I learned about Islamic burial rites from Wikipedia the day after my dad died in 2017. I was suddenly confronting rituals I had never observed before — mourning customs that honored him through a faith I had never practiced traditionally.

I was certain my dad wanted to be cremated and buried in Lebanon, the country he loved with every fiber of his being. But, I learned, cremation in Islam is forbidden because the body is seen as sacred. Islamic burials are to be simple and natural; we came from the earth and therefore should return to it.

I can remember the dust in the air as the sunlight shined through the windows while I sobbed in my bed. I didn’t eat for two days. I had to figure out how to bury him in Canada, where he had lived for over 30 years after his family fled the Lebanese Civil War. But he never considered Canada his home — it was always Lebanon.

I was certain my dad wanted to be cremated and buried in Lebanon, the country he loved with every fiber of his being. But, I learned, cremation in Islam is forbidden because the body is seen as sacred. Islamic burials are to be simple and natural; we came from the earth and therefore should return to it.

I don’t recall my father ever observing Ramadan, but my mother tells me that he loved Christmas, especially after I was born. We celebrated with a tree, decorations, and presents but without the midnight mass or nativity scene.

Although raised by a Lebanese Muslim father and a Filipina Catholic mother, I grew up secular. When I was in elementary school, I remember going to the local mosque in Richmond, British Columbia for Arabic — or maybe it was Qur’an — class. The mosque was located in a primarily East Asian city and locals referred to it as “the highway to heaven,” because of all the temples and mosques along that stretch. I only ever returned to the same mosque in Richmond, decades later, to bury my father.

Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.

Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.

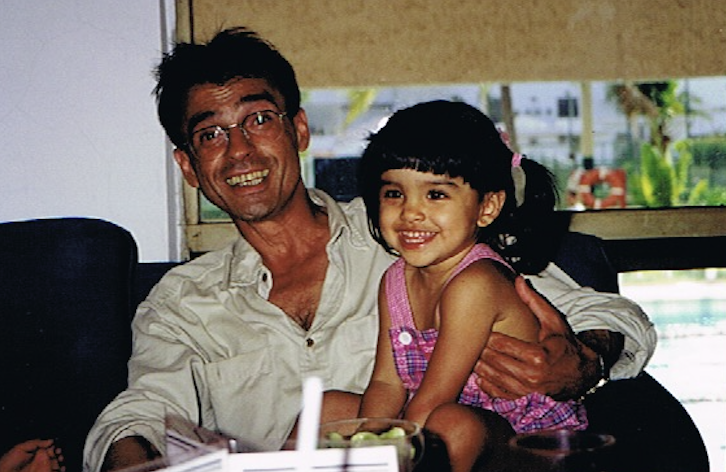

Karla and her father, Anwar. (Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.)

Inside a small British Columbia Muslim Association office, my mother, uncle, his wife, and I sat around a boardroom table. During the orientation, I had to solemnly swear that my father was a Sunni Muslim. This was also my first time discovering that there were other Islamic sects. Inside a brochure of all the burial packages, services, and pricing, there was a sheet with the Association’s guidelines and policies on headstone designs, and half a page of rules and regulations dedicated to flower arrangements.

My mother was mourning her life partner, the father of her only child, whose hair was dyed a vibrant pink that day. I was barely 20-years-old, but I was responsible for figuring out where he would be buried. My body was in the room, speaking to the funeral director, but my mind was elsewhere, like a lagging computer stuck at the loading bar.

I was used to handling complex situations for my father, who was a quadriplegic since I was three. In hospital settings, I supported him, especially when he was being mistreated or ignored in Canada’s racist healthcare system. I was able-bodied and I knew the language to make them take him seriously. My father was tough and outspoken, despite his disability, which empowered me to speak up. But this time I was all alone. There were people around me but I was alone.

I went ahead with the Islamic burial, per the insistence of his more observant siblings, because I didn’t want my dad to be alone, wherever he went.

Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.

Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.

For Eid, I’ll be making my dad’s favourites — tabbouleh, fatayer sabanekh, bamye, and loubieh bi zeit. (Photo courtesy of Karla Jubaily.)

One day, years after my father passed, somebody told me that in Islam, when you do a good deed on behalf of someone who has passed, angels are sent to them. Since then, every Ramadan, I have donated my time and money to mutual aid, fed others, or offered my kindness — in hopes that angels will meet my dad wherever he is now. This was my annual portal to reaching him.

“Ramadan is one of the few times a year when our whole extended family, from my grandmother’s and grandfather’s side, comes together. For years, I missed the feeling of Ramadan and community while in Vancouver. And now with my grandmother gone, I’m even more determined to keep this tradition alive and cook foods she used to make.”

I don’t remember how I met Mahy, but when I asked her, she remembered right away. It was in 2019; our friend Ashwini introduced us when we were still undergraduate students at the University of British Columbia. I was yelling at a counter-protestor during a pro-democracy Hong Kong action.

Over the years, I found a community of friends who were also on their own spiritual journeys. In the absence of our loved ones and our distance from families abroad, we come together, hosting iftars, consulting with each other about the nuanced ways we are observing Ramadan, including fasting but beyond it, too.

I saw how Mahy’s loss strengthened her commitment to Ramadan, motivated by the blessings that her observance would reach her grandma, and how the grief encouraged her to honour her grandma during Ramadan. Grief can be isolating, but these new traditions we shared were rooted in both remembrance and renewal.

Over the years, I found a community of friends who were also on their own spiritual journeys. In the absence of our loved ones and our distance from families abroad, we come together, hosting iftars, consulting with each other about the nuanced ways we are observing Ramadan, including fasting but beyond it, too.

Food was taken seriously in my family. My great-grandfather, my grandmother’s father, first owned a patisserie in downtown Beirut and then a Lebanese restaurant in Haifa, which closed down due to the occupation. My grandfather was a butcher when they immigrated to Canada, so a lot of our shared family recipes were meat-based. When I watch my friends' faces as they eat the Lebanese dishes I prepared, I wonder if my dad used to have the same feeling watching me eat the food that reminded him of his home.

Mahy’s fondest memory of her grandmother was when she was young and couldn’t fast yet, so when it came time for her family to break their fast, Mahy’s grandmother would make her a bowl of fava and bean sprout soup to eat while watching cartoons on the couch.

“This soup usually takes about a week to make so it was a labour of love. So I try to make more difficult dishes in Ramadan to pass on that labour of love.”

For Tuleen, Ramadan is a month for giving. Her fondest memories from growing up in Amman and observing Ramadan with family were the pre-iftar activities where she would join her late father in picking up a rotisserie chicken, laban, and juice, some of which they shared with neighbours and their doorman.

“He was funny, handsome,” she joked, in typical Tuleen fashion, “and generous with his time and energy, which is what I’m trying to do now.”

I met Tuleen through a network of local Arab and Persian arts and culture community members — even though neither of us are artists. This Ramadan will be the first without her dad. She plans on trying to make Qamar al-Din, the juice she most remembers, sold by the neighbor's kids at their stands back home during Ramadan.

“I’m realizing all my traditions, or most, are either around giving or food.”

Not many of my friends have been to Lebanon, or met my dad, so my hope is that through sharing his favourite dishes, they will get a sense of who he was and what he continues to mean to me.

This Ramadan, I challenged myself to fast for the first time. During the month’s first iftar, which Mahy hosted, and on our third year of the tradition, I prepared fatayer sabanekh from scratch, a childhood favorite of mine, and lentils.

I also decided to take on hosting Eid at my house this year. My mother told me that my dad loved hosting and cooking back in the day to showcase traditional Lebanese cuisine to their friends. He was known among their friends to be an expert at barbecuing with charcoal — a unique skill to possess in Vancouver.

For Eid, I’ll be making my dad’s favourites — tabbouleh, fatayer sabanekh, bamye, and loubieh bi zeit. When I was younger, these dishes felt mundane, they were simply meals we ate at home, but now they’re special, like a treat. Not many of my friends have been to Lebanon, or met my dad, so my hope is that through sharing his favourite dishes, they will get a sense of who he was and what he continues to mean to me.

This year, I only asked invitees that if they wish to bring a dish, it should be one that reminds them of someone they miss, whether they’ve passed or just far away.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!