Five years ago, my husband and I went on a weekend road trip to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCa), one of the largest collections of modern art in the United States, housed in a converted factory complex in North Adams in the northwest of the state. We were joined by two friends – a mother and daughter – both sharing the name Philae. I don’t believe in coincidences and here’s one reason why.

Philae is the Greek name given to an island based in the reservoir of the Aswan Low dam. It was the site of an Egyptian temple complex dedicated to the goddess Isis, where an ancestor of the two women had been involved with an archeological dig when that was the sort of thing British colonial officers did. The ancient Egyptians believed the island was one of the burial sites of the god Osiris, king of the underworld. Now keep all that in mind because it is relevant to this tale.

The day after our visit to MASS MoCa, the four of us continued to the Clark Museum in Williamstown. Following that, we decided to visit nearby Williams College where we stumbled upon an exhibition at the school’s art museum showcasing works by Fathi Hassan entitled “Migration of Signs”. Hassan is an Egyptian-born Nubian artist who works in mixed media and explores the ambiguity of language serving as allegories for events such as the Arab Spring, now a distant memory, and the displacement of the Nubian people.

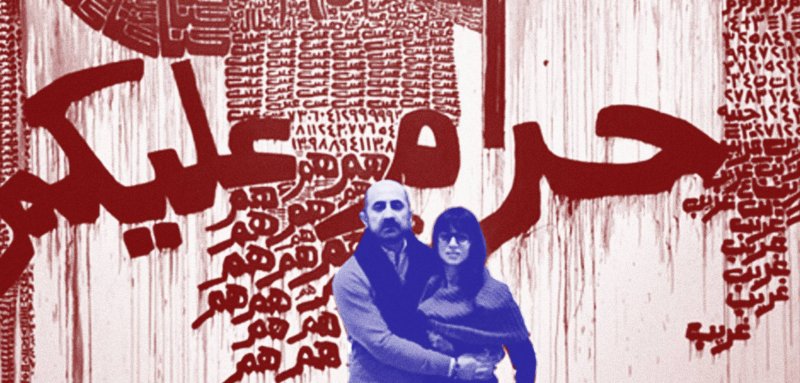

Egyptian born Nubian artist Fathi Hassan's exhibit entitled “Migration of Signs” explores the ambiguity of language serving as allegory for events such as Arab Spring, now a distant memory, and the painful displacement of the marginalised Nubian people

Nubia is a region extending from south of Aswan to Khartoum in central Sudan, and its indigenous people represent a distinct ethnolinguistic group with a language unrelated to Arabic. Known to the ancient Egyptians as “the Land of the Bow” for the inhabitants’ prowess in archery, Nubia was the seat of one of the earliest African civilizations. After its temporary absorption into Egypt’s New Kingdom 3,500 years ago, Nubians provided the empire with military leaders and several Pharaohs. And lots of gold.

The region’s history is complex, but let’s fast-forward a few millennia to the middle of the century when the Great Aswan Dam was built. When Lake Nasser was created in the sixties, flooding 5,250 km2 of land, many Nubians were forcibly displaced, their villages and farmland now underwater. While we all remember the epic relocation of the great Abu Simbel temple complex, the history books largely overlook the less heroic forced migration of an entire people. The loss of traditional lands and the government’s failure to fulfill their promises of adequate compensation is probably the central issue of Egyptian Nubians today. The marginalization of their culture – conveniently put on display to paying tourists visiting the ruins of Luxor and Aswan in the form of folkloric song and dance shows – and the apathy of the government towards protecting and supporting their language is an ever-present complaint echoed in Hassan’s work.

Much of the art on display deals with this gaping loss and most of his canvases are painted in somber black and white. Haram aleikum (shame on you) is painted across a large canvas. The text is often intentionally indecipherable Arabic calligraphy, a metaphor for his people’s unheard or ununderstood voices. More care and money were expended in the moving of the temples than on the resettlement of the Nubians, but Hassan’s art helps ensure that the passion behind the words doesn’t get lost like forgotten languages on the side of an obelisk.

Early during the COVID lockdown, I happened to see Hassan’s name attached to an Instagram talk and I quickly jumped at the chance of signing up. Following his chat, we quickly began an epistolary friendship, using technology to our advantage, graduating from text to voice to regular Facetime calls. I have immersed myself in his work and find it filled with nostalgic references to his early formation as well as to an ear that seemed filled with more hope.

It was here in America that I discovered the history of Nubia, and now it seems that history is changing – or at least being revised – with respect to the treatment of black people and other ethnic minorities, sparked by a single incident in this country that lit a tinderbox replete with other wrongs. Around the world, protests have rung – some peaceful and some less so – questioning the historical role of non-white people in our societies and the appropriation of their culture to conveniently fit the stories with which we grew up. Now more artists like Fathi Hassan are needed, to shine a light on the injustices committed against those whose histories are less known and whose voices seem distant.

Here in America the lockdown has driven the Lebanese/Palestinian/American photographer Rania Matar to exit the cocoon of her home and use her camera to capture images of women (and some men) sheltering in place, through the shield of their windows and doors. As Rania wanders the streets of her hometown of Boston with camera in hand, she captures Sophia and Lucy, two sisters standing behind their glass front door. They pose in an intimate and loving way with one sister resting her chin on the other and sister’s shoulder, with their hands reassuringly held together.

It's here in America that I discovered Nubia's history, and now it seems that history is changing – or being revised – with respect to the treatment of black people, sparked by a single incident in USA that lit a tinderbox replete with other wrongs

Another image is of Fernanda, a flamenco dancer wearing a garishly pink dress pictured in profile with her sinewy right arm raised and resting on the glass-paned door. The window becomes her stage. Rania is the lone audience member capturing a moment in time where performing has been halted. It is nevertheless a hopeful image. In the words of Rumi “If the house of the world is dark, love will find a way to create windows”. There will be performances in Fernanda’s future, but for now we must wait patiently and remember the ever-present risks of a resurgence.

Before signing off, I would be remiss in not mentioning the death of a giant in Egyptian art who left us this month. Adam Henein was an Egyptian sculptor born into a family of silversmiths. He was one of the last of the first generation of Egyptian artists who emerged in the 1950s in the wake of Egyptian nationalism and a rekindling of pride in their cultural heritage. In the late 90s he headed the design team involved in the restoration of the Great Sphinx of Giza. He would weave modern interpretation of universal themes such as freedom, faith and motherhood with Egyptian icons such as obelisks, ancient gods, and hieroglyphics. He worked mostly in bronze, clay and granite but also painted, primarily in a style that drew on his heritage in abstract and representational art. He was known for his animal forms, with the bird having a special place in his heart.

“We see the bird throughout his career. It kind of symbolizes freedom, movement and trying out different things,” notes Curator Sheikha Noora Al Mualla writing in Arab News when a retrospective of his work was held in the U.A.E.’s Sharjah Art Museum in October 2019. His birds, whether sleeping or standing, seem vulnerable. He was fascinated by the liberating act of flying.

Allow me to leave you with the words of J.M. Barrie the creator of Peter Pan: “The reasons birds can fly and we can’t is simply because they have perfect faith, for to have faith is to have wings.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!