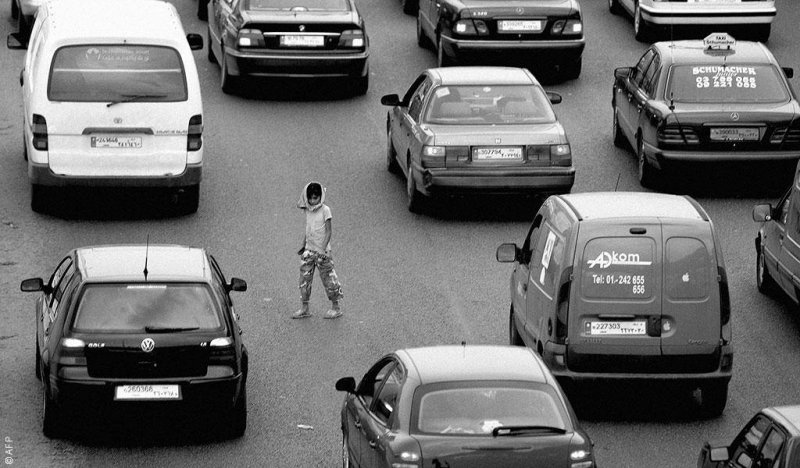

I’ve tried hard to forget him. The features on his face. The long conversations we had about his bated anticipation until he was reunited with his family, and the complaints about all the attempts to do so which had failed. In the end, he found death to be his quickest relief. This was the story of Rabie, the fourteen-year old boy who escaped a life of polishing shoes and sleeping on the pavements of Beirut. The boy who, only a few days ago, burnt himself to death during one of the lonely nights of his refugee camp. It was that day that I realised that my daily work with children wasn’t just because they were a marginalised segment of society, but because they were also potential victims-in-waiting. The first of September 2015 was the beginning which took me to where I am today. I didn’t know that the day that I entered the office of my new job would be the one that set in motion so many changes and stages of life that I would encounter in my future. Like all those working in the field of humanitarian work, I was exceedingly happy when I accepted the job offer – not least because the organisation I was working for was among the most important in the field regionally. The first of September was the date of my first meeting with the children who worked the streets of Beirut. How could I forget the moment I was told that I was to meet “Ahmed” in Al-Hamra Street to fill out his personal form? “He’s the most violent of the children in the area,” was the postscript at the bottom of this job request. My first field visit started with apprehension, for like anyone else who saw children working in the streets as sources of danger, law-breakers, gang members – pretty much everything but children – I was slightly worried about what I was to find. My first visit was the hardest. “Ahmed” surprised me with his strange behaviour and careful words. But he ended the interview in his Dara’a accent (Dara’a is a city in South Syria): “Can only you come? Because it’s clear that you’re [one of those] loving [women]”. I was surprised but pleased by his judgement, for he considered me pleasant from the first meeting. My visits to Al-Hamra street continued over a period of two and a half years. The children and guys working on the street who I saw every day soon became part of both my professional and personal life. But I observed a strange phenomenon amongst them, noticing that they treated each other with a degree of classism and regionalism. The children coming from Damascus and its environs believed that they were on a “higher level” to those from Dara’a and Deir al-Zor – to the extent that they would even condition us to divide them into separate groups during activities. The days passed and these children became an inseparable part of our daily lives, even after the project was completed and was passed onto another organisation. Among my duties in the project was providing support to the ‘street youth’. Being required to engage them in a set of activities, I had to participate in the 2016 Beirut Marathon. Me, the girl that hated waking up early on the weekend – walking from six in the morning across Beirut, trying my hardest to wake and prepare them! We got to the starting point, and I had to run with them – even though I couldn’t walk much at the time. So they decided – unanimously – to help me during the route: “Mohammed” proposed taking shifts (“We’ll run a bit and walk a bit and chill out”). “Taha” asked to use my phone so that he could take a picture of us during the marathon – claiming that my camera was better than his – and I admit I was slightly unsettled by the mischievous smile on his face. True to form, he said: “and if your groom calls we’ll tell him you’re safe with us”. These are the guys that we judge by virtue of their work and life patterns, only to discover after getting to know them up close that preconceptions can be the most dangerous mistake we make in our lives. That afternoon we shared laughs, and when we got tired of running, we switched roles. They were the ones who – being fitter than me when it came to sports, in their minds – gave me full attention. We shared many a conversation, about their desire to return to the alleys of the Yamouk refugee camp; about their hopes and fears for Syria, Lebanon and Palestine; about their work on the streets and their aspirations. “Fadi” told me about his dream to move to Germany to finish his education: “I want to become a doctor and treat people for free, for we are.” Do we know that these children and guys differ nothing from us, other than that their life circumstances forced them to be where they were? I’ll also tell you about “Mo’men”, the boy of many talents. The shy, bold, stubborn, and particularly affectionate “Mo’men”. One day, I was surprised to find his friend writing on her Facebook page, that Mo’men refused to tell me that he broke his hand so that I wouldn’t worry about him - for he knew that I loved him and cared about his situation. I met him two days later and he told me that he had a good excuse for not telling me, and asked me to listen: “Look now Cynthia, so this broken hand of mine, is it more important than Mohammed’s mother who needed to go to the hospital? Or Tha’er’s children who need to eat? Take care of them, here, my hand’s now fine.” A 15-year-old who lived in subhuman conditions and worked more than 14 hours a day every day. Asking me to take care of those he judged were in more need of help than him. These are the ‘children of the streets’: they aren’t thieves, and they aren’t criminals. There were many stories that I came across during my work on the project, few unfortunately of which we could consider a “success story.” Despair was the most-common feeling I experienced during the period of my work. At least that was until I visited Damascus with some friends, where we were walking in “Naseeb al-Bakry” street. I heard someone call my name. I didn’t give it much attention, for how could anyone here know my name, I thought. But I heard him repeating my name again and again, so I finally turned around to find “Adnan” – one of the project’s previous participants in Beirut. It was me, the person who adopted the strictest standards when it came to child protection, that couldn’t help but fall in love with him. It was perhaps the most beautiful thing that happened to me in my three years – finding “Adnan” in Damascus. He told me that he worked in a bakery nearby and gained experience from a professional training programme that he participated in when he was in Beirut. The “boss” treated him well and he was to become the owner of his very own bakery soon. I bid Adnan goodbye and left with him a joyous piece of my heart. It was the first time that I tasted the feeling of victory in three years. During three years of daily exposure to the children of the street and their families, I accumulated endless stories that I could recount – but the biggest challenge was the difficulty in dealing with this sector of society, and this project in particular: that is, it didn’t allow you to see its effectiveness. Only very few children stopped working on the streets after receiving support, and so I convinced myself to leave a small trace in their lives, better than remaining ‘neutral’ and on the sidelines. Perhaps it is us that should thank them for helping us change our outlook on marginalised groups in society, and perhaps it is us that should thank them for helping us challenge ourselves to give them the best we can. The children of the street and their relatives are families like yours: they are the victims of poverty and war; oppression and displacement; and the tyranny of the powerful over the weak. As for me, they constituted a lesson that I will never forget so long as I live – for they helped me far more than I was able to help them in return.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!