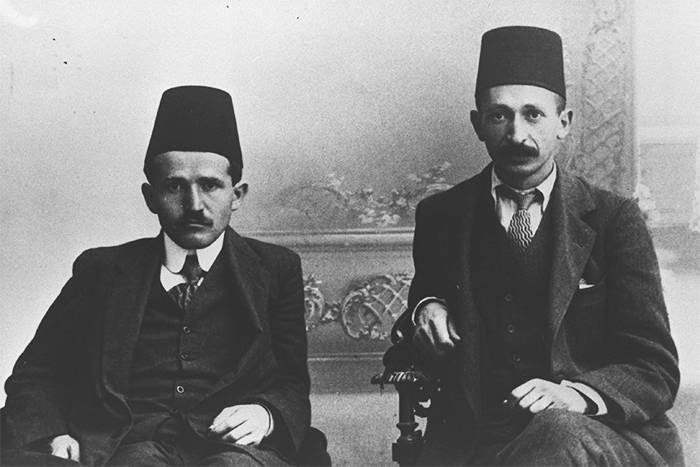

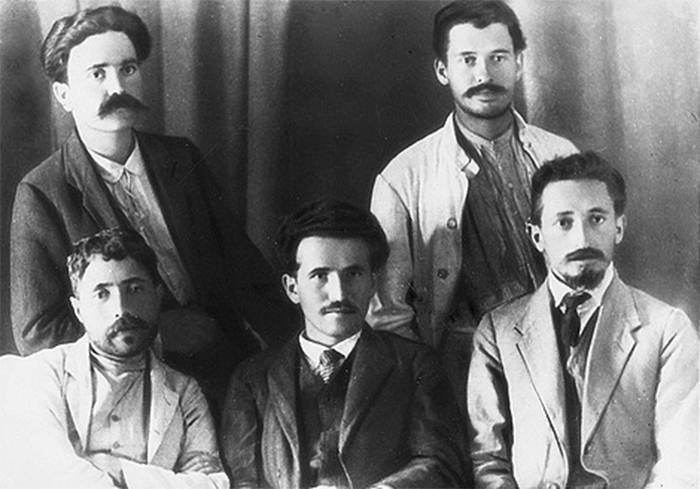

It will probably come as a shock to many that the founder of Israel, David Ben Gurion, lived some of his most formative years in Turkey - a period in which he developed his character, honed his identity as well as his cultural, educational, intellectual, social and political foundations. This period in Ben Gurion’s life reveals to us many important secrets, firstly surrounding the personality of Ben Gurion, and secondly on the concept of Zionism during its early stages - especially as held by the major figures of the Zionist movement who would go on to participate in the foundation of the State of Israel, such as Ben Gurion - Israel’s first Prime Minister - and his friend Yitzhak Ben-Zvi - one of the major figures during the foundation of the State and Israel’s second and longest-serving president. Perhaps the most peculiar development was the discovery by Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi of Zionism while living unde Ottoman rule - for the duo’s aspirations were inextricably linked to loyalty to the Ottomans and Ottoman society, which they loved and defended like any other Ottoman citizen - regardless of their religious, national or ethnic affiliations.

While it may no longer be possible to politically build upon this discovery - with the suitable moment for that having long passed - it nonetheless was an important matter in Ben Gurion’s time and era during the early twentieth century: for it is probable that the Zionist project at that time was not planning to create a separate state independent from the Ottoman Empire, but a social and collective state, or a refuge or sanctuary specific to Jews which could offer them a safe haven to escape the persecution they encountered in both Eastern and Western European states. The most important aspect of such a project was for Jews to become Ottoman citizens, no longer holding Russian nationality or that of some other persecuting state. If so, the trajectory of the Zionist movement could have been significantly altered if the conception of Zionism as held by Ben Gurion and his likes was contained by the Ottoman state: for at the time, these figures preferred cooperation with the Ottoman state over seeking support from the English and French.

David Ben Gurion was born in the Polish province of Płońsk on the 16th of October 1886 - then part of the Russian Empire. He immigrated to the Ottoman Empire in 1906, and to Ottoman Palestine in the same year, before moving to Thessaloniki on the 7th of November 1911 - then also part of the Ottoman Empire - inhabited by Muslims often referred to as “Dönmeh”, Jewish converts to Islam as well as Jews who were said to have privately retained their original faith. There are few details on the life of Ben Gurion in the Ottoman Empire during his early years there, but it is likely that one of the main reasons for his migration was the persecution faced by Jews in Poland, Russia and Eastern Europe (as well as Western Europe) at the time. Ben Gurion’s father, Avigor Grün, also had an influence on Ben Gurion’s development, having worked as a lawyer and leader of the ‘Hovevei Zion’ (“Lovers of Zion”) movement in Płońsk - to add to Ben Gurion’s own aspiration to find a country in which he could enjoy personal liberty and religious freedom in. Russian authorities had twice arrested Ben Gurion as a student at the University of Warsaw in 1905 for his Zionist-Marxist activities that had begun a year earlier; thus his migration to the Ottoman Empire resembled an act of political asylum, with Ben Gurion testifying to its amity, forgiveness and religious freedom for non-Muslims.

Accordingly, Ben Gurion aspired to make the Zionist movement dependent and loyal to the Ottoman Empire, also requesting the same of his fellow Jewish friends at the time. Perhaps the most surprising fact was his voluntary enlisting in the Ottoman army in later years, considering himself an Ottoman citizen; here, Ben Gurion even sought to volunteer in an Ottoman garrison that was defending Jerusalem from the occupation of the British Army during the First World War, as several Israeli historical sources attested (notably the memoirs of Asray Avant Israel). Yet the Jewish migration to the Ottoman Empire was not only out of a state of emergency, but had been a continuous occurrence since the establishment of the Ottoman state - especially following the persecution that both Muslims and Jews suffered after the reconquista of Muslim Spain. Indeed, 2,000 Jewish families were estimated to have been resettled in the Middle East during the reign of the Ottoman sultan Bayezid II, where they found security, tolerance and religious freedom amongst Muslims. After his arrival at Thessaloniki, Ben Gurion took immediately to learning Turkish at the hands of a Jewish teacher, before working in journalism whereby he sent his articles to outlets that supported the Zionist cause in Palestine. Ben Gurion would then enter Istanbul University in 1912 to study law, a degree he completed two years later. Following his studies, Ben Gurion would take to travelling between Turkey and Palestine, before finally settling in New York in 1915, marrying and giving birth to three children.

Following the Balfour Declaration in 1917, Ben Gurion enlisted in the British Army a year later, in the 38th Battalion of the Jewish Legion in Palestine - where he would establish armed Zionist gangs to fight Palestinians. Ben Gurion would be the one who read out Israel’s declaration of independence on the 15th of May 1948, serving as the first Prime Minister and Minister of War in the first Israeli cabinet - remaining in the country’s circles of political authority for more than fifteen years until 1963, finally passing away on the 1st of December 1973.

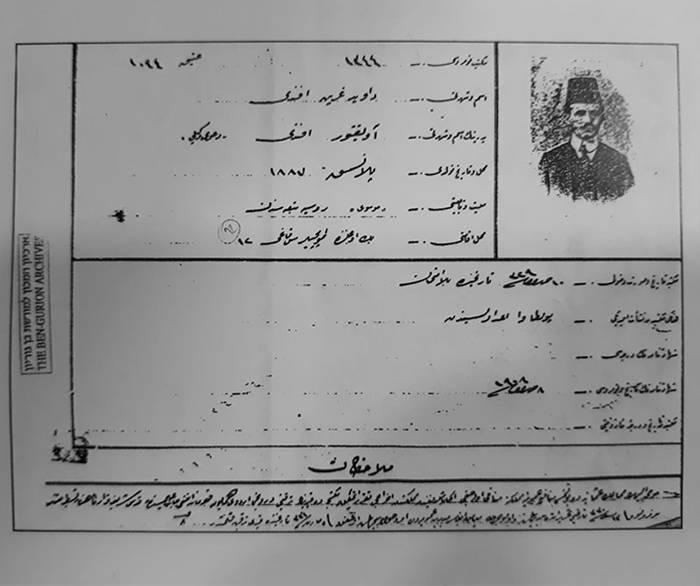

During his years of study at Istanbul University, Ben Gurion resided on Topçekenler street in the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul near Taksim Square, where he lived with his friend Ben-Zvi. His address was discovered on his University ID card, as Ben Gurion received his residence and studying permit from the government of Istanbul. There is little doubt that this period would bear witness to monumental events in the history of the Ottoman state, as comprised in the foundation period preceding the declaration of the Turkish Republic after the end of the Ottoman Empire on the 30th of October 1923. Ben Gurion’s records in the Faculty of Arts of Istanbul University were listed as follows:

Record Number: 1244

Name: David Gurion Effendi

Father’s name: Avigdor Efendi

Place and Date of Birth: Plonsk, 1887

Ethnicity and Nationality: Jew from Russia

Amongst the important events that attracted the attention of researchers was Ben Gurion’s interest while in Istanbul in the Second (Ottoman) Constitutional Era in 1908, following the deposing of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. During this period, Ben Gurion considered the Jewish representatives in the Ottoman parliament as unrepresentative of the community, and so proceeded to learn Turkish in order to participate in parliamentary elections. Similarly, Ben Gurion was surprised to find that most law students in Thessaloniki worked in industry and in the port as seamen, later writing: “I did not see a Jew doing physical labour, and so began learning Turkish from a Jew in Thessaloniki.”

Ben Gurion would succeed in his task to learn the language within a few months, and his teacher invited him to Zionism - an invitation which he accepted. Ben Gurion thus entered politics without wasting time, and began to follow and monitor Ottoman newspapers after having learned Turkish, while also contributing his own writing and sending articles to various Zionist publishers and printing outlets that were present in Palestine. After spending an entire year in Thessaloniki, Ben Gurion decided to travel to the heart of Ottoman politics in Istanbul with his friend Yitzhak Ben-Zvi; the entry requirements of Istanbul University during this period required passing a test in Ottoman Turkish as well as Ottoman literature, geography, history and pre-law.

Ben Gurion enlisted in the Ottoman army, considering himself an Ottoman; he sought to volunteer in an Ottoman military garrison defending Jerusalem from the occupation of the British Army during World War I

Ben Gurion the Ottoman to the world Jews: “O dear Jews, do not be deceived by the English and the French, who talk of democracy and equality; they are honest but only insofar as it pertains to themselves, they did not grant any equality in their colonies”

The director of the law school was the individual in charge of organising the entry of students into these examinations - yet he could not believe that Ben Gurion had succeeded in learning Turkish in eight months, and he congratulated him for his efforts and hard work. Ben Gurion would succeed in passing the examinations, but further difficulties awaited him: namely, that the Turkish government imposed a requirement on university students that they enter military service first before entering university. Yet Ben Gurion was able to solve the issue, before coming against two further problems: namely, obtaining a permit to study and live. Again however, Ben Gurion was able to solve the two obstacles through employing a local lawyer.

At the time, the First World War was iminent. Ben Gurion noticed that Ottoman soldiers, despite their exertion in war, did not deploy their frustrations against the people in Istanbul, by contrast to his previous experience and observations of Russian troops. He thus became convinced that the news he used to hear of Turks while in Russia were false, proceeding to take it upon himself to respond to the false allegations circulating around Turks by declaring:

“When we read the Russian newspapers we were much surprised when they said that the Turks oppressed the Christians in Istanbul, to the degree that they cannot even go to the streets; in reality, tranquility and security prevailed across the city despite the transit of thousands of soldiers through it on their way to the frontlines. I did not witness such a scene in Russia where soldiers pass through the markets of Istanbul without causing any damage; the situation was very different in Russia, whereby the soldiers vented and emptied their anger at the people when passing through the markets, with blood spilt of these Russian soldiers who are described by Russian newspapers as tough and savage on the frontlines.”

Meanwhile, when Ben Gurion saw that medical students were sent to the frontlines to treat the wounded, and engineers to build bridges and railways, he asked himself: “What can law students and lawyers offer for the war?” When the number of wounded amongst university students began increasing, Ben Gurion began feeling tense and anxious that he would not be able to finish his studies in Istanbul, and so departed to Palestine for a while before returning to Istanbul in March 1915, departing from Haifa and passing through Beirut. Yet the war would continue at a lightning pace all over the world, prompting Ben Gurion to describe Turkey’s reality during these years in the following terms:

“The Turks continued drinking coffee out of their cups, as if nothing was happening; until now, the university is closed, the ranks are filled with the wounded, and the head of the university is searching for temporary buildings [in the hope] perhaps that the university will open again, but we doubt his ability to find these buildings.”

During these events, Ben Gurion would also write to his father, declaring: “Everything in Turkey proceeds in tranquility and quiet, while pessimism dominates journalism and the media, and fears have begun after the people have become assured that the Roman [European] provinces have been lost, and these fears have increased with the loss of the Arab provinces, out of fear that a new caliphate would emerge in these regions.”

In April 1913, the universities began to teach in private homes, and Ben Gurion was required to obtain a medical document proving that he was healthy, as well as a document proving that he had taken a vaccination from the government in Istanbul in order for his payment of university tuition installments to be accepted - before falling ill during this period because of the weather and climate in Istanbul.

Before the exams were held in July, Ben Gurion would participate in a conference held in Vienna on Zionism. As for his examination results, he would achieve a full mark (10 out of 10) in civil rights, penal law, administrative law as well as politics, economics and finance, while receiving a mark of 9.5 out of 10 in international law, and a mark of 8 in constitutional law. Ben Gurion’s academic excellence would prompt his penal law teacher to invite Jewish students from Russia to learn and study in Istanbul, after bearing witness to Ben Gurion’s successes. University lectures would finally resume in November, with news of reforms being undertaken in the Law Faculty reaching Ben Gurion through newspapers. Accordingly, the subjects of Roman Law, Philosophy of Law, Contemporary Law and Forensic Medicine (medical jurisprudence) were added during the new academic term. Furthermore, a new Jewish teacher was hired. However, when classes began Ben Gurion would be surprised to find two new subjects that he was unaware of, namely Inheritance and Public Rights.

When Ben Gurion realised that he could not learn Roman law without learning the language (with the subject forming the mainstay and foundation of modern Western law), he asked his father to send him a Russian-Latin dictionary, a book on Latin Grammar, an explanatory guide in Russian and a Latin reading book. Because of his confidence in his French, Ben Gurion would require only a few weeks to learn Latin, passing with excellence his exams in 1914 with full marks in the subject of Islamic law. Exhausted of exams and having fallen sick several times as a result of his inability to acclimatise to Istanbul’s weather, Ben Gurion would travel to Palestine for a vacation with Ben-Zvi - with little awareness however of the wars and displacement that would take place in the area. Indeed, Ben Gurion’s departure from Turkey in 1915 was unlikely voluntary, but probably forced due to accusations aimed at him for participating in Zionist activities in Palestine - which the Ottoman state treated with suspicion, opposition and resistance.

The circumstances of the Ottoman state during its last few years, especially during the First World War (1914-1918) and indeed, even for years beforehand, ensured its failure to realise the dangers of Jewish migration to Palestine either through Turkey or through Ottoman ports (both land and sea). Even if it did know of these migration waves, the state did not realise its dangers towards the future of Palestine, as the Ottoman state considered Palestine first and foremost as part of its territory, thus allowing its citizens to move through and within it without restraints. Accordingly, the migration of Anatolia’s Jews to Palestine and their return to Turkey were considered natural events - despite the religious meanings that the region had for Jews, Christians and also Muslims - but the increasing dangers of the Zionist movement was a subject of sensitivity and prompted many to feel its negative effects.

Jewish students used to travel on a student discount to Jaffa on a Russian ship; on their way to Palestine came the news of the declaration of war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia on the 28th of July 1914 - to be soon joined with another piece of news, the killing of Jim Jors. The next day, Germany would declare war on Russia, and would be joined with the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war in October 1914 - placing the Jews of Palestine in a difficult situation, as most of them were Russian citizens who feared that they would be forcibly displaced by the war.

Subsequently, Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi would undertake a decision for Jews to request Ottoman citizenship as a result of the persecution of Jews in the Russian Empire, to form a Jewish military unit to defend Jerusalem in the event that it came under siege, and for this military unit to train in the garden of one of the Russian churches. After this news reached the Ottoman military commander Djemal Pasha, he ordered the dismantling of the military unit and arrived in Jerusalem. Here, one of the Jewish leaders conducted an interview in French with Djemal Pasha, and the latter would provide the Jewish interviewer with a document written in Turkish to deliver to Ben Gurion. According to Ben Gurion, the deliverer of the message did not understand its contents as he could not read Turkish, leaving Ben Gurion in a state of shock at what was written within it: praise of the Jews and recounting the good treatment by the Turks of the community, while affirming that the Jews in Palestine were Zionists, and Zionists were enemies of the state. The document also declared that anyone who possessed Zionist documents, newspapers or literature in general would be executed. While Djemal Pasha had promised the Jewish interviewer during his meeting that he would not disclose the details of the document, he would however soon publicize and circulate the document in Hebrew in Jerusalem.

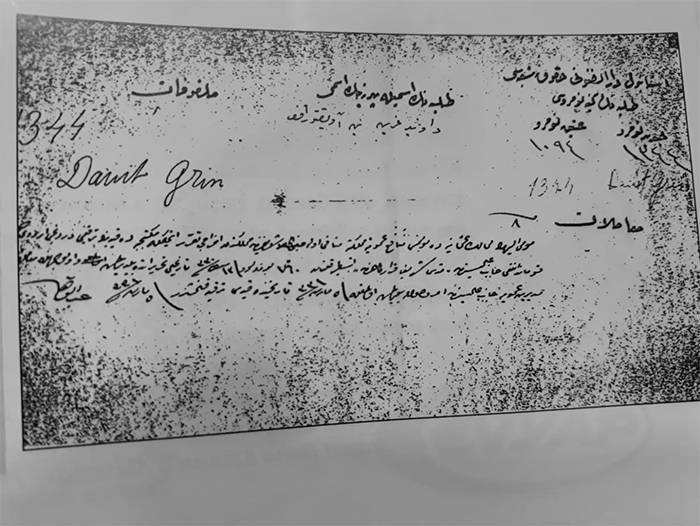

Initially, Ben Gurion ordered that Djemal Pasha’s decree not be printed or circulated in the Zionist press - but after he heard of Djemal Pasha’s actions he proceeded to disseminate it himself in newspapers, leading to the outbreak of a state of panic amongst the Jews due to Djmeal Pasha’s notorious reputation of severity with those who contravened the orders of the state or were proven to be traitors against it. Indeed, Djemal Pasha had hung Arab dissidents in Beirut and Damascus for contravening the orders of the state or on the accusation of cooperating with Ottoman enemies in other states, prompting Jewish fears that the same fate would befall the Zionist movement. A few days later, both Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi were arrested - and were threatened by the Ottoman commander Husain that they would be violently interrogated. Despite all this, the arrest and imprisonment of the Zionist leaders was not considered to be a major problem, as those imprisoned in official facilities had permission to visit gardens and meet their visitors; furthermore, the two leaders enjoyed a degree of immunity and respect as students of Istanbul University - and the saga ended with Djemal Pasha signing an order for their exile from Ottoman lands, on the condition that they never return to the country.

Subsequently, in his decision on Ben Gurion, the director of the Faculty of Arts in Istanbul University wrote: “When it became clear that Ben Gurion’s remaining inside the borders of the Ottoman state would cause harm to the general interests of the Empire, a decision to expel him outside the borders of the state and cancel his educational registration was taken; this decision was sent by the higher authorities in the fourth directorate of the army to the military administrative center in Holy Jerusalem with the date 12 Safar 1330 [Islamic calendar], and his educational registration was cancelled on the 5th of Azar 1331.” What this meant was that Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi were condemned by the Ottoman state, and that the Ottoman governor Djemal Pasha monitored the implementation of the decision - leaving the duo with no choice but to compulsorily leave the state. Nonetheless, they did not immediately surrender to the decision, and embarked upon what could be described as an appeals process; here, Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi both wrote a petition to the military commander of Jerusalem to deliver to Dhemal Pasha in order to cancel the order, with a portion of the petition appeal reading as follows:

“To his excellency the Pasha officer of the fourth army and head of the navy: we have been informed that we will be exiled from Ottoman lands on the charge of belonging to a secret gang that works against the interests of the Ottoman state, and we have been deprived of completing our education in Istanbul University. Furthermore, the activities that we undertook and the principles we defended are sufficient to drop the charges against us, for we were not part of any illegal organisation but were members of a Zionist group, Poale Zion, and this group like its other Jewish counterparts as it:

Does not operate outside the law

Publicly carries out its activities

Is not harmful to the interests of the state

As for our newspaper that has been expressing our ideas since five years ago: a copy is delivered every week to the [state] commissioners.

As for our activities, ideas and aspirations, [these] aim for the welfare of the Jews present in Palestine, which means that we are serving the interests of the Ottoman state. [Noting] that these Jews had left Russia eight years ago, and were subject to injustice there and became famous for their sorrowful stories. We came to this state to become subjects of it, and we love it since our childhood, because the treatment that Jews have found in it has been good, and can be considered an example of good treatment. We are not attached to Palestine only because we love it and because of religious bonds, but we are attached to the Ottoman state that opened all its doors to the Jews. We came to Istanbul to finish our studies, and we learnt Turkish and studied in the faculty of law. In other words, we have tied our lives and our futures to the Turkish state and Ottoman law. Seven months before our examinations ended - that is, when the war broke out - we volunteered to join the Turkish army at the military commander of Jerusalem to participate in defending our Ottoman brothers, but sadly we were met with refusal. You can ascertain yourselves that our ideas and actions were for the interest of the Ottoman state by following [reading] our newspaper.

If you still think us to be a secret group against the Ottoman state then the reason for that is your misunderstanding of us. We always feel that we are wronged and deprecated because of the threat of exile, and from this equation it became apparent to us that the Ottomans consider us to be foreigners. We also have a conviction that we have the right to be subjects [dependants] of the Ottomans. And if you consider what we did to be a sin and mistake then we urge you to punish us as Ottomans, and we are ready for any punishment you see fit however heavy it may be.”

This was the message of Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi: a crucial historical document in need of in-depth study, with all its contents and requests, and need to assess their credibility or otherwise. Could it have been truthful in its contents? Or was it a deception - a time-limited ruse?

In the event that it was truthful, and that Ben Gurion did not find a contradiction between belonging to a Zionist movement and encouraging its presence in Palestine on one hand, and being a dependent subject of the Ottomans on another, then the document would serve to demonstrate a special understanding by Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi of the Zionist movement at the time. These ideas require an in-depth and documents-based historical revision.

Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi had referred the Ottoman state - through the message directed at Djemal Pasha - to read their newspaper which Ben Gurion had been publishing for five years under the Ottoman state, and which he used to deliver a copy of to the responsible Ottoman officials. Considering the above reading at face value, it is apparent that Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi found in their newspaper evidence of the credibility of their statements and claims: that they wanted to be made Ottoman citizens, wanted to defend the Ottoman state, as well as the other various provisions which they had mentioned.

However, what ultimately took place in the actual history was that the military commander did not dare deliver this hand-written document to Djemal Pasha, choosing instead to post it. After a period of time passed, Ben-Zvi visited the first aide of Djemal Pasha, who met him and declared: “The first aide of Djemal Pasha informed me that he has ripped up your message and thrown it” - thus making clear that the exile order was still in operation. Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi would be imprisoned in Jaffa until such a time that a ship arrived to take them, before being arrested again on their way to Alexandria, as they were considered enemy subjects of the Ottomans. Meanwhile, Ben Gurion’s right to study law at the university ended with the end of the Ottoman state.

It is a sense of historical responsibility and duty that requires us to read and consider the position of Ben Gurion towards the Ottoman state: to study his documents and newspaper. It is furthermore undoubtedly the case that there is much information on the subject in Ottoman archives, including items that could dissect or refute the ideas mentioned in Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi’s message to Djemal Pasha. So too it is necessary to study the messages that Ben Gurion used to send to the Jews of the world, including a message that Ben Gurion published in a newspaper that he adopted after being exiled by Djemal Pasha, in which he declares:

“O dear sons of my country, O dear Jews: do not be deceived by the English and the French, who talk of democracy and equality in their countries; they are honest but only insofar as it pertains to themselves, they did not grant any equality in their colonies; there is one exception, it is the Ottoman Empire - all minorities live in it and enjoy equal rights without consideration of their religion and affiliation. So do not be fooled by the claims of the English and the French, and arm yourselves and form your own military, and join the Ottoman army, and defend Palestine against these invaders!!”

In conclusion, an article published in the weekly Turkish-Jewish Şalom newspaper discussing the legal system in the State of Israel - and how it derived much of its contents from the Ottoman justice code - poses a pertinent question: to what extent did the lawyers Ben Gurion and Ben-Zvi contribute an Ottoman style in building the legal structure of the State of Israel?

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!