Since president Sisi’s first term in office, Egypt’s government has emphasised the dual threats of terrorism and fourth generation warfare and what they imply to the security of Egypt and its economic development.

Whilst terror organisations have conducted painful attacks against civilians, vital state infrastructure, and troops in Egypt over the past seven years, the threat of fourth generation warfare is of equal footing—if not more dangerous, despite its apparent material elusiveness. According to the Egyptian president, this is because fourth generation warfare is principally concerned with creating instability in countries by turning their own populations against state through the propagation of rumours and lies as part of larger information or psychological operations.

To raise awareness of this ostensible threat, the Egyptian government eagerly promoted the dangers posed by this new type of warfare throughout state controlled media, children’s educational material, conferences with the country’s youth, and even in religious sermons provided by the ministry for Islamic Endowment. When under scrutiny in foreign press or by rights organisations, the government has continually referred to fourth generation warfare theory to discredit critics and to justify its repression of civil rights and independent journalism in the country through the censorship of political activists, media organisations, and content government ministries deem to be morally objectionable or capable of undermining state authority.

Egypt’s fourth generation warfare theory is largely a creation of military and security establishment academies and colleges. These ideas first gained traction with national security specialists following the 2011 Egyptian revolution and since then have become a principal part of courses run by these institutions for senior staff and regime officials. Regularly producing research that was conspiratorial and prone to dogmatic anti-western thought before the Arab Spring, the adoption of fourth generation theory has allowed both officials and security agencies to reproduce and present these sentiments as proven academic fact.

Outside Egypt, since the late 1980s, scholars and analysts had typically used the term as a descriptor for decentralised or hybrid conflicts prevalent during the Cold War in which state actors utilised guerrilla like proxy forces in concert with sophisticated information operations and psychological warfare to destabilise and potentially defeat an adversary rather than conventional military force. More recently, fourth generation warfare theory has seen a return in popularity after the Russian use of deniable troops and proxies to invade Ukraine and its use of influence operations against predominantly western democracies that oppose Putin.

This theory’s greatest flaw however, is that hybridity in itself does not fundamentally change the way in which wars are actually fought, rather it is an expression of power asymmetries or imbalances between foes that require the use of unconventional strategies and tools to fight within particular (often isolated) domains to avoid potentially disastrous head on collisions with superior forces. As such it does not represent a true departure from the third or industrialised generation of warfare which has influenced every facet of how we fight since the Great War on a basic level.

Regularly producing research that was conspiratorial and prone to dogmatic anti-western thought before Arab Spring, the adoption of Fourth Generation Theory allowed officials and security agencies to reproduce and present these sentiments as proven facts

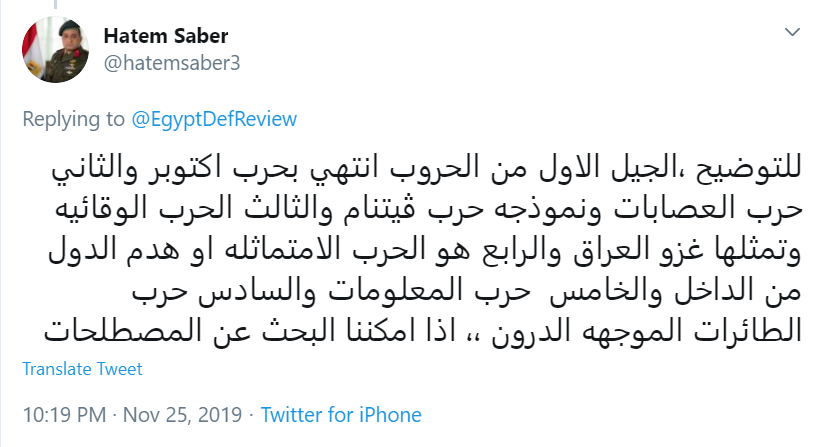

The Egyptian concept of this theory however is riddled with additional flaws that muddle military strategies, technological advancements in support arms, and political policies with generational leaps in how we fight. This confusion has led to various Egyptian government officials and national security experts defining both past and future methods or generations of warfare based on their own (often conspiratorial) perspectives without reference to evidence or academic research. Egypt’s centre for Sunni scholarship, Al-Azhar University, has used its own conception of fifth generation warfare to emphasise the corrupting threat social media presents to the country’s religious identity and the need for greater censorship to tackle content it views as morally objectionable. Education officials and state linked news media organisations have also used the definitions to promote conspiratorial speculation over weaponised climate change as a potential threat and have boosted voices which claim the novel coronavirus is a bioweapon manufactured in the United States. The national security lecturer at the Nasser Higher Academy and former commander of Egypt’s infamous military hostage rescue force retired. Lt. Col Hatem Saber based his definitions on largely random characteristics which include incremental technological improvements, political policy, and differing strategies whilst failing to prove the existence of distinct, separate, or successive generations of warfare. The October war was by no means the last conventional conflict nor Vietnam the first-time guerrilla strategies and tactics were used against a great power.

Information operations which feature prominently in fourth generation warfare have been part and parcel of conflicts since the invention of the printing press.

Egyptian fourth generation warfare then combines the fundamental flaws of the original theory with a deluge of conspiratorial and anti-western sentiments in order to manufacture threats to justify its continued repression and the expansion of its censorship and surveillance activities to online content and political spaces. The manufacture of these threats have also presented a convenient scapegoat to excuse state failures such as the fall of the Mubarak regime and the military’s struggle against militant groups across the country by arguing that they are principally the result of foreign plots to undermine the country’s stability and security services rather than popular revolutions or institutional failures. Furthermore, these generational definitions have been used in state media and by security experts to praise the military’s extravagant arms build-up which introduced new equipment such as military communications satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles as generational leaps in warfare capability, despite the proliferation of similar platforms around the world for more than half a century.

Whilst 4th Generation warfare theory as a whole suffers from a lack of credibility, its protection from scrutiny has led to a situation where it has been enthusiastically adopted by president Sisi as justification for a brutal crackdown on critical voices

So whilst fourth generation warfare theory as a whole suffers from a lack of credibility, its protection from scrutiny has led to a situation where it has been enthusiastically adopted by president Sisi’s regime as justification for a brutal crackdown on rights and critical voices. Accused of detaining tens of thousands of political prisoners and exercising control over the country’s media landscape, the Egyptian government often claims it is merely responding to foreign enemies intent on destabilising the country from within by promoting rumours and creating societal divisions. This narrative has seen some success amongst a general public that is often prone to conspiratorial theories and anti-western sentiment.

This academic incoherence involved in this issue has become par for the course within Egyptian military and security higher education establishments, most of which are primarily concerned with training active duty personnel for staff appointments and senior command positions. Staffed by retired officers and closed to the general public and wider academia, these institutions continue to produce research and theories that are absent from critical peer review or general public scrutiny. This situation is exacerbated by an environment in which the foundational narratives Egypt’s dominant military establishment relies on to derive political legitimacy are above the prospect of challenge or criticism in order to avoid reputational damage that could undermine trust in the armed forces’ image as a competent and powerful institution with a successful and storied history.

Despite the regime’s attempt to convince Egyptians that the state is under a subversive foreign attack it has only ever replied to this supposed enemy by closing internal political spaces and censoring avenues of dissent

Egypt’s national security academic sectors are unlikely to receive any challenge from any civilian scholars specialised in security and defence matters. Successive regimes have purposefully restricted the emergence of war and security studies departments which could potentially produce research critical of Egypt’s chequered military history and regime foreign policy thereby potentially undermining confidence in the country’s military and security agencies or tarnishing the states’ authority as a whole. The suppression of these departments has also allowed the country’s security institutions to hoard discipline specific knowledge away from the public and the rest of the civil service which allow them to claim unique expertise that cannot be criticised by non-specialist members of the public or opposition activists. Even scholars of other disciplines with research proposals that could explore the role of Egypt’s military and security agencies in fairly mundane areas are routinely denied by politicised university administrations and faculties that tend to self-censor in fear of potential punitive action or that are convinced that security agencies should remain above reproach.

Despite the regime’s attempt to convince Egyptians that the state is under a subversive foreign attack it has only ever replied to this supposed enemy by closing internal political spaces and censoring avenues of dissent. Successive media campaigns deriding the United States, Turkey, or Qatar for instance have only ever picked up traction inside the country and often rely on the propagation of mis or disinformation through government linked personalities and bot networks. Analyses of these trends often highlight how these rather transparent influence operations are largely targeted at the Egyptian public rather than any actual foreign rivals.

In fact if fourth generation warfare theory is to be uncritically believed and security agency information operation patterns are taken into consideration the Egyptian state appears to be at war with its own public rather than any foreign enemy. While the government may claim that is closing political spaces and cracking down on civil liberties to combat rumours and discord, the adoption of fourth generation theory has allowed them to widen regime securitisation initiatives beyond their traditional avenues or methods of repression. The manufacture of threats and reliance on state propaganda to disparage regional rivals and to whip up public support may bring short term domestic gains in terms of policy popularity but may eventually create counterintuitive animosities that restrict foreign policy decisions, act as obstacles to eventual rapprochements with supposed rivals, undermine bilateral relations with allies such as the United States, scapegoat essential services, and perhaps more importantly divert attention away from actual and pressing national security threats at home or abroad.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!