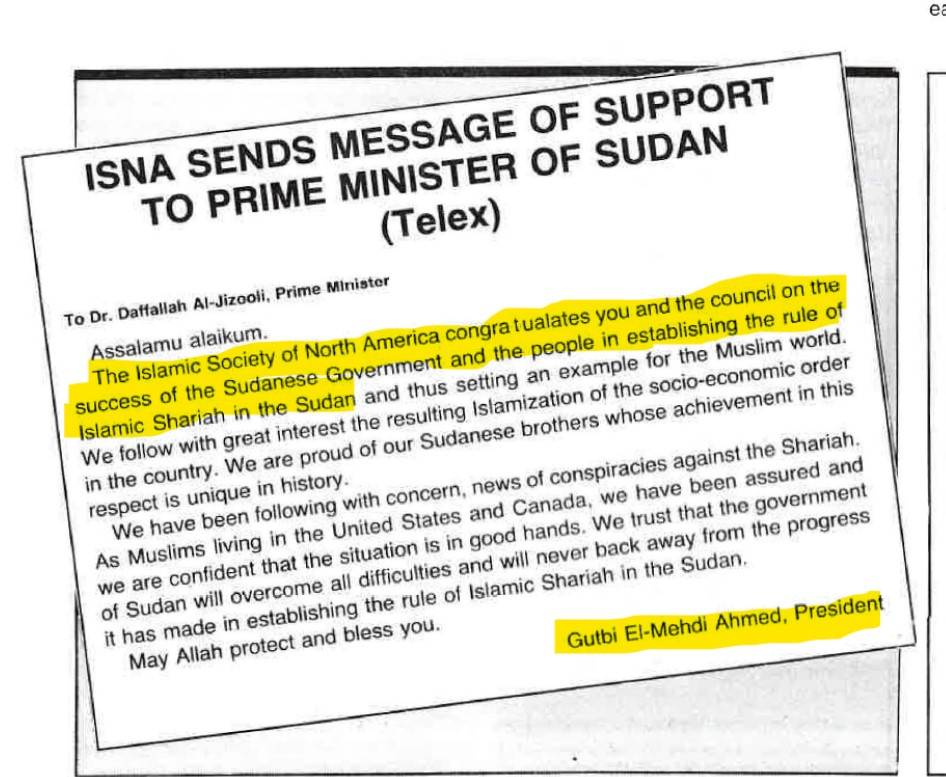

Nearly two decades before the Darfur genocide, the November 1985 edition of ISNA’s newsletter Islamic Horizons featured an unusual letter of congratulations from the organization to Sudan’s new prime minister:

The Islamic Society of North America congratulates you and the council on the success of the Sudanese Government and the people in establishing the rule of Islamic Shariah in the Sudan and thus setting an example for the Muslim world. We follow with great interest the resulting Islamization of the socio-economic order in the country… As Muslims living in the United States and Canada, we have been assured and we are confident that the situation is in good hands. We trust that the government of Sudan will overcome all difficulties and will never back away from the progress it has made in establishing the rule of Islamic Shariah in the Sudan.

The letter was signed by ISNA’s president: “Gutbi El-Mehdi Ahmed.” (The many variations of his name include Gutbi, Gottbi, Qutbi, Mehdi, Elmahdi, and Al-Mahdi). Speaking in the name of millions of American Muslims was the same man who would one day abet a genocide.

Tracing Al Mahdi’s footsteps from Sudan to America and back reveals a path taken by many Islamists from the Arab world in the 1970s. As Professor Steve A. Johnson observes, ISNA’s leadership lay “primarily in the hands of individuals with Islamic movement backgrounds, that is, the Ikhwan al-Muslimun and Jamaati Islami, and who were generally more concerned with the Islamic movements in the countries from which they immigrated.” More specifically, Johnson notes that ISNA’s precursor group, the Muslim Students Association (MSA), “has often been a collaborative effort of Ikhwan members from Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and the Sudan.”

A self-declared “life-long supporter and member” of Sudan’s Islamist political movement, Al Mahdi revealed in an interview with Oumdurman TV that his own father was a Muslim Brotherhood supporter. Al Mahdi studied law at Khartoum University, where he was an Islamic Front leader on campus and got arrested for political agitation. He fled into exile in 1968 and eventually settled in Montreal, earning advanced degrees at McGill University’s Islamic Studies Department. In time, he obtained Canadian citizenship and incorporated the Muslim Community in Quebec as its founding chairman.

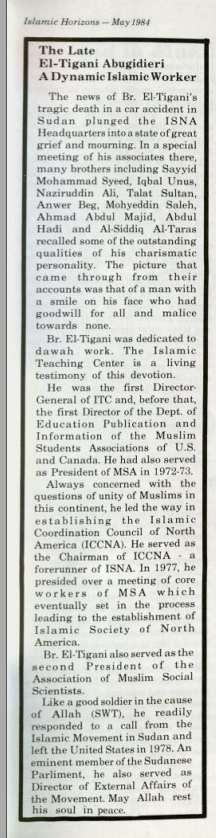

At McGill, Al Mahdi served as a leader in the campus Muslim Students Association (MSA). His fellow Sudanese exile Rabie Ahmed served as North American President of the MSA, a role previously held by another Sudanese Islamist El-Tigani Abugidieri (MSA president in 1972-3). When Abugidieri died in a car crash in 1984, Islamic Horizons published an obituary that noted the ex-MSA president “readily responded to a call from the Islamic Movement in Sudan and left the United States in 1978. An eminent member of the Sudanese Parliament, he also served as Director of External Affairs of the Movement.”

Like Abugidieri, Al Mahdi successfully leveraged the MSA-ISNA platform in North America to elevate his political profile. The April 1978 edition of the MSA’s Islamic Horizons newsletter noted that Al Mahdi helped organize a Toronto Youth Festival for teenagers alongside prominent Muslim Brotherhood leader Jamal Badawi. Al Mahdi likely attended the 1981 annual MSA convention at Indiana University, where Badawi was a key speaker alongside Muhammad Qutb, the young brother of Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb. At the convention, delegates voted to create an umbrella organization called the Islamic Society of North America to meet the needs of a growing community of adults who were no longer students.

In 1982, Al Mahdi was a speaker at the MSA Canada Summer Conference at McMaster University, again alongside Badawi. According to a report on the conference in Islamic Horizons, Badawi lectured to youth leaders about how wives had an obligation to “obey their husbands.” Mahdi and his fellow Sudanese Rabie Ahmed advised parents on the need to help their children “resist the temptations to conform and assimilate.”

A North American Laboratory of Global Islamist Activism

ISNA’s 1982 annual convention hosted an unusual keynote speaker: Dr. Hassan Al Turabi, the godfather of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood. Islamic Horizons reported the title of Turabi’s talk as “Islamic State is an alternative to oppression.” Addressing hundreds of American Muslims, Turabi a Constitutional Law graduate from the Sorbonne, argued that “Islamic movements should at first act in a positive manner with the existing regime” and “only as a last resort should jihad be declared. Once this call is made, however, no effort should be spared to educate the masses in their religion and its principles so they will now exactly why and what they are fighting.”

In 1984, Al Mahdi – by then ISNA’s Vice President – gave the opening welcome at the group’s annual convention. His fellow Sudanese exile Rabie Ahmed stepped down as ISNA Secretary General to return to Sudan, but not before sending ISNA’s formal congratulations to the Sudanese government for establishing Islamic law. The new Sudanese Justice Minister who had spearheaded that breakthrough? Hassan Al Turabi as part of an alliance with Sudan’s then dictator Jaafar Numeri who wanted to secure the backing the Islamist Islamic Front.

As Justice Minister under Jaaffar Numeiri’s regime, Turabi had been diligently implementing the plan for establishing an Islamic state that he had outlined in his speech at the ISNA convention. In a show of force in January of 1985, Turabi had prominent religious reform thinker 76-year old Mahmoud Mohammed Taha arrested for distributing pamphlets opposing Sharia law. Within days, Taha was hanged for apostasy.

Turabi soon returned to ISNA’s annual convention in Indianapolis as an honored guest speaker. Welcoming him at the convention’s formal opening was Al Mahdi, now serving as ISNA’s President. In light of Taha’s hanging, Al Mahdi’s November 1985 letter on behalf of ISNA to Sudan’s leaders takes on a more ideological tone, as it hails them for “establishing the rule of Islamic Shariah in the Sudan and thus setting an example for the Muslim world.” Under Al Mahdi’s leadership, ISNA became an overt ideological support of Sudan’s Islamist regime, cheering on its repressive policies and serving as a launching pad for its ideological vanguard.

Non-Sudanese Islamists within ISNA appear to have become jealous. As Professor Johnson observes: “Splits among Ikhwan factions constituting ISNA became apparent during the 1986 ISNA elections… The Sudanese attempted to rally several groups, including the American Muslims, behind [Qutbi] Mehdi, but they had waited too long and the other faction of the Ikhwan had already launched a telephone and letter campaign to inform fellow Muslim Brotherhood members how to vote.” Raseef22 reached out to Professor Johnson’s

With Al Mahdi voted out of office, other Sudanese promptly lost power within the organization. Johnson reports: “Muhammad Nour, reportedly a member of the Islamic National Front (INF) of Sudan under Hassan el-Turabi, was replaced as chairman of the ISNA Fiqh Committee… Abdulaziz O. Abdulaziz, also allegedly an INF member, was relieved of his responsibilities in the ISNA headquarters.”

No longer top dog at ISNA, Al Mahdi became North America Director of Muslim World League. He ran the organization’s UN office in New York and produced academic studies of the American Muslim community. In a chapter he contributed to an Oxford University Press anthology on “The Muslims of America,” Al Mahdi criticized early waves of Muslim immigrants to America for assimilating and by contrast praised groups like MSA and ISNA for whom “Islam was seen as an ideology, a way of life, and a mission, and the organization was not considered simply as a way to serve the community but as a means to create an ideal community and serve Islam… The real difference ISNA has made in the nature of Islamic work is its assumption of a firm ideological structure and Islamic commitment.”

Decades later, Qutbi Al-Mahdi’s partners still run the show at ISNA. A founding generation shaped by an Islamist agenda, refusing to relinquish power or take responsibility for mistakes – not the least of which were championing Sudan's genocidal regime

Racism as a Tool Wielded by Sudanese Islamists

Everything soon changed for Al Mahdi, as Turabi and his Islamic Front rose to power in Sudan after a 1989 coup dubbed “the Salvation Government.” The growing entrenchment of an Islamist regime in Sudan, led by Al Mahdi’s mentor Turabi, began to make his homeland seem more enticing than North America. “I was in Khartoum by coincidence, and Dr. Al Turabi invited me to a Majlis Shura meeting,” recalled Al Mahdi in a TV interview to explain how he returned from exile.

As Turabi guided the creation of a police state and established militia forces made exclusively of Islamic Front members to crush popular any dissent and establish ideological supremacy of the Islamic Front, this process had a name “Al Tamkeen” or consolidation. Al Mahdi joined the ruling regime. His first served as Ambassador to Iran, absorbing insights on how that clerical regime upheld its rule via loyal Islamist militia. He returned to Khartoum and consolidated control as head of both internal and external security forces, including overseeing a VIP guest of the Sudanese regime: Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who was based in Sudan from 1991 to 1996

Now officially “General Al Mahdi” by virtue of his position atop Sudan’s all-powerful intelligence service, the former ISNA President helped secure a full-fledged police state where prisoners were kept and tortured in secret prison “Ghost Houses” and thousands of civilians were forcibly conscripted in the name of Jihad to fight in southern Sudan and the Nuba Mountains region. The regime’s violence was such that by 1998 it was estimated that over 1.9 million people died in the ongoing war in the South.

As head of the intelligence service responsible for crushing dissent, Al Mahdi could not distance himself from Sudan’s atrocities. In 1998 The National Post reported Al Mahdi was being investigated by the Canada’s Immigration and the Canadian War Crimes Unit for his role in the regime’s atrocities. At the time, Sudanese regime forces made headlines for brutal raids on villages in southern Sudan, both to beat back a rebellion by Christian and animist tribes – as well as to clear land for oil-drilling.

Then in the early 2000s, Black Muslims in Darfur began agitating against the regime’s longstanding marginalization of their region. While Sudan’s Islamic Front regime ostensibly invoked “brotherhood” bonds uniting Muslims, their totalitarian ideological project struggled to account for Sudan’s diversity. Anyone seen as an obstacle to its fulfillment – even fellow Muslims – was deemed expandable. Invoking systemic racial bigotry in Sudanese society to mobilize militiamen to attack Darfuri villages, the supposed inferiority of Sudan’s non-Arabs helped justify why “uppity” Darfuris to be put back in their place. Hence the militia chants reported by Nicholas Kristoff: “We will not allow blacks here… This land is only for Arabs!”

The tragic irony is that Sudan’s Islamic Front once had many Darfuris in its ranks – who ultimately came to realize that rhetoric about equality and brotherhood was superficial. In the early 1970s, a Darfuri named Daud Bolad was nominated by the Islamist National Islamic Front to be the president of the Khartoum University Students Union – the first non-Arab to hold the position. But Bolad soon realized his path to national leadership was blocked within the Muslim Brotherhood because of racial prejudice, observing: “Even when I go to the mosque to pray, even there, in the presence of God, for them I am still a slave [abd] and they will assign me a place related to my race.”

Al Mahdi and Sudan’s ruling clique exploited such ingrained bigotry to terrible effect. The brutal repression of hundreds of thousands of Black Darfuris – including gang rape – would not have been possible without their incitement and encouragement.

Hind Makki, a prominent Muslim American speaker originally from Sudan, recently recounted to AP that as a young student, at the Islamic school she attended, some casually used the Arabic word abeed (meaning “slaves”) to refer to Black people

ISNA’s Old Guard Leaders Like “Confederate Statues”

Thanks in part to Nicholas Kristoff’s reporting, the Darfur genocide became a cause célèbre in America. At a 2006 rally for Darfur on the National Mall in Washington DC, Senator Barack Obama spoke alongside George Clooney as a crowd of thousands chanted “Not on our watch!” The growing movement to stop genocide in Darfur posed a dilemma for ISNA, which had for years been cheerleading the National Islamic Front in Sudan. Staying silent was not an option.

Yet rather than disavow their past cheerleading for the Sudanese regime, ISNA’s leaders offered to help “mediate” the conflict. They released a joint statement on Darfur along with prominent groups like the Council of American Islamic Relations (CAIR) and the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC). The carefully-worded statement never directly addressed racism against Black Muslims by the regime, instead balancing critiques of the government’s actions and the Darfur rebels. It noted that the US government’s official finding of “genocide” was disputed and warned against “politicizing” the Darfur conflict. With their former president Qutbi Al Mahdi trying to spin reporters in Khartoum, ISNA’s leaders in the US did their best to help without damaging their reputations in America.

Many of ISNA’s top leaders today are the same leaders who ran the organization back in the 1980s alongside Qutbi Al Mahdi. Sayyid M. Syeed, a former MSA president and founding ISNA board member, is the current President of ISNA. Another ISNA co-founder and past president Muzammil Siddiqi is the Chairman of the ISNA’s Fiqh Council. A third co-founder, Iqbal Unus, who held the position of ISNA’s Secretary-General when Al Mahdi served as president, still serves on ISNA’s board. Raseef22 reached out to ISNA but did not receive a reply.

Four decades later, Al Mahdi’s old partners are still running the show at ISNA. A founding generation shaped by an international Islamist agenda, they refuse to relinquish power or take responsibility for their mistakes – not the least of which were championing a genocidal regime in Sudan. Their continued control is certainly a boon for Islamophobes, who delight in exposing Muslim community leaders’ ties to extremism.

But in the era of Black Lives Matter, their continued hold on ISNA seems even more detrimental, as any connection to anti-Black racism is highly toxic for Muslim leaders. A recent NBC News report on racism inside the Muslim community noted that ISNA’s “current elected board of 10 directors has no African Americans.” Many are the same old guard from 40 years ago, like statues of Confederate leaders – only still alive and still in control.

Racial discrimination runs deeper than mere governance at ISNA. Hind Makki, a prominent Muslim American speaker originally from Sudan, recently recounted to the Associated Press that as a young student, she would call out others at the Islamic school she attended, some casually used the Arabic word abeed (meaning “slaves”) to refer to Black people.

ISNA meets for its annual convention on September 5 under the theme “The Struggle for Social and Racial Justice.” But while the Sudanese people ultimately rose up last year to throw off the National Islamic Front regime via peaceful protests, the question is whether ISNA’s members will finally remove the tainted leaders, men with direct ties to genocidal racists.

It may be too late to save the hundreds of thousands of Black Darfuris buried in mass graves. But it is not too late to hold Al Mahdi and his American Muslim allies accountable.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!