My love story with the Arabic language is the story of missed appointments, twists and turns, lost years postponing our inevitable meeting. Like any proper love story, our paths kept crossing. I was always intrigued and naturally drawn to its melody, its calligraphy, and above all, its music, but never ready to commit seriously and long enough to study it. Later, I always told myself, with a sort of agenda in mind. First Spanish and Russian, then time will come for Arabic.

1995, seven year old French me is entering second grade. I hate the brown velvet pants and the loafers that my mother makes me wear, the posh headband being the cherry on top. School is quite boring to me and my nanny picks me up every day at 4.30 PM. First, we fight over homework then, she teaches me how to count in Arabic. Sometimes, we listen to the French oriental radio channel and she brings home made delicious gazelle horns filled with almonds and sprinkled with dusted sugar. I love the photos of her sisters seven-day wedding back in Morocco, as well as the taste of the Ras el hanut in the potatoes.

Love definitely feels better in Arabic. The daily “sabah el yasmin” and “sabah el assal” of my friends make my day sweeter. Arabic is the language of a very touching community, full of affection and love, which welcomes the present and knows too well the unbearable fragility of life

Thanks to Mahmoud Darwish, Elise Diana has become an Arabist. Isn’t she right when she says: Don’t you think that the intonation of the word “jerah” is closer to the reality of the wound than its English translation? On the beauty of the Arabic language…

2002, I enter high school. Arabic is available as an option, very rare for a medium size town in France, but my heart is already taken by Russian language which I started a year earlier: I fell in love with the letters and the intonation of the language.

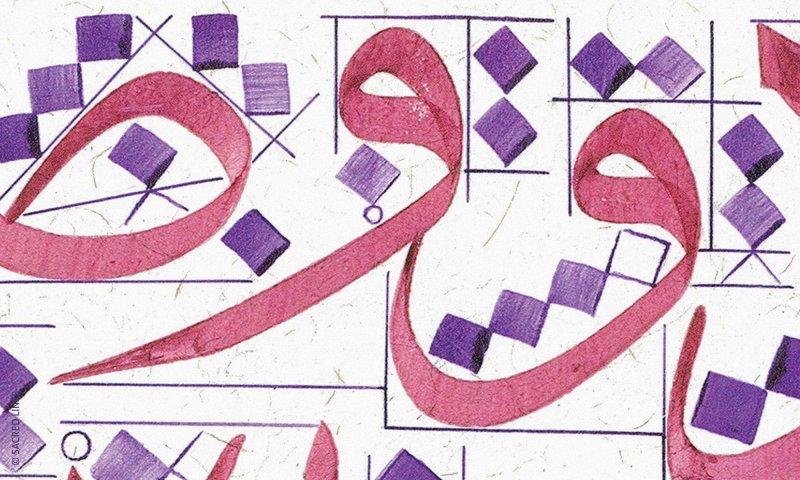

2008, I am a young student at Bordeaux University. I register for a three-month intensive course in classical Arabic. We learn the letters and listen to a live recording of Oum Kalthoum. The professor explains the meaning of “ya leil ya ayn” and the history of tarab. We listen to artificial conversations between Karim and Jamal, the protagonists of our book, while they sit in a café and order narghile. Arabic grammar is overwhelming, even if I enjoy its poetic concepts such as sun and moon letters. I then enrol the same year in a private course, but abandon it once again. It feels as if I haven't yet found the melody that I am longing for.

Life goes on, and in 2014, after a distressing break-up, I am searching for a roommate in Paris. One evening, Ryan shows up on my door, wearing a houndstooth coat, arriving from Lebanon to study in Sciences-Po. I realise I have absolutely no knowledge of the Middle East whatsoever, and I can’t even identify and conceptualise the language that she speaks when she fights with her mother over the phone. It is so far from Arabic dialects I heard before, mostly Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan! I love its melody, the sophistication of her tone, the attitude and physical expressions that come with it and on a cold autumn night, I learn my first words: “tree” and “red”. The next summer, I am sitting in a plane going to Beirut and I get a first emotional shock when looking at the city from the plane; why does it feel so familiar, as if I was finally returning to where I belong? During this trip, I am devouring everything around me, whether it is the knaffeh I am tasting at timeless Hallab’s restaurant in Trablos, the sunset over the sea, the cedar forest, the figs on our way to the mountain, the old stones of Beirut. My curiosity for this country has no limit, nor does my motivation to learn the dialect. The first day, I set up my own learning method: I will take note on my phone of every new word and will keep on taking notes until reaching C1.

After this trip, the perseverance acquired to learn Arabic will never leave me. Back in Paris, I join a Lebanese dialect class at the Institute for Mediterranean Studies, and I keep writing down words and listening to music. I then visit Palestine and fall in love with El Khalil and its moving mosque housing Ibrahim’s tomb, the liturgical chants in Arabic in Bethlehem’s cathedral, the sunny hills of the Palestinian countryside through the windows of the minivan, the animated streets of Ramallah. I glean words along my way, and my notes tell a great deal about what my eyes are witnessing: “krum”, “tatbi3”, “ehtilal”, “moustawtinin”. I go back to Lebanon and see the bell towers of the churches under the snow, the souk of Trablos, the lowlands of the Bekaa valley. Finally, I move to Berlin for three years and learn about Syria through thousands of stories of the Syrian diaspora and soon know Sham and Aleppo like the back of my hand without ever setting foot there.

Now I could write for hours about Levantine dialect. I love the richness and variety of it, the melancholy of long vowels, how each region has its own specificities, how Northern Syria talks with the “Q” when Palestinians use the sound “G” and Lebanese people make a small pause. Shouam have this very melodic way of pronouncing any sentence by emphasizing the last syllabus when Ghazaouis have a pronunciation as rough as their modern history. People from Swaida make the language sing. So do Arabic speaking Kurds of Syria. I love how this language travels in space, between its many provinces, but as well in time: many words are still borrowed from French and show the influence that the French occupation had in Syria and Lebanon. Interesting enough, both countries didn’t pick up the same words and also adapted them to Arabic language: Lebanese people wear “pantouflat” and swim in “piscines”. They eat cakes with “fraises”. Syrian women wear “rouge”, “soutiens” and take care of their nails by doing “manicures”. Contemporary Levantine dialect is now integrating new words under the influence of globalization: most words related to technologies are derived from English.

Many words are phonesthemic, which gives the language a very concrete and performative characteristic: when you “oueshouesh”, you can already hear the whisper that you are talking about. Pronouncing the word “hawa” already makes you feel the wind. “Qass” sounds like the blade slicing through the air. Talking in Arabic turns you irremediably into a poet and a magician.

Learning Arabic also made me reflect on my own mother tongue. By reading articles on the importance of Arabic language by linguist Jean Pruvost, I realised that Arabic is the third source of influence in French language. This made me think about our relation towards the language as part of our identity; Arabic became so natural to me, it shaped my vision of the world, and my life to a certain extent. It brought me close to a number of people I might have never met. It gave me the chance to have someone to tell the many precise words that can describe my feelings, from “hob” to “ashq”. Today I can assert that love definitely feels better in Arabic. The daily “sabahs el yasmin” and “sabahs el assal” of my friends make my day sweeter, even when they come in animated gifs with glittering roses and cups of coffee! It is the language of a very touching community, full of affection and love, which welcomes the present time and knows too well the unbearable fragility of life.

With time, as I started glimpsing the complexity of being the descendants of such a majestic and heavy heritage at the same time, I became more receptive to classical Arabic thanks to Mahmoud Darwish and his words, both limpid and powerful about freedom and the wound of the occupation. He made me acknowledge the role of the artists and poets; to tell the stories of those who are oppressed and suffering, and how those word can carry a political message. He helped me be perseverant in my fights and defend my convictions. By the way, don’t you think that the intonation of the word “jerah” is closer to the reality of the wound than its English translation?

I also felt the purity of Quran and Adhan, the emotions and the peace that it brings to the soul. It seems that time also came for Fusha, which I started studying last week with my friend Karim from Gaza.

I will never be able to fully understand the complexity of feelings that Arabs have in their heart, the frustration, the anger, the fears, the wounds, the hopes and the immense love they have for their countries and their families, and their culture. However, every day of my life, I am proud and grateful to be a small witness of the great story of the Arabic language and those who use “el lougha el dad”; I admire their courage, and their unconditional love for life, and my only wish is that we keep dreaming and protesting together, because we have that which makes life worth living, and we love life when we find a way to it”.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!