My first steps as I entered the New York Times’ Baghdad office in 2004 marked the beginning of a journalistic experience I had always dreamed and longed for. As time went by, it has proven to be a rich experience that taught me how to understand life better, after I met with people from all walks of life who have travelled across continents to write about me and my country.

The journalistic community in the compound we resided in was made up of two houses, surrounded by barbed wire, watch towers, and dozens of Iraqi guards. Such an unusual and interesting combination reflected the aftermath of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which toppled a regime that had, until then, remained firmly lodged in Iraqis’ minds as a destiny with no hope for salvation. There were high hopes for a better future in 2003, but what panned out was only worse.

I was quickly given the job, due to my good English language skills, as well as former jobs with several media agencies and temporary assignments that qualified me to become a valuable member of the newsroom and eventually take on its management in less than two months.

One of my main tasks was coordinating between the Iraqi and American teams when it came to the coverage of assignments and news monitoring. From there, my duties evolved into making decisions to prioritize news events, after the deteriorating security situation curbed the presence of Americans on the ground and news coverage became majorly dependent on Iraqis whose presence in scenes of events does not arouse suspicion.

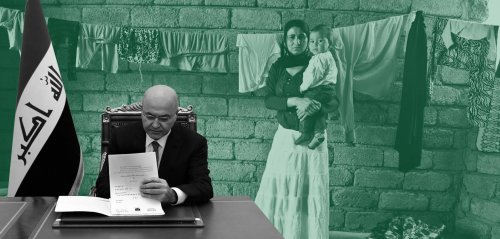

Two Different Societies

Sometimes work would go smoothly, while on other occasions, the vision of the teams would clash. Both work teams represented two completely different societies: an Eastern society cut off from the outside world for many years under stifling sanctions and an iron grip that viewed broadcast stations as an enemy to be feared; versus an open-minded western community that travelled across oceans to report to readers who couldn’t locate Iraq on a map before the invasion, let alone understand the complications of an endlessly unmoored society drowning in seclusion.

The American reporters who applied to cover Iraq’s war came from diverse backgrounds but were unified in their desire to see their names on the front page of the New York Times, one of the few papers placed daily on the US president’s desk. This hunger for fame did not leave much room to study and understand the society they found themselves in. There was little time in the fast-paced news operation, story deadlines were looming, and personal ambitions were the priority, not to mention the virtually non-existent cultural background about Iraq. Moreover, there was a condescending Orientalist attitude by some reporters towards a backward society that the United States is spending effort and money on to elevate to civilized standards.

Iraqis on the other hand, Iraqis perceived Americans at the beginning as the leading pioneers in civilization and sophistication, superior in everything, but they soon discovered that Americans are regular humans too. They express anger and jealousy, can be hit or miss, and deal with others in a superior manner. They sometimes even engage in gossip but also laugh and joke with Iraqis, occasionally offering them a helping hand.

The American reporters who applied to cover Iraq’s war came from diverse backgrounds but were unified in their desire to see their names on the front page of the New York Times. This hunger for fame left no room or desire to understand Iraq and its society

An Insult That Led To Discourse

During my time at the newspaper’s bureau, our daily articles would be sent to the main office in New York, where they would be proofread and edited, before making their way online. It was of particular interest to us to see what changes and revisions were made by the editor oversees, and how insights, quotes, and interviews were used during the editing process.

The lead story that day was by a young American journalist who had been working at the office for two years. Her interest was lengthy articles and in-depth exposés on Iraqi society and the effects of war. That day, her article had been on sectarian conflict and the growing social schism between Iraqi Sunnis and Shi’ites. I had gotten halfway through the article before I was brought to a halt by a phrase that jolted my very core. I turned towards my Iraqi colleagues - both Sunnis and Shi’ites - and called for their attention. As I read the statement out loud, I watched all their faces flush and morph in anger.

The journalist had met with an Iraqi woman to discuss the growing sectarian strife in Iraq. During their conversation, the woman relayed having witnessed a man at a local gas station throwing snide glances at a group of young men in line ahead of him. The young men were conversing in a specific dialect of colloquial Iraqi Arabic, that made it clear they hail from one of the poorer Shi’ite neighborhoods of Baghdad. As the young men tried to cut him in the line, the irked man said, “Those Shiites were servants. They wiped our shoes. Now they are going in front of us." Coming from an American mentality, the author must have seen this as stark evidence of the deep-rooted hatred among Sunni and Shi’ite Iraqis. It would be convenient, from an American perspective, to view this primordial animosity as the driving force behind the sectarian conflict in the country.

The writer wrapped up her ‘well-founded’ conclusion in a neat journalistic package and delivered it to the American reader - to rid his guilt and ease his conscience; thinking she had performed a thorough anthropological research that revealed the roots of the conflict using a passing conversation at a gas station. But to many Iraqis at least, this point of view is a ready-made parcel for some American journalists to confirm their preconceived biases and prejudices rather than search for the truth.

The American journalist wrapped up her ‘well-founded’ in a neat article with a conclusion drawn from a casual conversation at a gas station, convinced she documented anthropological research revealing the roots of the Sunni Shia conflict

The anger in the newsroom was palpable. Afterall, we were the ones helping, translating, providing references, and explaining local nuances to other journalists. We wrote and prepared the raw material needed for the articles that get posted to the website. Reporting such an un-whole image - a single voice exaggerated and amplified - is neither ethical nor professional. Any person from any prejudiced upbringing or background could spew racial and sectarian hate speech, and so making broad generalizations off them is both inaccurate and harmful.

I’m not writing out of rosy-eyed romanticism or denial of the sectarian tensions plaguing Iraq, but the journalist’s proposition goes against established facts of history and sociology. Sunni-Shi’ite relations in Iraq are largely constituted of amicable cohesion, marriage, and familial bonds – too complex to be portrayed as a relationship between a low-life shoe-cleaner and a powerful, conceited master. Our main concern at the newsroom was that this article would find its way to local Iraqi media, where it would agitate animosities and fuel the fire for real sectarian conflict at a time when killing on the basis of one’s ethnic identity was rampant. None of us wanted part of what would come should the article go public. Indignant outcries filled the office space. Someone placed the blame on the Iraqi who translated the man’s statement to the journalist, saying, “We need to be careful what we tell them. They’re either too dense or bigoted.” While others blamed the journalist herself, conjuring up previous incidents where she had gone out of her way to find statements that fit her preconceived interpretation of events.

Word of our indignation reached the American side, and the acting head of the American team at the time – one of the smartest, most tactful and thoughtful reporters who worked in the bureau - reached out to me, anxious to address claims about us Iraqis wanting to censor the content we receive for translation. I immediately assured him of our professional integrity, and that we would do no such thing, despite being angry about the callousness of the piece in question. Later, the article’s writer briskly walked up to my desk in the newsroom, angry and surly-faced, and said:

“Next time, I would prefer you say what you had to say to my face.”

“If I wanted to talk to you, I would have. I’m not afraid of anything.”

“What’s your problem?”

“Can you walk the streets of New York straining your ears for anti-Black or anti-Jew hate speech spewed by random strangers and offer it up as an exposé of racial or sectarian hatred in an article for the New York Times?”

“The situation is different here.”

“Why? Because there are restrictions and red lines in the US, but us Iraqis are fair game?”

“This conversation is leading us nowhere. Excuse me.”

And, thus, she walked back to her office at the other section of the complex, thinking she had just wasted her time trying to talk to a dimwitted Iraqi that doesn’t understand the specificities of proper journalistic conduct and is in denial of the sectarian hatred within his environment. I definitely wasn’t in denial. I was just convinced that the subject deserves more nuance than a curse word thrown by a random stranger at a gas station.

This same journalist had come to me earlier that summer to share an impression she had on one of her excursions. Having just arrived from an outdoor interview, she walked straight to my office, took off the headscarf she was donning for security concerns, and sighed deeply before saying, “You Iraqis are incredibly brave.”

To which I responded in surprise, “Why would you say that?”

“I was just on a visit to a young woman who lost her husband to an explosion a few months earlier. His sudden death left her with their 5 children whom she must feed and fend for all by herself. She’s going out every day to work and provide for them with no one’s help and carrying all this responsibility that fell upon her out of nowhere. If one of my parents had went through something like this, they would have killed themselves.”

The Baghdad office teams represented two completely different societies: an Eastern society cut off from the outside world for years… and an open-minded community that crossed oceans to report to readers who didn’t even know where Iraq was on a map

Beyond the Desert

There were times when we would pause at the reactions of Americans when they discover that there is more to Iraq than just barren deserts, palm trees, and women wearing the niqab (face-covering). One day in 2006, an American reporter that had just recently began working came to me with a piece of paper in her hand. She gave me the paper and said, “Do you know this name?” The paper had the name ‘Nazik al-Malaika’ written on it in English. I replied, “Of course I do.” The name belonged to the great poet that died that very day in Cairo. She then asked me, “Can you appoint someone from the Iraqi team to help me write her eulogy?” I said no, to which she replied with a surprised, “How come?” I then told her, “No one will work on this story but me.” She smiled and said, “What do you know about her?” I’m not sure why I then stood up from my desk to deliver an enthusiastic and lengthy spiel of the shy talent that singlehandedly produced torrents of fine Arab poetry, and who completed her masters in 1950s America to return to teach and deliver the world the finest free verse poetry, eventually taking her place as the most prestigious Arab poet of the 20th century.

“Can you summarize this for me in an email please?” The reporter asked me with apparent enthusiasm perhaps driven by my own passionate talk. We quickly worked on the specifics of her life, and I provided content that could interest the American reader. When asked to supply some sample of her poetry in English, I chose a segment from the poem “To Wash Their Shame Away” or “Ghaslan Lil-A’aar”. The primary challenge for me was, for the first time ever, I was not only to translate poetry but also that which belonged to the stature of Nazik al-Malaika herself. The journalist liked the poem, and the eulogy was published days later. On the day it was published, the reporter came into the newsroom, handed me a small envelope and left. Inside, I found a small card that said, “Thank you Ali for the poetry and thank you for introducing me to an Iraq I didn’t know.”

This compound did not only contain two houses, but also two worlds. Sometimes they came close enough to each other to merge, such as when the Iraqi football team won the 2007 AFC Asian Cup. It was the first joy that we felt following years of bloodshed and suffering. Our English bureau chief, a huge football fan, was seen that day jumping in joy among us Iraqis in the newsroom, yelling, “We won!” The American reporter tasked with covering this unique celebration that unified all Iraqis came up to us to ask about the team players and their denominations. I didn’t know, and neither did anyone else in the newsroom, to the puzzlement of the reporter. I told him we really do not have such knowledge about the football team; sure, we could guess from some names who might be Kurdish or Sunni or Shi’ite, but for the most part, we do not have an ethnic and sectarian map detailing the Iraqi team. I had to contact some friends and relatives to ask and verify, since names do not necessarily reveal a person’s sect. As I inquired, I would apologetically explain that this was to clarify to American readers that Iraqis can play and win as a unified team as they once were, and that their history did not begin with sectarian violence.

We also came together in moments of sorrow, when militias assassinated our correspondent Fakher Haidar in the city of Basra, as well as our younger colleague in the Baghdad newsroom Khaled Hassan two years later. All of us, Americans and Iraqis, gathered on the day of Khalid’s assassination in a moment of silent mourning that witnessed plenty of shed tears and shared grief.

Other times, the wide chasm between us would remind us that we are working with people that came from overseas, and that blue and brown eyes may not see the same even if both sights were set on the same thing.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!