Walking down Charles Malek Avenue, I go down a familiar path I’ve taken many times since the uprising began on October 17. The road leading from my Geitawi apartment to downtown Beirut, the heart of the Revolution, took the form of a pilgrimage route over the precding weeks.

Except today, I’m not a lonely walker: as I leave the calmness of my neighborhood, the sound of sirens fills the air with the sound of screaming fear. As the ambulances run next to me, I can’t distinguish any of the Red Cross flags, usually prominently displayed. As if, I think to myself, they were already at half mast, mourning for the 377 people they will carry back to hospital that night.

Saturday saw the crowning of the week of Anger with a night of blood.

As I continue my descent into the narrow streets that surround Martyr’s square, my body melts into a cloud of tear gas. The closer I get to what seems to be the eye of the storm, the more I get the feeling of entering a cold water lake: as my breath is cut by gas and my blood flow accelerates, I immerse myself in a sea of unquantifiable violence.

Since when was the Lebanese identity incompatible with the exercise of physical violence against compatriots? Will the respect for Lebanon’s army last much longer?

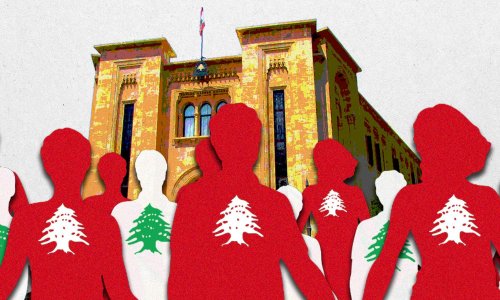

Up to the fairly distant Beirut waterfront, hundreds of silhouettes dressed in black are facing uniforms. Each rubber bullet is followed by a stone, as if three months of protests had set us all up to be a well-honed choir performing a timeless song. That of repression.

A song that I know too well, as I was breaded by the social movements that shaped my hometown of Montreal in the last decade. From the 2012 student strike to the anti-austerity protests of 2015, my teenage years were forged in the streets, by the unforgettable lesson of paving stones and batons. I was a good student, and still today my body carries the memory of fear when I face a police officer or one of his rubber vassal.

When the Lebanese Revolution first broke out, it was complicated mental gymnastics for me to hear the protesters praise the army in their chants. Soldiers were called Watan, Arabic for nation, and the only other unifiying flag, apart from the Lebanese one, was the army’s. Not only was I filled with visceral rejection of the state-power they represented, but also could I feel the mere nationalism that consumes every nuance in this country’s political landscape. Al watan.

The Lebanese Armed Forces are not a theoretical exception to the rule of state monopoly on legitimate violence. Though in practice, their monopoly is highly threatened by the financial and military force of the pro-Iran militia Hezbollah.

80,000 strong, the Army managed to maintain a highly respected position with a large majority of the Lebanese population. Even after the fifteen year Civil War (1975-1990) and nearly 30 years of Syrian military occupation, most people see in them the only institution free of corruption and the sprawling hand of sectarianism.

When the Lebanese Revolution broke out, it was complicated mental gymnastics for me to hear the protesters praise the army in their chants. Soldiers were called Watan, Arabic for nation, and the only unifying flag, apart from #Lebanon's, was the army’s.

As I recognize a friend’s eyes under layers of dripping eye-liner and a scarf, she reminds me of a fundamental distinction that regulates the growing hatred of demonstrators towards the armed officials: “ The real dogs are the cops,” she says, pointing to an ISF (Interior Security Forces) member with a contemptuous spit, “the counter-revolutionaries keep saying that our movement is financed by Israel and other foreign powers, but I can tell you that with the way the police treats us, I’m starting to doubt if they’re really Lebanese.”

Projected once again in history, I reflect on this last bit of sentence, that escaped my friend’s lips between two sighs of exhaustion. Since when was the Lebanese identity incompatible with the exercise of physical violence against compatriots?

As this thought crosses my mind, I follow a group of Shabab (young men) to a side-street for a cigarette break, sheltered from flash bombs that keep raining from Beirut’s sky, terribly used to these seasonal outbursts.

Next to our unlikely troop, in which my blondness certainly clashes with the hardened faces of anger and despair surrounding me, soldiers are gathered around a half-empty packet of Lucky Strike.

For the first time since October 17th, I notice that all of the soldiers faces are covered. Only a couple of meters away from us, ten hooded heads are repelling tear gases with each exhalation of smoke. At this precise moment, they are an exact mirror of us: fragile beneath their armors, bending to the imperatives of nicotine in a commonly shared ritual.

Thousands of times have I seen a soldier releasing his boredom in the length of a cigarette. In Lebanon and its capital, they are posted at the corner of every street. Nobody really knows why, nor do they try.

I remember a conversation with an Army officer. Stepping out of the role that his uniform implies, he was telling me about the political-will behind the sometimes overwhelming presence of useless soldier: “ The state consciously employs young men from the poorest areas of the country and gives them guns for them not to revolt, ” he said, reminding me that the unemployment rate reached almost 24% of the Lebanese youth in 2019.

From Akkar to Bint Jbeil, young men from the underprivileged regions of Lebanon are now used as human shelters by the political parties. Between the Grand Seail, the goverment’s Ottoman era seat, and the streets it looks down on, the soldiers’ bodies are used to feed both insatiable greed and the hunger for justice.

By definition, I remind myself, the function of a mask is not only to hide its wearer’s face, but it can also serve as a representation of something he is not.

Inexhaustible soundtrack of the last days, sirens continue their lament. I don’t know it yet, but that night the number of people injured in the streets will reach its peak.

"Yalla, it’s time to go back!" shouts one of my companions, a surprisingly tall teenager that came all the way from the northern city of Tripoli. The others are still putting their gear back in place, reaching for onions in their pockets and gas-masks on their foreheads, for the most still spared by the passage of age.

A drag of water away from going back to what seems tonight like a frontline, I take one last look at the soldiers. In a glance, I notice one of them nibbling on the straw of a Bonjus, Lebanon’s most popular juice brand.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!